The Return of Enchantment: Relational Reality at the Edge of Modernity

We live in a moment when the world feels both illuminated and dimmed. Our sciences see deeper than ever into matter and mind—charting subatomic fields, tracing neural circuits, and mapping ecosystems with exquisite precision; yet the more we illuminate, the more an absence appears at the center. Mastery has grown, but meaning has thinned, and we are left with a feeling of disenchantment. Beneath the noise of data, a quiet longing spreads, not simply the desire to know, but the desire to participate and to belong. We ache to sense that reality is something we can converse with, that it carries significance, and that understanding is a form of communion rather than an act of conquest.

This longing is not a kind of premodern nostalgia, nor is it generated by the sciences themselves. Yet it is striking that the very disciplines most shaped by modernity—physics, neuroscience, and ecology—are uncovering patterns and structures that converge with this desire. These disciplines represent modernity’s most ambitious projects: physics in its attempt to reduce the cosmos to fundamental particles and laws, neuroscience in its aspiration to map mind onto mechanism, and ecology in its effort to model life as systems of competition and control. What these modern scientific projects unexpectedly revealed, however, was that the cosmos is relational at its core. Across these fields a new sensibility is taking shape: an intuition that truth may be found not by reducing things to their smallest parts but by recovering the patterns of relationship that make the world intelligible. The desire for belonging and connection is not merely psychological but increasingly resonates with how reality itself is structured. What earlier ages described as communion or participation reappears in a new vocabulary of entanglement, interdependence, embodiment, and emergence. The terms differ between disciplines, but the underlying insight is familiar: the world is not a collection of discrete objects but a web of relationships, a reality that becomes understandable only through forms of participation. In what follows, I consider how the Catholic tradition can illuminate the meaning within such a cosmos.

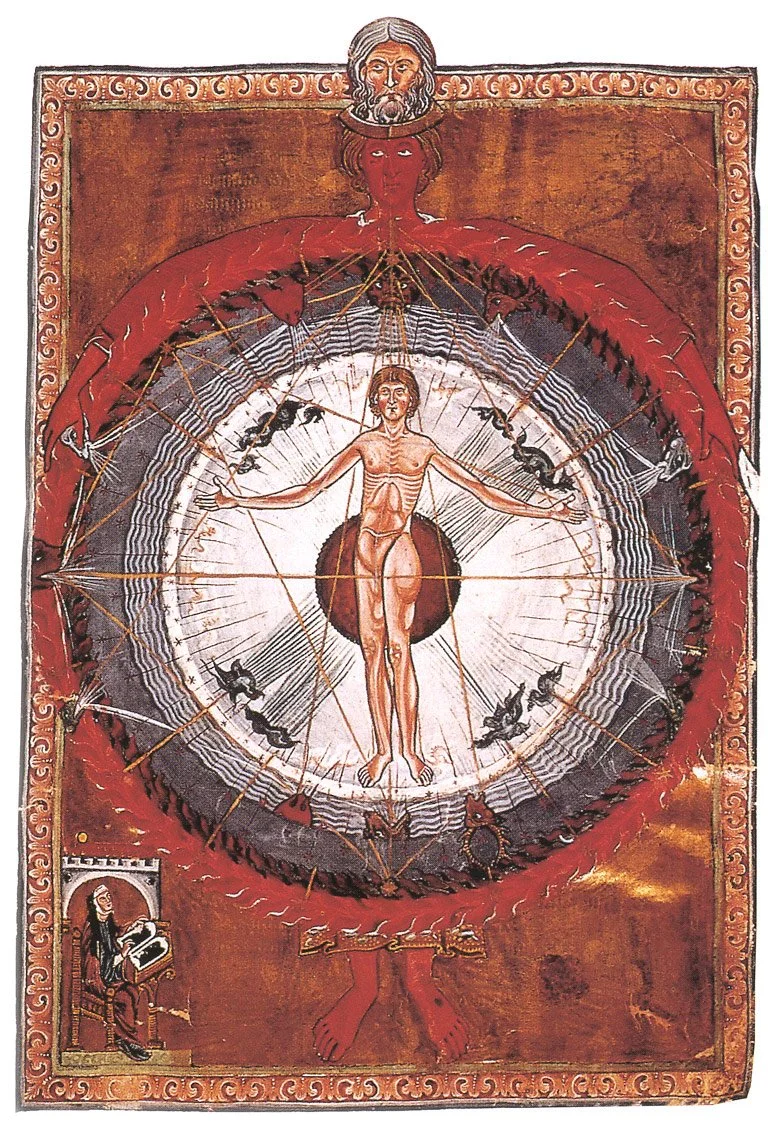

Hildegard of Bingen, The Universal Man (Anthropos), c. 1230.

The path to here has been long. Modernity imagined the universe as a machine governed by impersonal laws, with the human mind positioned as a detached spectator. Postmodernity then dismantled modernity’s grand claims, exposing their hidden power and shaking confidence in universal meaning. Its critiques were necessary, yet in its aftermath was fragmentation without renewal. Moreover, the desire for coherence—without naïveté or authoritarian certainty—did not vanish. It simply required better tools to reveal itself, and those tools are beginning to appear.

In physics, the deeper we probe, the less the universe resembles a collection of discrete objects and the more it appears as a web of interactions: quantum systems exhibit properties only in relation to other systems; many philosophers argue that particles are best understood as nodes within relational structures rather than independent objects; symmetry principles show that the fundamental laws of nature arise from relationality rather than absolute quantities; and entangled states reveal how classical notions of distance can lose their meaning. In ecology, life is no longer imagined as solitary struggle but as collaboration, where trees exchange nutrients through fungal networks, species co-evolve in mutual dependence, and systems survive and thrive through balance and reciprocity. And in cognitive science, the mind is increasingly understood as enactive—not a passive recorder of the world but a participant whose very perception arises through embodied engagement. These developments vary in method and domain, yet they gesture toward the same deeper intuition: that reality is structured by relationship, nothing exists in isolation, and coherence arises not from competing parts but from the bonds that hold them together. This emerging horizon, sometimes described as transmodernism (a form of post-postmodernism), is marked by the conviction that truth is relational, knowledge is participatory, and meaning arises through the integration of reason, embodiment, and reverence.

Within this realization, science and religion, once separated by modernity, begin to glimpse each other again. This is not because science is drifting toward religion, and not because religion needs scientific validation, but because both are encountering the same horizon from different directions. In the Christian case, this consonance becomes particularly striking. A relational cosmos is not foreign to Christian thought; it is its native language. It is the life of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the divine communion in which creation lives and moves. More broadly, Christianity has long understood reality not as a collection of detached entities but as a communion of relationships grounded in divine life. The point here is not an argument for the existence of God—whether via fine-tuning or other rational proofs—but a recognition that the relational patterns disclosed by the sciences echo, at a structural level, the Christian vision of reality. The emerging scientific worldview does not become Christian, yet it renders the Christian imagination newly intelligible in its underlying logic. Christianity, in turn, gives this structure depth, purpose, and direction.

Different Christian traditions articulate this relational vision in different forms. The Catholic tradition in particular has preserved a remarkably integrated account of relational being: the world as sacrament, creation as meaningful, knowledge through participation, and the divine Logos as the ground of meaning and coherence. These are not metaphors. They are claims about what reality fundamentally is. When the Gospel of John opens with the phrase “In the beginning was the Word,” it describes not the origin of doctrine but the architecture of existence. The world is intelligible because it is spoken into being, and it is relational because it emerges from the divine communion that gives it life.

Image generated by OpenArt.AI with the prompt: “Envision a softly luminous cosmic web stretching infinitely across the canvas, swirling with intricate biological patterns that resemble neurons and roots… [etc.].”

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit writing in the mid-twentieth century, saw a similar relational coherence in his scientific and theological work. He did not treat evolution as a ladder of improvement but as an act of becoming: matter capable of generating consciousness and consciousness capable of awakening into love. His point was not biological directionality, which Darwin rightly treats as contingent, but the deeper pattern that relational beings tend toward greater complexity, interiority, and connection. One need not unfurl his entire system to notice the conceptual echo with physics, ecology or neuroscience. The more that contemporary sciences illuminate relationality, the more Teilhard’s intuition feels less like poetry and more like a genuine insight into the nature of things: that, in our relational cosmos, creation tends toward deeper communion. As the sciences uncover how intricately the world is woven, Christian spirituality teaches how to inhabit that woven reality as meaningful. Their explanations differ, but they share a grammar—relationship, participation, communion—that allows their dialogue to move beyond polite comparison toward genuine mutual illumination.

Yet Christianity is not only a metaphysics. It is a way of perceiving and living within this interconnected reality. A sacramental worldview cannot simply be asserted; it must be learned, practiced, and deepened through disciplines that teach the heart how to attend and the mind how to dwell. Christian spirituality therefore becomes unexpectedly timely. Catholic and monastic traditions have long developed practices that train precisely the kind of perception that relational epistemology requires. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola teach discernment as the practice of attending closely to the movements of one’s inner life (to memories, desires, and emotions) as places where God’s presence and guidance may be recognized. Carmelite and apophatic traditions guide the soul into silence, where the divine is encountered beyond concept and image. Sacramental worship teaches that the material world is not a barrier to divine life but its bearer. These traditions do not oppose reason; they deepen and direct it. They cultivate forms of attention, stillness, receptivity, and discernment that allow a person to perceive reality not as detached information but as relationship—a relationship disclosed through the given world, through embodied experience, and through the subtle movements of the heart.

The convergence of science and Christianity within a transmodern, relational view of reality reopens a possibility largely closed by modernity: that the world may be enchanted not by rejecting science but by harmonizing with it. Enchantment here means perceiving the world as meaningful, addressable, and rich with depth; it means recognizing that knowledge is an act of relationship, that being is a gift, and that truth is encounter as much as explanation. In this shared horizon, Christianity and the sciences begin to see one another not as rivals but as partners glimpsing the same relational existence from different angles. Neither a Christian nor a scientific account replaces the other, yet both orientations to reality point toward a vision in which the world is intelligible because it participates in a deeper relational order. Indeed, we may be living at the threshold of a renewed way of seeing, a moment in which the sharp divides of recent centuries begin to soften, and a more integrated imagination becomes possible. If so, the Christian tradition, especially in its contemplative and sacramental dimensions, may have something essential to offer, not as a competing worldview but as a way of inhabiting the relational depth that the sciences themselves are revealing. This, then, is the quiet return of enchantment. It is not nostalgia but recognition. We were never living in a meaningless universe—we had only forgotten how to see its depth. To perceive it anew—through a science and a faith oriented toward the same relational horizon—is the invitation of the dawning transmodern age.