Worldpicture, Part III: The Cartesian Roots of Quantum Theory and Postmodernism

Quantum mechanics and postmodernism share two basic properties. Both movements undermine the possibility of objective maps of the world, of capital-T truth. And both establish the subjective as the ultimate criterion of the Real.

"Figure of the heavenly bodies", an illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic conception of the Universe by Bartolomeu Velhomade, 1568.

What emerges from both theories is a sense of the world as hyperlocalized, where truth, insofar as it can be known at all, can be known only through the perspective of the individual. General, higher-order truth, truth of the sort captured by the words metanarrative and metastructure, is not just subject to scrutiny. It is, in principle, impossible.

But what is the nature of the connection between these two theories? We might assume that one “caused” the other. But this is too strong an assertion. First of all, the ontology emerging from the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics was never clearly articulated, even within the physics community. Second of all, the intellectual movements that immediately preceded postmodernism were well underway by the time quantum theory was developed.

The more compelling connection between the two theories is, instead, that they share a genealogy. Both quantum mechanics and postmodernism are forms of late-stage Cartesianism; they represent the final stage, the denouement, of the epistemic revolution initiated by Descartes in the seventeenth century.

Descartes, with his cogito, shifted the fundamental relationship between mind and world. The world, as previously given in experience, was no longer to be trusted. The mind became epistemically primary: the only things that were truly real were the contents of mental perception. By establishing this point of absolute certainty within the mind, Descartes hoped to secure the foundations of all future knowledge. From the leverage of this single, indubitable point, he thought we might build outwards toward a unified world picture, secure and objective, once and for all. But in order to establish the mind as absolutely certain, Descartes subjected the world beyond to an absolutizing doubt. This doubt has become, according to Hannah Arendt, “the self-evident, inaudible motor which has moved all thought, the invisible axis around which all thinking has been centered.”

Portrait of René Descartes by Frans Hals, 1649.

The advent of this Cartesian doubt is what creates the modern subject. If the world is cast within the shadow of doubt, and truth is to be found within the mind, then the subjective becomes the ultimate criterion of the Real. This amounts to a Copernican transformation in the centrality of the subject. “Man,” writes William Lovitt, “once concerned to discover and decisively to behold the truly real, now finds himself certain of himself; and he takes himself, in that self-certainty, to be more and more the determining center of reality.”

For three centuries, the Enlightenment project was fueled by the tension between these two aspirations: the security of subjectivity, on the one hand, and the hope of objectivity, on the other. But the subject dependency introduced by quantum mechanics and by postmodernism has forced the Enlightenment project to a crisis. The essence of an objective world picture lies in the fact that it is a map from which perspective has been abstracted. It is a view from nowhere. In claiming that the world only comes into being through our interactions with it, both theories undermine the possibility of objectivity in principle. It is impossible to do away with standpoint; all knowledge is knowledge from somewhere. There exists a fundamental trade-off between a local Cartesian certainty and a global conceptual objectivity.

Faced with this trade-off, both the Copenhagen physicists and the thinkers of the postmodern school doubled down on the subjective at the expense of the objective. The world, formerly conceived as a structure that was fixed and objective, shatters into a kaleidoscope of localized perspectives. This explains the fragmentation that is so characteristic of postmodern art and literature. The world now has the character of one of Picasso’s cubist paintings: a patchwork of impressions from many angles, which cannot, in aggregate, add up to a unified whole.

Objective world maps—of the sort that used to be found in metastructures like fixed moral codes, traditions of religious praxis, and inherited history—liberate us from the confines of atomistic subjectivity. The self comes into being through relationship to others, the past, the cosmos; self-definition breeds anomie and loneliness. This is why we see, throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and increasingly throughout the twenty-first, trends in this direction. “World alienation, and not self-alienation, as Marx thought, has been the hallmark of the modern age,” writes Arendt. In the modern world, this “deprivation of ‘objective’ relationships to others and of a reality guaranteed through them has become the mass phenomenon of loneliness.”

These “philosophies of perspective” clearly have downstream costs for the vibrancy of the human lifeworld. But where do we go from here? The debates surrounding quantum mechanics may, in fact, provide a glimpse of a path through the matrix.

The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, which is the interpretation I have been referencing up to this point, remains the “standard” way of understanding what the mathematics of quantum theory is saying about the material world. But Copenhagen is not the only way to translate quantum theory; in fact, it has provoked serious criticism and dissent from the very beginning.

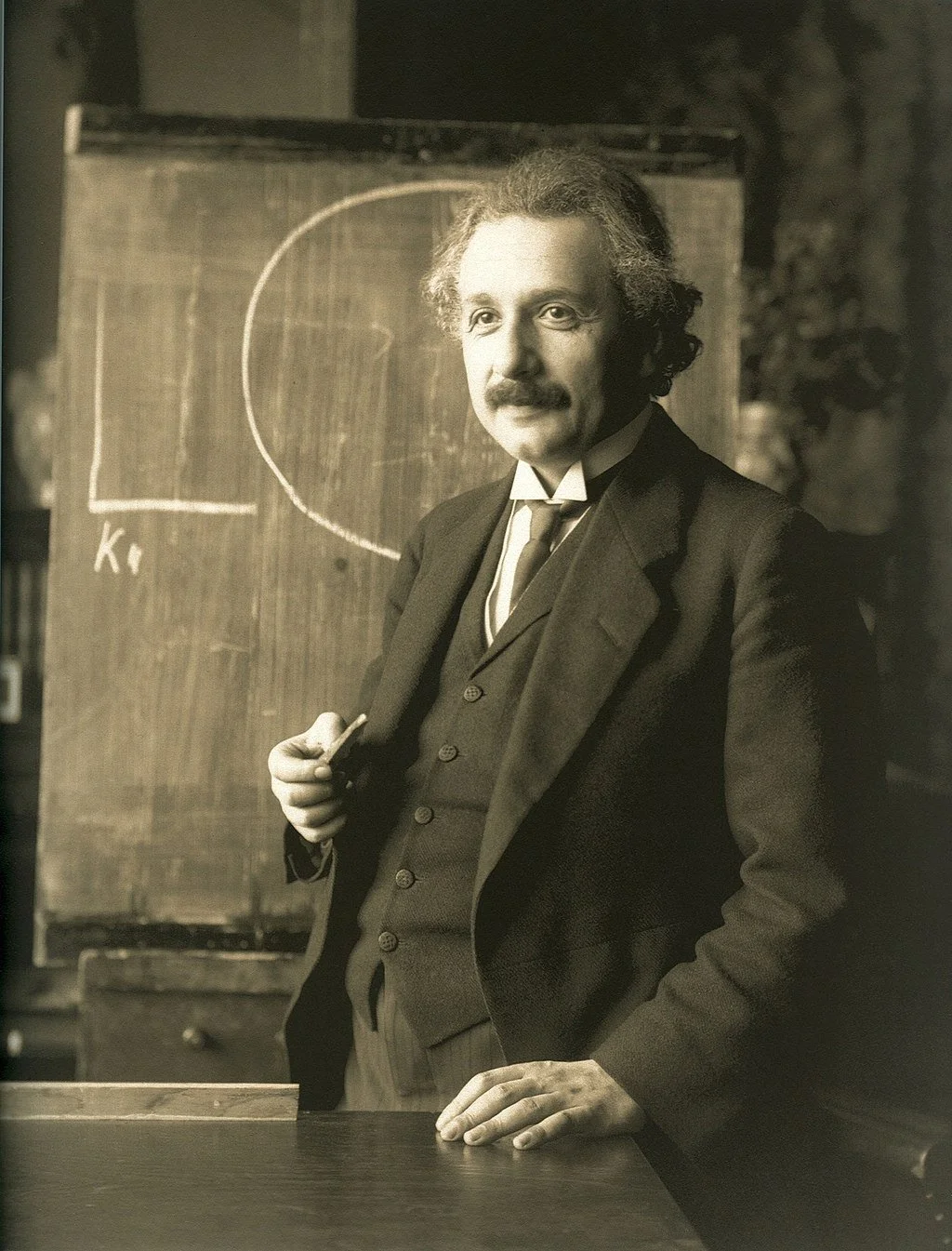

The most notable of these critics was Albert Einstein. The theory, he said, “reminds me a little of the system of delusions of an exceedingly intelligent paranoiac.” There are complex, technical reasons why Einstein resisted Copenhagen, a theory that some claim to have led to “a defeat of reason within modern physics and to an anarchist cult of incomprehensible chaos.” Insofar as it is possible to summarize Einstein’s objection, for him, abandoning the possibility of objectivity was tantamount to abandoning the very possibility of science itself.

Albert Einstein during a lecture in Vienna in 1921.

The existence of a real world, with properties that are fixed and independent of the human mind, is not something that science can prove using its own techniques. It is rather something that we must first posit or assume in order to be able to do anything like science in the first place. It is “the postulation of a ‘real world’ which so-to-speak liberates the ‘world’ from the thinking and experiencing subject,” wrote Einstein. “The extreme positivists think they can do without it; this seems to me to be an illusion, if they are not willing to renounce thought itself.”

Here, Einstein forces us to reevaluate our Cartesian priors. We must assume the existence of a fixed world structure in order to be able to do anything like science. But we cannot prove, with the sort of apodictic certainty of which Descartes dreamed, that these structures exist.

There exists, therefore, a sort of “gap” between the objects that we experience in the world and the frameworks we must adopt in order to make them cohere. Adopting these organizing frameworks is a necessary precondition for world coherence, yet it is a step we must take without the security of absolute certainty. We access these frameworks only through what Einstein calls an “intuitive leap,” which is based upon a “faith in the rational ordering of this world.” The necessity of this leap discloses what Einstein called the “irrational, or mystic element,” which “adheres to physical science as to every other branch of human knowledge.”

This points us, I think, away from a Cartesian epistemology, with its emphasis on absolute certainty, toward what I want to call a coherentist epistemology. This coherentist epistemology is one in which frameworks are adopted based on their ability to organize patterns in the world, to provide coherence to otherwise-disorganized phenomena. These two epistemologies differ fundamentally in their order of operations. Within the Cartesian frame, knowledge of the world is built from the ground up of interlocking blocks of absolutely certain propositions. The parts are combined, eventually, into a unified whole. Whereas within the coherentist frame, the world structure is first assumed to possess coherence from which point individual elements can be contextually investigated. The whole must come before the parts.

It is common to speak of our cultural moment as “disenchanted” or “desacralized,” but this framing is deceptively Nietzschean. God is not dead, the world is not empty of inherent meaning; it is rather that we have done away with the conceptual and cultural forms that allow us to receive and transmit those meanings. This has left us with a bifurcation between reason-impoverished religious forms (dogmatic evangelicalism, New-Age woo, Barnes & Noble pop astrology) and the “reasonable,” “scientific” framework that explains the world in a purportedly rational but meaning-deficient way—and that ultimately cannot support robust forms of human flourishing.

When it comes to the social and cultural issues that are downstream of more abstract epistemological and ontological concerns, Einstein’s logic still applies. Our culture is not built to support what Simone Weil calls needs of the human soul, which include a structured vocation, a grounding in place and past, embeddedness within a social and moral order, and access to the higher-order transcendent reality. These goods do not clearly demonstrate their value within the Cartesian reductive-materialist paradigm. It is therefore crucial that we recognize that the post-Cartesian reductive-materialist frameworks will never be sufficient to support a robust and expansive human flourishing. As long as the modern subject is bound by the criterion of certainty, he will not be able to make the “intuitive leap” to metastructure that is required for a robust teleological grounding in the world.

Re-accessing metastructure is easier than we might be tempted to believe. The cultural repository is there, waiting for the renaissance that will allow us to once again access the richness of our intellectual, theological, and political traditions. There is the danger, of course, of erring too far in the direction of reaction, of attempting to revive a past moment of cultural vitality by copy-and-pasting it into the present day. Those who are doing this are LARPing, and their vibes are bad. The project of cultural revitalization, instead, involves the task of translating metastructures—of adapting them to the never-before-seen conditions of our present historical moment. This is a task, not of atavistic reaction, but of radical innovation. And it must be guided, not by the stringent demands of the criterion of certainty, but by the principle of coherence.