Worldpicture, Part II: The New Quantum Ontology

In her 1958 masterpiece, The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt characterizes the situation of the modern subject in the following way: “Modern man, when he lost the certainty of a world to come, was thrown back upon himself and not upon this world; far from believing that the world might be potentially immortal, he was not even sure that it was real.”

At a glance, these statements—that man is “thrown back upon himself” and uncertain about whether the world is actually “real”—might seem like vague, hand-waving generalizations about twentieth-century ennui. But in actuality, Arendt was speaking with razor-sharp precision about a pivotal discovery that changed the face of the modern age. She was talking about quantum mechanics.

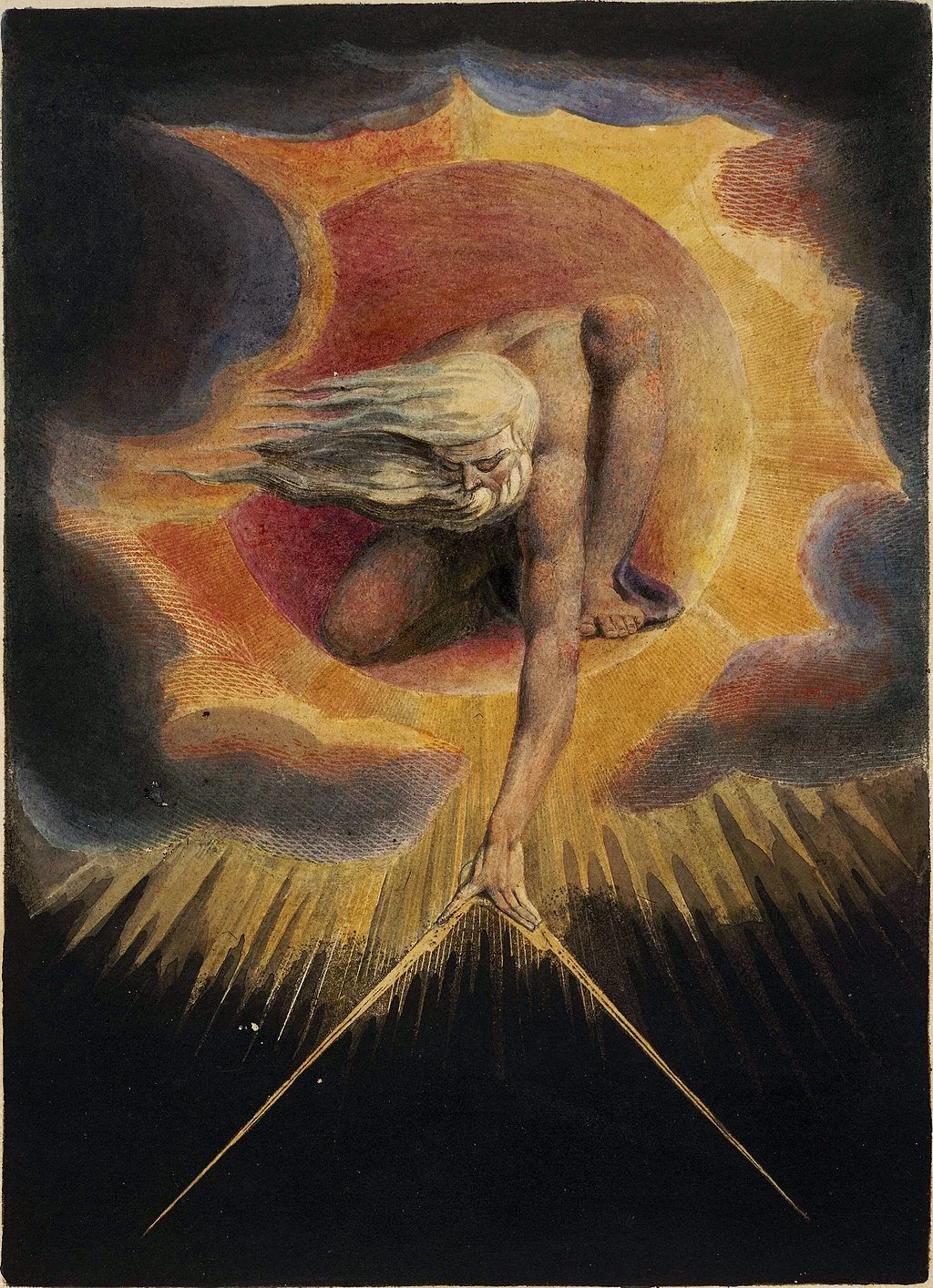

William Blake’s “The Ancient of Days,” a depiction of Urizen on the frontispiece to his 1974 book, “Europe a Prophecy.”

Quantum mechanics, with its particle waves, its entanglements, its cats half-dead and half-alive, is plainly very strange. But the truly strange thing about quantum mechanics is not the content of the theory: it’s the way that quantum mechanics threatens to upend our fundamental relationship to reality itself.

The theory, according to Harvard physicist Percy Bridgman, was “fraught with the possibility of greater change in mental outlook than was ever packed into an equal number of words.” If quantum mechanics holds up, wrote Bridgman in 1929, it will entail “the biggest revolution in mental outlook since at least the time of Newton, much bigger than Einstein, for example.”

Bridgman is claiming that quantum mechanics occasions a paradigm shift on the order of Galileo—a shift much greater than the disruptions from Einstein’s relativity or Darwin’s evolution. But what was the nature of this shift? Why did it have such radical consequences for the human epistemic enterprise? And why did it, according to Arendt, threaten the very “reality” of the world?

The truly radical thing about quantum mechanics is what it does to the possibility of scientific objectivity, or the existence of capital-T truth. Two of the basic tenets of quantum theory, as formulated by the Copenhagen physicists in the 1930s, initiate an entirely new relationship between human subjectivity and physical reality.

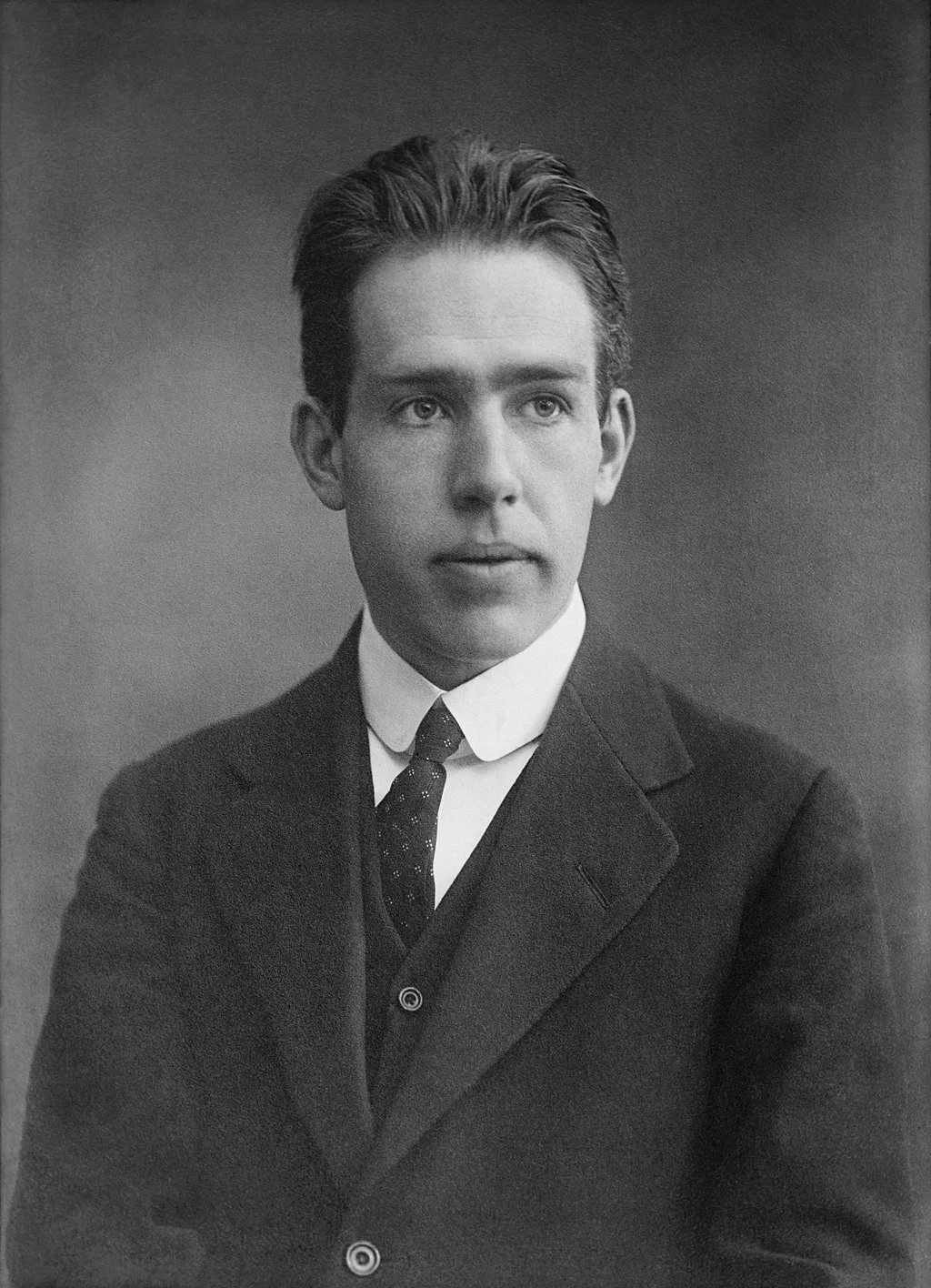

The first tenet is the so-called “collapse postulate.” The collapse postulate states that electrons exist as a wave until they are observed, at which point they “collapse” into a particle state. The implication, then, is that it is the human act of “observation” that changes the state of the electron in some mysterious and unspecified way. The second tenet is what Niels Bohr called the “principle of complementarity,” which holds that it is impossible to know different aspects of a particle (such as its spin along complementary axes) at the same time. The principle of complementarity was interpreted by Bohr and his contemporaries to imply that these different aspects of the electron do not exist before they are measured. That is, it is the human choice of measurement that determines the state of physical reality.

These two tenets, according to the Copenhagen physicists, reveal not merely an epistemic but an ontological feature of the cosmos. To illustrate this new picture, Bridgman suggested that we imagine that an astronomer has two telescopes: a planet telescope for looking at planets and a comet telescope for looking at comets. When the astronomer uses the planet telescope, he sees planets; when he uses the comet telescope, he sees comets. But this is not because the planet telescope “filters” reality to look like planets and vice versa; it would be as if the night sky were actually changing depending on which tool the astronomer chose to use. This is what the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics is claiming is happening in physical reality at the most microscopic level.

What does this mean? It means that reality is fundamentally subject-dependent. That is, it is impossible to know the world as it is in itself; I am only capable of knowing that which I have interacted with. To be clear, this is a stronger claim than the Kantian position that the mind “filters” reality in such a way that I can never get down to the pure, noumenal stuff. Kant’s claim is epistemic, whereas Copenhagen’s is ontological. Under the new quantum paradigm, the mind does not just filter noumenal reality, it plays an active role in constructing it. The “interspace” that composes phenomenal reality is locally dependent upon my consciousness; the “I” is impossibly tangled up in the world.

Niehl Bohr, circa 1910.

The goal of science shifts, then, from mapping the world in itself, to mapping patterns of human interaction with the world. Objectivity is replaced by objectifiability, which is a much more limited epistemic domain. Under this new paradigm, the only things we are capable of knowing are things that our minds have played a part in constructing. As Arendt puts it, “men at the beginning of the modern age still believed with Plato in the mathematical structure of the universe.” But now, with the advent of the new quantum ontology, “they believed with Descartes that certain knowledge is possible only where the mind plays with its own forms and formulas.” Science is no longer concerned with the natural world itself. “It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is,” said Bohr. “Physics concerns what we can say about nature.”

This amounts to what we might call an epistemic retreat, a striking revision of the fundamental task of science. Whereas previously, science hoped to secure an objective map of the physical world, it must now operate within a more limited epistemic domain. We are no longer fundamentally concerned with the world in itself, but rather the interspace between our minds and some mysterious world substrate that we cannot access and had better not think too much about.

This new ontology strangely reverses the Copernican shift that displaced man from the center of the cosmos. In the words of William Barrett, the modern subject “has now to confront himself at the center of all his horizons.” Or, as William Lovitt writes, “Man, once concerned to discover and decisively to behold the truly real, now finds himself certain of himself; and he takes himself, in that self-certainty, to be more and more the determining center of reality.” This is what Arendt means when she says that man is “thrown back upon himself,” that he is no longer even certain that the world is truly real.

Werner Heisenberg, 1933. CC 3.0

In the end, the price of the Copenhagen interpretation was the existence of an objective physical world: of a world that was, for all intents and purposes, real. To Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and the other leading Copenhagen physicists, quantum mechanics showed that the notion of a real world was yet another vestigial product of human naïveté destined to go by the way of phlogiston, epicycles, and luminiferous aether. As Heisenberg put it, “the idea of an objective real world whose smallest parts exist objectively in the same sense as stones or trees exist, independently of whether or not we observe them, is impossible.”

Such a radical epistemic revision within the scientific domain already constitutes, on its own, a major event in western epistemology. But what makes the whole picture even stranger is that this shift in the scientific paradigm prefigures, with astonishing accuracy, the shift in the general cultural paradigm in the later half of the century with the advent of postmodernism. Quantum mechanics, as formulated by the Copenhagen physicists, declared that objective truth was an impossible aim. The perspective of the observer, of the subject, was inextricably tangled in manifest reality. This is, in essence, what postmodern thinkers and artists said about human knowledge within a broader domain.

Postmodernism is, in the words of Steiner Kvale, characterized by a “loss of belief in an objective world.” It was catalyzed by the realization that there is no longer a “foundation to secure a universal and objective reality.” Capital-T truth is a fiction. What human beings encounter as truth is, instead, constructed through human action. As Richard Rorty puts it, truth is “made rather than found.” This is precisely the same shift from an objective reality to an objectifiable reality that we see within the quantum paradigm.

The destabilization of metastructure that I discussed in my previous essay bears a direct relationship to the overall decline of objectivity within the twentieth century. Indeed, insofar as it is possible to perform a linear regression on intellectual trends across an entire century, this would be the dominant movement of twentieth-century thought. We move away from given reality towards subjectivity; away from truth as given and objective toward truth as constructed and socially mediated; away from the security and stability of metastructure toward fragmentation and perspectivalism.

But how is it that quantum mechanics and postmodernism came to share these features? What is the causal connection between the two movements? And what alternatives remain for those who want to remain rooted in a world that is both objective and, for all intents and purposes, real? In my final essay, I will attempt to demonstrate that these two movements share an ontology because they share a genealogy: they are both forms of late-stage Cartesianism.