Process Commodities: Modern Aesthetics and the Autonomy Imperative

Rembrandt, Sheet of Studies: Head of the Artist, a Beggar Couple, Heads of an Old Man and Old Woman, etc., 1632.

On a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago last spring, I encountered a small Rembrandt etching titled Sheet of Studies. The piece is comprised of a suite of black and white figures: a self-portrait, a hooded face, two elderly folks with walking sticks, some other indefinite mess of lines. The contents are variously oriented and apparently unfinished; the old folks walk on ground parallel to the paper’s right edge, while Rembrandt’s head is missing a hat. They are also, these figures, unrelated to each other—except, I suppose, for the fact that their referents all left an impression on the same Dutch artist almost 400 years ago.

The wall text was less concerned with the figures themselves than with the question of why Rembrandt had chosen to make the print at all: “Rembrandt treated a small copper plate like a page from a sketchbook,” it claimed.

Wielding the etching needle like a pen, he jotted down unrelated sketches on the plate, turning it as he abandoned one idea and moved on to the next […] Rembrandt boldly decided to share its results with the public through the medium of print.

Was this in fact what had called my attention? I looked back over at Rembrandt’s face. I thought of all the effort he took just to print out some doodles, the mere stuff of his ideas. In a notebook I wrote down my own impressions with the transient but familiar and also absurd conviction that writing such things was my purpose in life.

I’ve since been thinking about Rembrandt alongside a rather standard Marxist precept, here issued by György Lukács: “To leave empirical reality behind can only mean that the objects of the empirical world are to be understood as the aspects of a totality, as the aspects of a total social situation caught up in the process of historical change.” To be sure, for Lukács, the standpoint of the proletariat differed in some crucial respects from that of a well-patronized Renaissance artist. But the passage can still help us appreciate Sheet of Studies for summoning the sense in which an artwork, like any commodity, is not an isolated absolute but a component of a specific historical process. Indeed, Sheet of Studies emerged out of Rembrandt’s “first Amsterdam period,” a phase of his career in which his reputation grew rapidly. If such growth represents conditions under which an artist might learn to unify knowledge of his market with knowledge of himself, we might want to venture that Sheet of Studies represents the aspiration against its fate as a commodity. Indeed, it is as though Rembrandt’s point in sketching on a copper plate was to work process itself into the ostensible stability of print. In Rembrandt, then, we find the sketch functioning as a particular expressive modality—one invested with the hope or fantasy of autonomy from the mounting pressures of commodification. And yet it should be equally apparent that what makes the sketch’s autonomy fantastical is the reciprocal sense in which formalizing and circulating itself as the process of its production reconstitutes its process as a commodity—indeed, as the commodification of the resistance to the commodity’s reification.

Surely this problem will be familiar to readers of Genealogies of Modernity. On the one hand, it is an irony central to theories of modernity in general. If the processes that are commonly said to characterize modernity (e.g., industrialization, rationalization, bureaucratization, and, in turn, frantic and equivocal forms of aestheticization) are those that reflect the commodity form’s total dominion over social reality, they are also those that fuel the desire for process as a holdover of autonomy. The problem, to reiterate, is that the sketch is marketable precisely because it inspires for its consumers virtues we want desperately to understand as untethered from the market: contingency, the provisional, and, above all, authenticity. Put this way, the problem may also be familiar to readers of this publication by virtue of the fact that such readers are indelibly tied up in a popular economy of cultural production (that is, theories of the modern) for which the sketch’s—or, more generally, process’s—ostensible authenticity remains essential. Here one might think of any number of recent products whose value is tied up in their record of their making: NFTs; method actors; or the para-social transparency of platforms, like Patreon and OnlyFans.

Indeed, we can see throughout the modern history of capitalism how the exchange value of process has grown to reflect an increasingly fanciful ideal of subjectivity—the ideal, that is, of being yourself. It may even help to think of modernism as the name for this ideal’s last gasp (modernism being what we generally think of as an experimental movement in formal aesthetics, representing a kind of cultural existentialism in response to the sedimentation of modernity’s key features: industrialization, corporate autonomy, scientific advancement, the primacy of the middle class, etc.). We can trace a brief history of this imperative of authenticity and the recourse it identifies in process forms by a brief genealogy of some exemplary modernists, like Baudelaire, Freud, Breton, and Adorno.

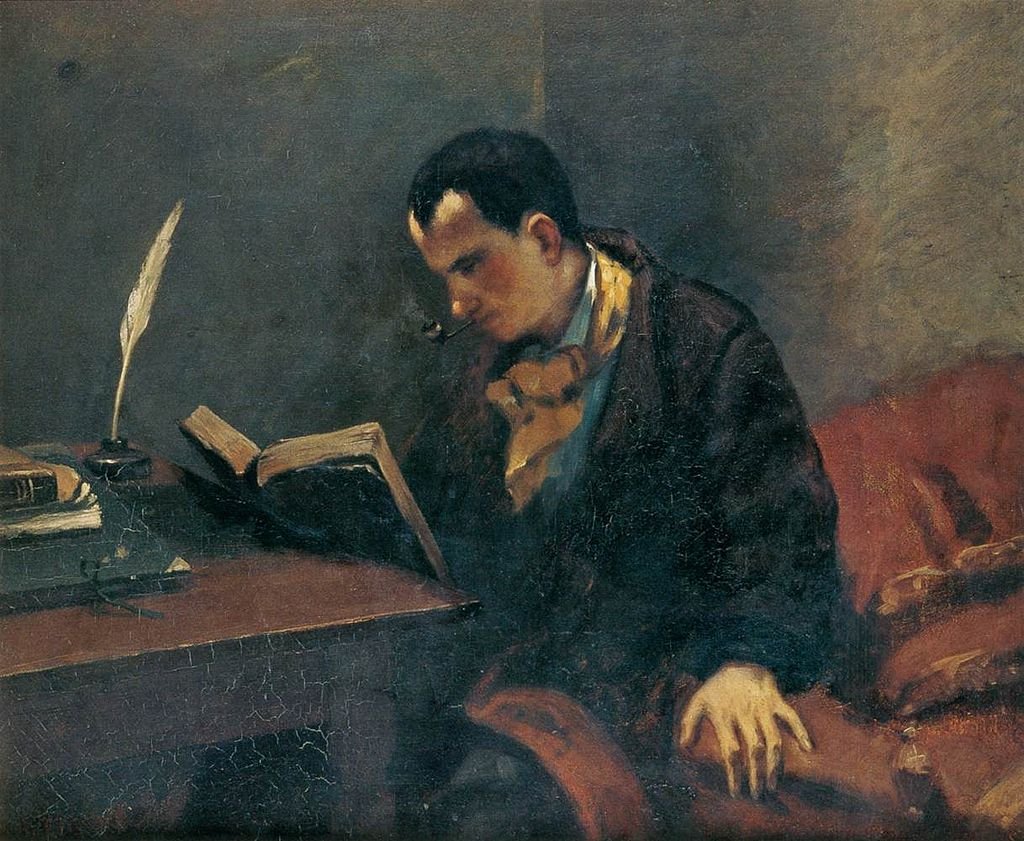

Gustave Courbet, Portrait of Baudelaire, c. 1848

In The Painter of Modern Life (1863), Baudelaire celebrated what he called the “sketch of manners,” an aesthetics of “darting” and “skirmishing” and “splashing” and “whipping […] in a ferment of violent activity,” which he argued could capture the pace of industrial modernity in a manner that also preserved for the bourgeois consumer the timelessness of classical beauty that consisted of a historicizing of the present. Psychoanalysis soon gave the matter a sheen of empiricism. Freud brought the ideal of authenticity to a concentrated study of the modern subject as a kind of mechanism. In “A Note upon ‘The Mystic Writing Pad’” (1925), he theorized a notetaking apparatus that could mimic human perceptual structures—that “mystic” relation that exists between conscious memory and unconscious desire. His goal was not only to analogize the mind as a complex of “receptive surface[s]” but also to expose the disciplinary faculties of internalized society: what Marx in The German Ideology characterized as the ability of the ruling class “to present its interest as the common interest of all the members of society […] expressed in ideal form: […] the form of universality.” Surrealism then came to represent the autonomy imperative’s most legible expression in the history of aesthetics. Indeed, in his “Surrealist Manifesto,” Andre Breton argued that the movement was realized “[o]n the basis of [Freud’s] discoveries” of “a part of our mental world,” which “under the pretense of civilization and progress” had been particularly abandoned in bourgeois forms of cultural production. If surrealism was, for Breton, the manifestation of “[p]sychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express […] the actual functioning of thought,” Freud’s work on the unconscious afforded modernism “the means of which the human explorer will be able to carry his investigations much further, authorized as he will henceforth be not to confine himself solely to the most summary realities.”

By the second world war, however, Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1951) seemed to creak under the implausibility of modernism’s autonomy from the market logic’s chokehold on human social life. Even the speculative possibilities of recent philosophy, wrote Adorno, had become “an appendage of the process of material production, without autonomy or substance of its own.” An unwieldy sequence of aphorisms written from his exile in California during and after the war, Minima Moralia gave form to Adorno’s dimming but once luminous faith in modernism as a final holdout of autonomy under capitalism. Indeed, Minima Moralia seems constantly to grieve its purpose—to “remonstrate against [the system’s] claim to totality”—as already subsumed by that system and as legitimating its claim. He cautioned that:

Subjective reflection, even if critically alerted to itself, has something sentimental and anachronistic about it […] Fidelity to one’s own state of consciousness and experience is forever in temptation of lapsing into infidelity, by denying the insight that transcends the individual and calls his substance by its name.

Now this essay—this awful sentence!—indulges an impulse to lead with subjective reflection, with process, in an effort to know it as a problem, even if not to redress it. Why? For one thing, I suppose, it serves as a kind of testimony to the corrosive effects the supremacy of the commodity form must necessarily have on even the theoretical privacy of consciousness. My life-affirming notes on Rembrandt were, of course, bound up in the tension I’d come to find Rembrandt evincing: between what I wanted to believe was the freely chosen preference I had for recording my life by hand and the heteronomous (or, per Adorno, sentimental) sense of the affective function my notetaking served. Here I was, a graduate student, communing with art at a “capital-I” Institute. I was, by all accounts, producing nothing—which is to say I was most valuable, since by producing nothing I was reifying the illusion of a possible freedom from the market. Indeed, despite my best wishes—and, I expect, those of many who read this publication—it is most unlikely that the commodification of autonomy is a problem resolvable by thinking especially hard about it. But I suppose the question remains whether it ought to be—whether there is value, solace, possibility, or at least something pretty in the notion of a system that must incorporate its contradictions precisely because it cannot hide them.

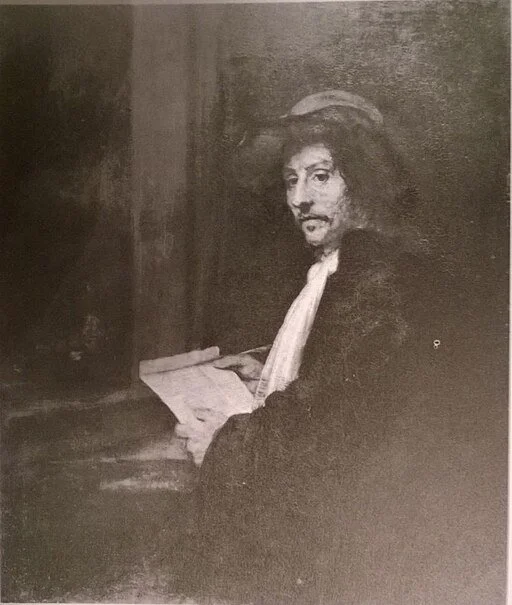

Rembrandt, Portrait of a Man with a Letter, 1658