Worldpicture, Part I: Greek Tragedy, Postmodernism, and the Decline of Metastructure

What we talk about when we talk about the postmodern is not so much a specific moment in history as it is the sense of a deeper structural pattern running beneath a variety of cultural forms. It is, in short, what we might call a vibe. It is this vibe that allows us to recognize as part of a set the art of Andy Warhol or Damien Hirst, the philosophy of Foucault or Derrida, the atonal music of Schoenberg, or the literature of Knausgård or Murakami. I can sense, immediately, the unmistakable vibe of the fragmentary postmodern literary essay, and I can feel pretty confident that I’ll see it in A24’s next film.

The postmodern vibe is, in a low-resolution sense, kind of depressing. But this isn’t because postmodern art is about depressing stuff, per se. In fact, it’s often about stuff that’s totally quotidian and banal. The depressing thing about postmodern art is the fact that it makes the whole world seem meaningless. And often not even in a dramatic, Sisyphean, boulder-up-the-hill way. Just in a sort of low-grade what’s-the-point sort of way.

Compare this to a Greek tragedy. In a Greek tragedy, all sorts of horrible things happen. Eyes are gouged, women are abducted, infants are thrown off parapets. In a play like Trojan Women, the only positive moment in the 70-minute runtime is a girl talking briefly about a good-looking shepherd. Other than that, it’s murder and misery all the way down. And yet I leave Trojan Women feeling a sense of catharsis, of a cosmo-psychic release valve being tripped. This is exactly the opposite of the feeling I get from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where things are nice and boring and no infants are murdered and no one is dragged off by Achilles—but I leave the theater feeling suffocated, disoriented, and overwhelmed by the emptiness of the world.

What explains this disjunct? Surely the plays where bad things happen to people should make me feel bad and the plays where boring things happen to people should just make me feel bored. Why do the bad things make me feel weirdly at home in the cosmos and connected to a higher source of meaning, while the boring things lead me to the edge of the Nietzschean abyss?

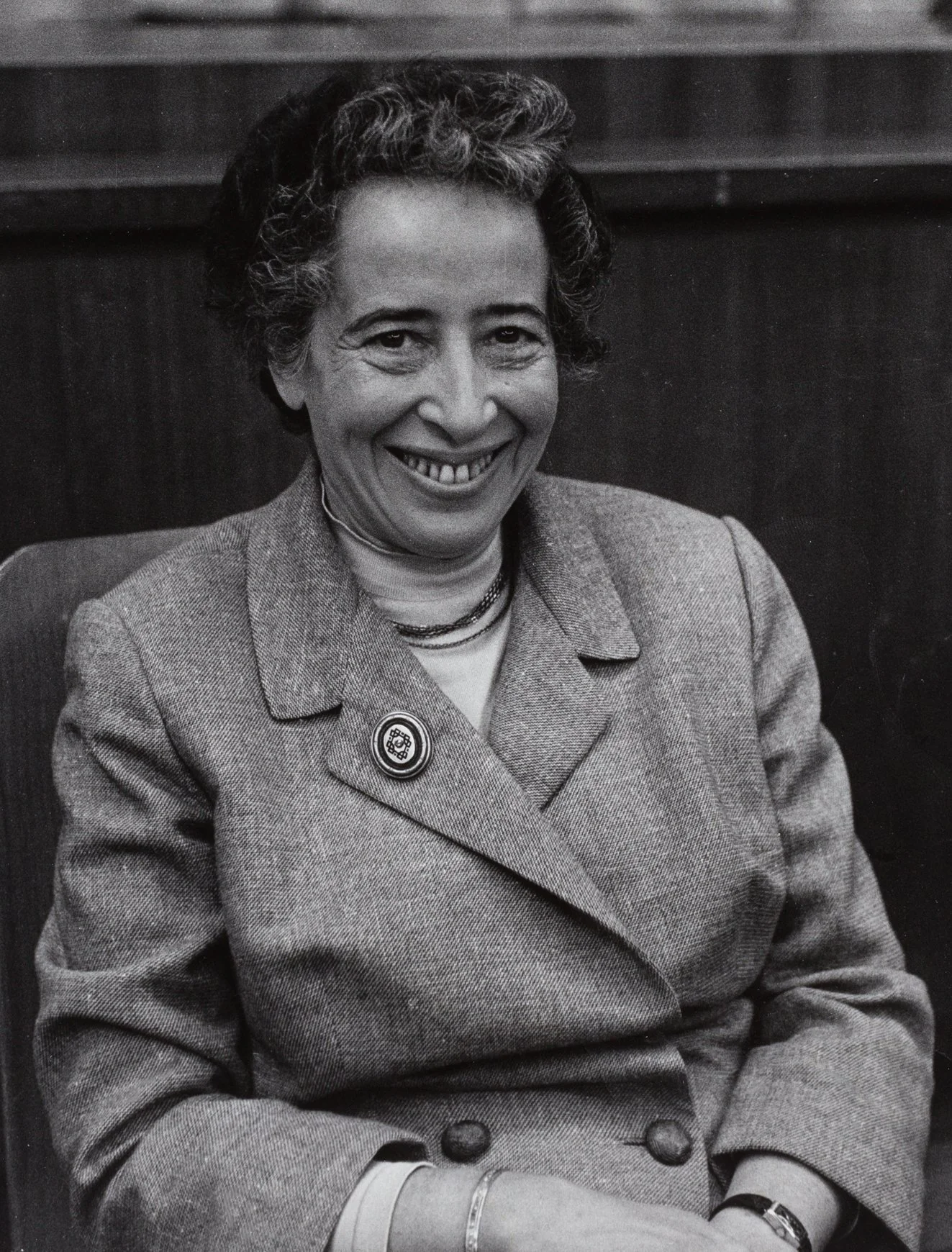

Hannah Arendt, 1958. CC 4.0

The answer, I think, has to do with what Hannah Arendt would call the postmodern experience of “World alienation” or “World loss.” Normally, when I am firmly situated in what Arendt would call “World,” I exist in the immediacy of objects and ends. To have a robust and vibrant World is to be embedded in a higher-order structure of meaning and purpose, where my sense of identity is granted to me via my position in this structure. When I am embedded in this sort of World, I know who I am, where I belong, and what my obligations are to other people. To be firmly situated in this World is to exist in a state of teleological stability; it is to have meaning and purpose.

World, in Arendt’s sense, is supported by what I want to call metastructures. Metastructures are higher-order conceptual structures: particularly the domains of the ethical, theological, and historical. Metastructures are higher-order conceptual structures—what I call elsewhere worldpictures or worldmaps—particularly across the domains of the ethical, the theological, and the historical They are maps of meaning that have the character of universals; they are fixed and objective, which means they apply to individuals regardless of their social identity, psychology, or lived experiences. Metastructures orient the individual teleologically vis-à-vis the rest of the lifeworld, helping us to make sense of chaos and providing structure and stability.

The primary movement of postmodernism was the dismantling of metastructure. Hence the term “deconstruction.” Postmodern thinkers and artists were engaged in a roughly two-step project. First, they revealed the ways in which metastructures were actually constructs—that is, products of human action—often taken to support structures of power, oppression, and control. Second, through exposing these metastructures as constructs, they undermined their claims to reflect a fundamental and universal reality. Instead of being seen as maps of psycho-cosmic meaning, metastructures came to be seen as the props undergirding dysfunctional and oppressive social dynamics.

The project of dismantling metastructure was often accompanied by the language of freedom and liberation. And indeed, within this new ontology, the atomic individual with its attendant independence becomes even more significant. Without an external structure to define the self and ground my identity, individual experience becomes paramount. We see with postmodernism an obsession with “standpoint:” the cultural, psychological, or linguistic conditions that give rise to things formerly believed to be objective. This explains the fragmentation that is so distinctive to the vibe of postmodern objects. Reality, under the postmodern paradigm, is revealed to have the character of one of Picasso’s cubist paintings: a face is a patchwork of perspectives from different angles, which may or may not add up to a unified whole. This is what T. S. Eliot captured in The Waste Land: the sense of the modern world as splinters of a formerly coherent culture. Knowledge, once thought of as a map, is now a kaleidoscope of local perspectives.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, c. 1495–1505

This is the central tenet of postmodernism: you cannot do away with perspective. It is what we might call a hyper-localized philosophy, where the view from somewhere has won an ultimate victory over the view from nowhere.

But there are serious downstream costs of abandoning the structures that, for centuries, have held the higher-order structure of the lifeworld in place. Formerly embedded in metastructures that granted teleological stability to the project of a human life, the modern subject is now unbound—facing a world where stable horizons have disappeared at the same as everything seems possible.

The modern subject can do, or be, anything he or she wishes. This is a position of maximum freedom, but also, paradoxically, of maximum obligation. And it initiates a new human dynamic. According to Byung-Chul Han, we have seen in the past century a shift from Foucault’s disciplinary society (in which the behavior of individuals is regulated externally through surveillance and punishment) to something that Han calls the achievement society. This is no longer, Han says, a society of “hospitals, madhouses, prisons, barracks, and factories” but of “fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories.” Within the achievement society, I become prisoner to my own project of self-actualization. The master–slave relationship is internalized: I am subject to a relentless process of mimetic self-reinvention. I may think that I am free, but this absolute freedom has become, under present conditions, the source of my compulsion. We have become entrepreneurs of ourselves.

Ennui and hyperactivity are then the twin faces of modern experience. Metastructure, in providing prescriptive boundaries on human activity, stabilized me teleologically in the world. It placed me in a structure of vocation, moral duty, and social obligation. This limited my freedom, to be sure, but also acted as a sort of bowling lane bumper on the oscillation of human experience. Facing a world where inherent meaning has fled, the modern subject must choose between languishing in the Nietzschean void or engaging in whatever brand of Huel-fueled hustle culture happens to be on offer.

As external structure fractures and disintegrates, I am thrust more and more back on myself: my auto-generated identity, my project of self-actualization, my subjective experience of reality. The “I” becomes more and more the center of the world. According to David Foster Wallace, the experience of reading the short stories of Kafka is like banging and banging on a door at the end of a hall, wanting nothing more than to get through, only to find that the door opens inwards, onto yourself. Such is the experience of the modern subject who no longer finds himself situated in a world where meaning is granted to him through external structures, but who now must discover, or create, this meaning for himself. This leads to the situation where no matter where he goes, everywhere and always, he encounters only himself.

But let’s return, for a moment, to the question of Greek tragedy. It is a bit clearer, now, why the plays of an Aeschylus or Sophocles, in all their pain and destruction, leave me in less despair than the plays of Beckett or Caryl Churchill. Greek tragedies take place in a world with a solid metastructure, one so solid, in fact, that the characters of tragedy possess little to no interiority. The opposite of the self-defining subject of the postmodern era is one whose existence is conditioned entirely by realities outside the self. The subject of a Greek tragedy is constituted and defined by a set of fixed relationships to gods, family, and fate. The central dramatic tension of these tragedies is that the individual is powerless before these binding relationships. The subject of a Greek tragedy is maximally embedded in a structure beyond himself.

The Theatre of Dionysus, the birthplace of Greek Tragedy. CC 2.0

Why is this existentially comforting, especially if it involves eye-gouging or being carried away by Spartans? I think there are two answers. The first is that we are comforted and reassured, by the vibrancy of metastructure, by the richness of World made manifest in Greek tragedies. Within this vibrant World structure, I may lose certain elements of freedom (conceived in the modern sense), but I am at the same time paradoxically returned to myself. This teleological situating tells me who I am.

The second answer is that Greek tragedies connect us to what Czesław Miłosz would call the second space, the sphere above human activity. Postmodern plays are enacted horizontally, entirely within the realm of the immanent. Greek tragedies, on the other hand, take place largely on the vertical axis. They connect us to the higher orders of deities and destiny. If there is, as I suspect, a profound sense of loss, or at the very least, an intuition of absence, when it comes to the realm of transcendent meaning, there is something profoundly cathartic about this kind of experience. It fulfills a need of the human soul.

The postmodern paradigm shift was primarily a cultural phenomenon: it took place within the domains of art, literature, and philosophy. But the fundamental movement of this paradigm shift—the movement away from objective reality and towards reality as subject dependent—also took place within an entirely different domain of human knowledge. In my next essay, I’ll look at the unexpected presence of the postmodern paradigm in the new scientific world picture arising from the development of quantum mechanics.