The Great Chain of Being, Part II

“Millions of miles from the remotest star

Which gleams upon the verge of mortal sight,

Far in the frozen wilderness of space,

The winged chariot of the spirit moved…

And all the spheres of earth and heaven reveal’d

Their mingled images in light divine—

No thrones, no hierarchies, but Nature’s laws

Alone, sublime, eternal, infinite.” (Queen Mab, Canto II)

The medieval cosmos was not small, but it was safe. It had an intelligible structure: a perfect sphere walled in by the angelic host, with earth at its center. The modern universe, by contrast, is stark, vast, cold, and void. If the heavenly spheres of the medieval world were propelled by their Creator’s love, the planets of the modern universe are moved by the impersonal laws of nature.

The chain of being had, in short, provided medieval man with a sense of place and purpose in a broader cosmic scheme. With the loss of this cosmic model, modern man likewise loses his footing, crying out, as Pascal did in his Pensees, that “the enteral silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread.” We, the lonely wanderers of planet earth, are left to ask ourselves: where to next?

One path by which we might regain our sense of place in the universe lies in the way of modern evolutionary theory. The theory of evolution not only explains phenomena that the great chain of being couldn’t account for, but also has provided us with a new model by which we might orient ourselves in the world, one less hierarchical, more relational, and more open-ended—not the chain of being, but the tree of life.

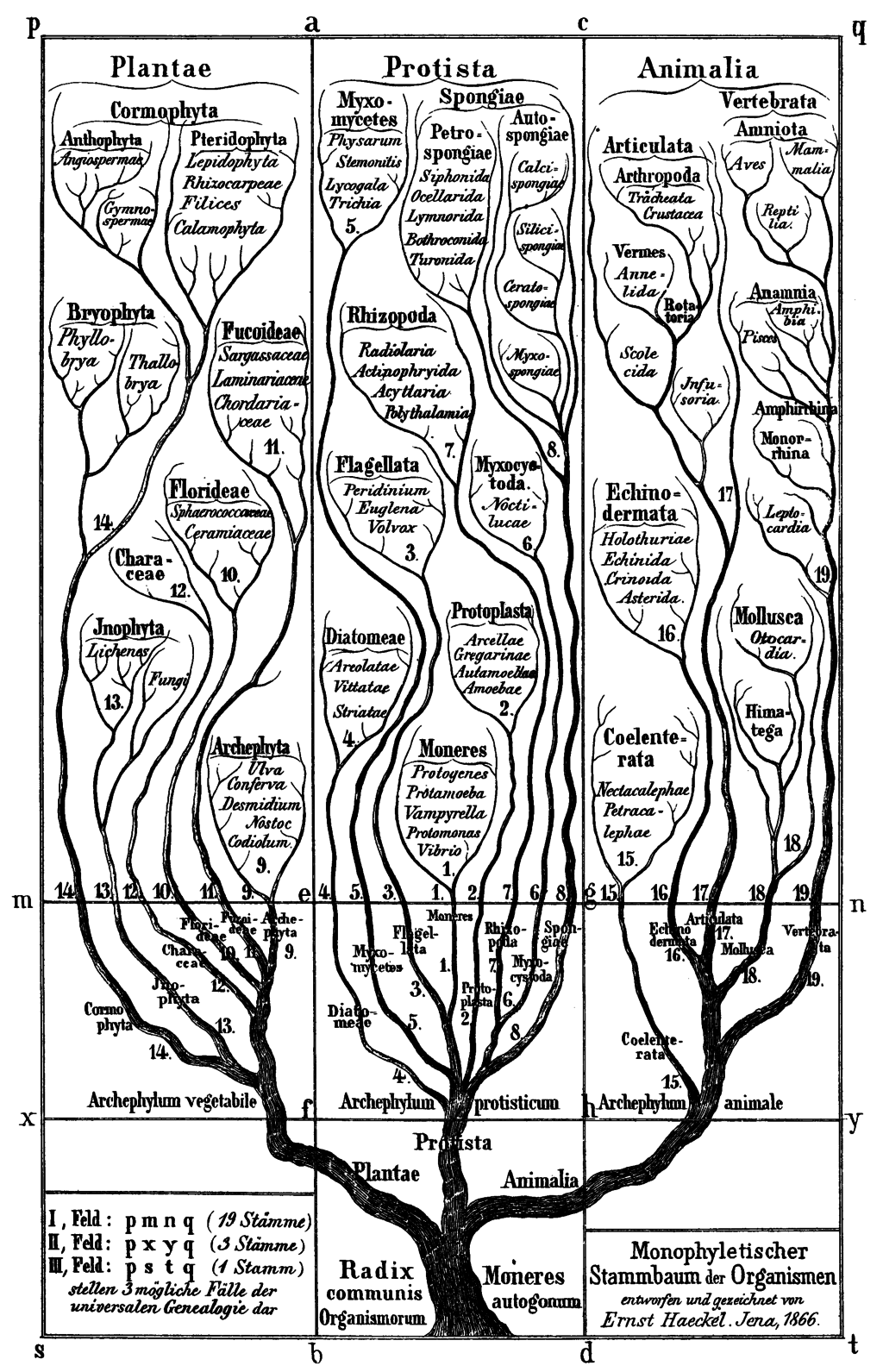

Ernst Haeckel, Tree of Life, from his General Morphology of Organisms, 1866

The chain of being faced challenges not only in astronomy, as I discussed in the last piece, but also in biology. The chain, we’ll remember, was originally imagined as a hierarchy beginning with God and descending to angels, humans, animals, plants, and finally minerals. This led naturalists to search for missing “links” in the chain, with some proposing mermaids as the missing links between sea creatures and humans. Apart from the lack of evidence demonstrating that mermaids exist, this stance became increasingly untenable with studies of the fossil record. The fossil record suggested that new classes of animals emerged in sudden, dramatic bursts rather than through a slow, steady progression. These sharp jumps pointed to major gaps in the natural order—a problem for the traditional model of the chain in which all lifeforms were supposed to exist continuously and eternally. More fundamentally, the rigidity of the great chain clashes with our own observations that change is in a constant state of flux, as things grow, change, and transform.

Acknowledging that change was a real force, some naturalists tried to rescue the chain of being by “temporalizing” it. The chain was no longer a static, immutable hierarchy but an active process, unfolding dynamically in real time. Thus, the chain of being became the ladder of becoming. Each rung represented a slightly more complex form of life than the one below it, with humans, the most complex of all, at the top. The entire history of life, then, could be understood as a progression toward humanity. Species were guided by this hierarchy according to a divine plan (in its Christian conception) or the laws of nature (in its agnostic reinterpretation). Gaps in the material order could now be explained as part of the process of becoming, as one species transformed into the next. Change was not only necessary but also inevitable. The ladder of becoming reinforced our sense that humans were more advanced than other species, offering a sense of importance without invoking a cosmic plan. And yet, it still failed to account for the full diversity of nature. Bacteria both outlive and outnumber humans, but at no point in their evolutionary lifespan have they attempted to become more human-like. And some relics of evolution, such as goosebumps, serve no obvious function in humans. A different framework was needed that could encompass the multiplicity and dynamism of the natural world.

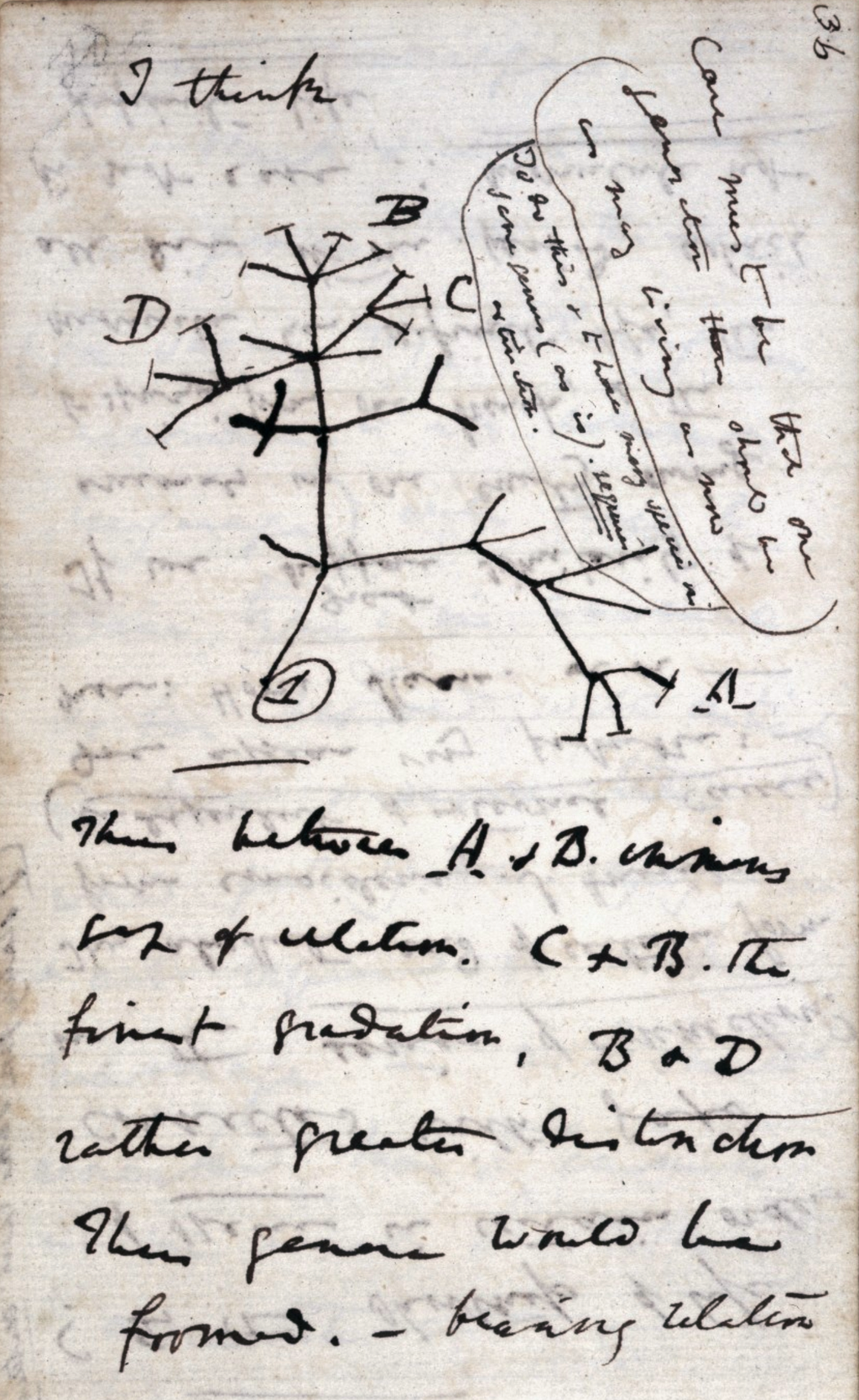

Darwin provided this new way of understanding life with his theory of evolution by natural selection. Today, we understand adaptive evolution as the process by which genetic variation allows a species to change in response to its environment. Adaptive evolution has given us a new model of how nature is organized, one to replace the great chain of being: the tree of life. The tree of life contains many diverging branches with no main trunk. Branches sharing the same stem represent species with a common ancestor. With no central trunk, the tree makes clear that there is not a linear, unbroken sequence of life that links minerals to fish to humans. Instead, the tree shows which species share a common lineage, and it seeks to explain how these species diverged. While the chain of being was goal oriented, the tree of life is process oriented. There is no single, highest form of life that everything converges toward. Species with increasing levels of complexity are possible, but they are a contingent result governed by local conditions. That complex lifeforms have emerged by chance may feel unsettling, since it pushes against our human instinct to find order in nature. But contingency is not randomness—change is constrained by the species’ evolutionary past and by its interactions within its current surroundings. Evolution is directed, but its progress is not predetermined.

Image from a 1505 edition of Arbre de ciència by Ramon Llull

Applied to our own lives, the tree of life helps steady our solitary sense of self. Our place in the universe springs from our relations within it, not from a rank on a metaphorical chain. Relationships, not hierarchy, become the lens through which we understand our identity. Genealogy—the web of relationships and history we come from—regains importance, not because the vocation of our ancestors locks us into a fixed place within a social hierarchy, but because their lives shape how we see ourselves and the world we inhabit.

In response to the question “who am I?”, our medieval thinker might point to his rank on a cosmic chain and our eighteenth-century naturalist to humanity’s position on the top of nature’s ladder. In place of these rigid identities, however, we can tell stories about ourselves, drawing upon our ancestral past and present experiences. Narrative replaces teleological thinking as the primary source of knowledge. There is not a pre-ordained “reason” or “purpose” for our existence; our values emerge from the choices we make and the history we have inherited.

Contingency enables human agency. The fact that things could have been otherwise means things can be otherwise. We are not resigned to some pre-ordained rung on a ladder or link in a chain; instead, we are active participants in shaping who we are and what our culture becomes. This is not isolated individualism. Just as genes constrain the course of an organism’s evolution without dictating it, our own familial and societal histories shape our choices without fully defining who we are. Understanding the genealogy of our own values helps guide our response to them, and the local community becomes the ecosystem in which our own interactions help shape the future we share. Human action regains its dignity as each choice becomes a means of communal participation in a living and breathing world.

Charles Darwin's famous “I think” sketch, from his Notebooks on Transmutation of Species, 1837. The first example of a phylogenetic tree.

Unlike a metal chain or wooden ladder, a tree is living, not dead. In the same way, our understanding of life is constantly changing in light of new discoveries and experiences. Viewed in this light, the chain of being represents one stage in humanity’s attempt to make sense of life, one “branch” in the larger tree. The deep historical roots of the chain are a testament to its appeal, even if it no longer reflects the world as we now know it.

The tree of life, on the other hand, aligns more closely with our lived experience. It recognizes life’s diversity while still maintaining a sense of order. A tree is not a vertical line, but it is not a directionless knot either. There is still a semblance of order in the progression of life, but its order is horizontal, not vertical. In other words, progress, whether in species, ideas, or inventions, is possible but not inevitable. Each new development builds upon what came before, but is also affected by chance, circumstance, and climate. Such a world may lack a predetermined structure, but it still invites awe: a quiet order arising from the innumerable, branching possibilities of life. And so, without invoking a transcendental framework, we can still affirm with Darwin that there is a “grandeur” in life, for, as he wrote in On the Origin of Species, “whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”