The Great Chain of Being, Part I

Vast chain of being, which from God began,

Natures ethereal, human, angel, man,

Beast, bird, fish, insect! what no eye can see,

No glass can reach! from infinite to thee,

From thee to nothing!—On superior pow'rs

Were we to press, inferior might on ours:

Or in the full creation leave a void,

Where, one step broken, the great scale's destroy'd:

From nature's chain whatever link you strike,

Tenth or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.

(An Essay on Man, I.237–246)

In his Essay on Man, Alexander Pope depicts a vision of the cosmos long rooted in Western thought: the great chain of being. In this cosmological scheme, the universe is suspended from a vast chain that emanates from God and extends to the simplest forms of life. A creature’s place within this fixed hierarchy depends on its balance of matter and spirit, with inanimate objects like rocks at the bottom, man (matter and spirit) in the middle, and angels (pure spirit) at the top. But lest we imagine that the difference between man and God is a mere upward stretch, Pope asserts that the distance to God is so vast that “No glass can reach!”, for God is not merely a being but is Being itself. If we, dissatisfied with our position in the chain, were to aspire to superior powers, the entire chain would break and chaos would ensue. Within this intricately connected chain, each being depends not only upon God but also upon one another, for each “link” must keep its place to sustain the whole. For much of Western history, the chain of being provided a coherent image of the universe, one that provided humanity with a clear sense of place and purpose.

Didacus Valades, Great Chain of Being, 1579

The idea of the chain of being first appeared in Plato. As A. O. Lovejoy argues in his seminal work, The Great Chain of Being, Plato constantly wrestled with the pull between the changing world we inhabit and the unchanging world of Forms. Plato’s Forms are abstract ideas, such as Justice or Beauty, which he saw as the true “essence” of material objects. The appeal of these timeless Forms is obvious: they offer a sense of stability in a world of constant flux. But if reality dwells in Platonic Forms, we might mistakenly conclude that we ought to turn away from the material world and contemplate these ethereal (if somewhat opaque) essences. Indeed, why linger in the world of change when the real resides elsewhere?

But Plato does not stop there. Instead, he orders us to stop our navel-gazing and march back down to planet earth, where these Forms take shape in everyday objects. And yet, how can the changing world be good if unchanging Forms are what is most real? Plato resolves this paradox by identifying “The Good” with the very act of giving goodness. According to Plato, a perfect, self-sufficient Good (i.e., God) would not be truly good if He did not share this goodness by creating everything possible. Perfect goodness naturally overflows, necessitating other beings to partake in it. Thus, the initial outline of the chain emerges: a perfect world emanating from a good God brimming with being.

Aristotle, Plato’s pupil, added two further strokes to fill-in this sketch. The first was scala naturae, or nature’s ladder. Aristotle posited that all beings exist on a continuum without clear boundaries between species. Continuity between species ensured that every type of being exists. This idea logically follows from Plato’s thought: for the world to be complete, one species must flow seamlessly into another. As I will discuss in my next essay, this belief in the continuity of nature would much later come under scrutiny when scientific discoveries revealed that nature was, in fact, full of gaps. But for Aristotle, nature admitted no gaps. Whatever was empty, nature would fill, thus mirroring the overabundant goodness of its God.

Closely tied to scala naturae was Aristotle’s idea of gradation. Aristotle thought all organisms are arranged hierarchically based upon the capacities of their souls. Plants, with a vegetative soul, stood at the bottom; humans, with rational soul, in the middle; and immaterial beings, possessing pure intellect, at the top. To Aristotle and his followers, this schema of creation as a rising, linear order helped to organize the immense variety of nature through a single, unified structure. Although neither Aristotle nor Plato fully developed the chain of being, they laid the framework for a cosmology—complete, continuous, and hierarchal—that would shape Western thought for centuries.

Raphael, School of Athens, 1511

The chain of being began in ancient philosophy, but it reached its fullest and most systematic expression in medieval Christendom. In the hands of medieval scholastics, the chain of being was personified: Plato’s abstract Good became the personal God of Christianity, his immaterial Forms, angels actively engaged in human affairs. Dante’s Divine Comedy offers the clearest picture of this transformation. Dante envisioned the cosmos as an act of divine love, flowing from a God who longs for His creatures to share in Him:

That which can die and that which dieth not

Are nothing but the splendor of that Idea

Which by His love our Lord brings into being.

(Paradiso 13.52–54)

In Dante’s model, being radiates from the empyrean (the realm of angels) through the heavenly spheres, and down to earth. As we descend the chain, the degree of imperfection increases. Earth, fixed at the center of the cosmos and farthest from God, was the lowest link on the chain. Thus, a geocentric cosmos was not intended to inflate man’s sense of worth, but to humble him.

Although the idea of a hierarchical universe may trouble our modern egalitarian sensibilities, medieval thinkers saw this ordering as both good and necessary. A cosmological hierarchy flowed naturally from a world seen as complete, fully expressing God’s goodness. As Aquinas writes in his Summa Theologica: “the perfection of the universe requires that there should be inequality in things, so that every grade of goodness may be realized” (I, q. 47, art. 2). Each being had a purpose, one it could fulfill only by occupying its proper place in the chain. Meaning was not something you constructed; it was embedded in the very fabric of reality. The medieval cosmos had a “built-in significance,” as C.S. Lewis writes in The Discarded Image, which was “a manifestation of the wisdom and goodness that created it.”

Applied to the political sphere, the chain of being meant that social hierarchy was an inherent feature of the world. Because the chain was divinely ordained and immutable, man ought to faithfully serve in the position assigned to him. Both the serf and the king were born with certain dispositions appropriate for their respective vocations. A serf’s duty was to be a serf and a king’s to be a king; to seek a different position would create social upheaval. This may seem like a convenient way for those in power to justify their position—and it often was. But it also provided man with a sense of place and purpose. Both the serf and the king reflected different aspects of God’s order, and only by maintaining these distinctions could society flourish. The cosmic and social orders reinforced each other: to question the order of society was to question God’s goodness.

Yet even medieval thinkers detected tensions in this cosmic vision. If the chain required God to create the world, how could creation also be an act of God’s free will? And how could a perfect God produce a world built on gradations of imperfection? These theological tensions were real, but they were not what finally broke the chain. Its true breaking point came with the rise of modern science, which presented a universe that looked nothing like the one medieval thinkers had imagined.

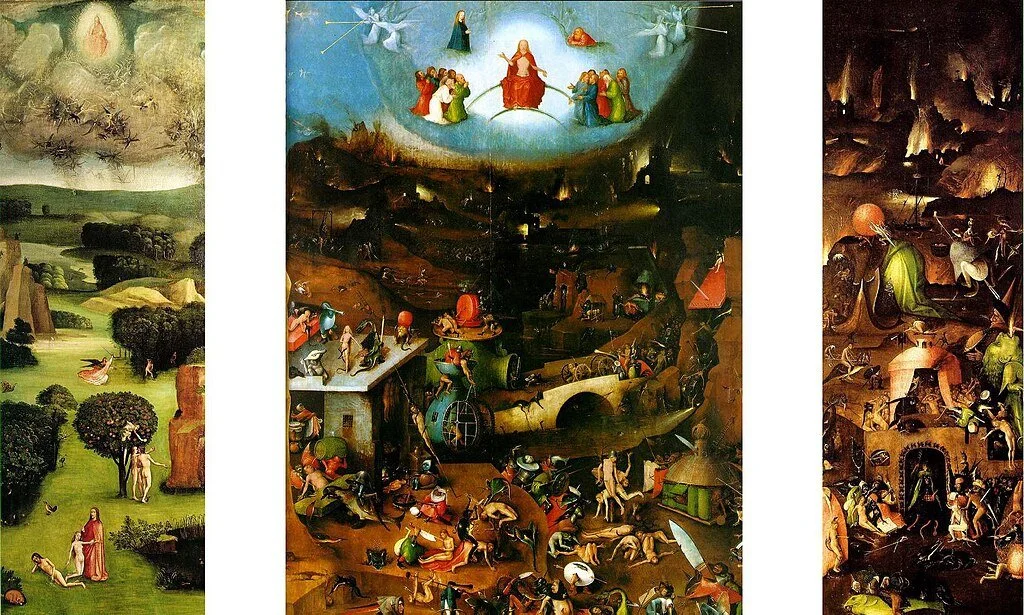

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgement Triptych, c. 1450

The first major challenge to the chain of being arose with Copernicus’s heliocentric model of the universe. Heliocentrism, by demoting earth to just one planet amongst many, raised the possibility that other solar systems could exist—a possibility later confirmed by Galileo’s telescopic observations. But if other solar systems could exist, then so could other sentient beings. This proposition ran directly counter to medieval cosmology. While man’s position on earth was by no means a seat of honor, it was still unique, for earth was where God chose to involve himself in human affairs. How, then, could the special status of man on earth be maintained if other sentient beings might also inhabit other planets many light years away?

This plurality of worlds opened into actual infinity with Newton’s studies on gravity. Because a finite, bounded universe would collapse upon itself due to gravitational forces, infinite space was necessary for cosmic stability. But if infinite space is possible, so too is an infinite number of worlds contained within. In the face of infinity, the cosmos lost its center, and the walls of the medieval world collapsed. If the medieval cosmos was filled maximally with being, the modern universe consisted primarily of empty space. Objects did not move because they needed to fill up space with being or because they were replete with love for their Creator, but because gravity acted upon them. This impersonal, infinite universe could no longer be held together by the enclosed, medieval hierarchy. As I will argue in the next essay, it required a new way of imagining order in a world without boundaries—a new model to reorient our understanding of the world and our place within it.