Recovering Christian Visual Literacy, Part II

Some might question how significant or widespread this casual approach to biblical imagery is. Couldn’t we surmise that the design of our church’s slideshows simply reflects the unique perspective of a particular staff member or committee? If images are thematically appropriate, why insist they be anything other than illustrations that inspire us as we sing hymns? No doubt that’s what many in our parish would say. I had initially wondered if the persistent and expedient use of images during Mass was an anomaly until I noticed the same loose approach to sacred art in our church’s weekly bulletins and social media pages. It’s less conspicuous, but from that material I found a thread leading beyond the church’s walls. Comparing these other materials to the various forms of communication in parishes nationwide, one finds a consistent aesthetic. I was on to something, but I could only identify the issues at work once I had traced a migration from our church’s projection screen to its printed and online media. I then saw that mirrored in the look and feel of media in other churches. The undifferentiated use of images I was experiencing in the midst of liturgy had indeed pointed me to a broader trend.

So, how can we remedy our lack of substantive visual theology? I came across one solution recently. On the occasion of an essay I’d written centering on the Pantocrator image, a friend sent me the link to a livestreamed “Contemplative Eucharist” led by Fr. Laurence Freeman, director of the Bonnevaux Centre for Peace. It is the international home of the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM). Freeman had, coincidently enough, visited our church for a talk and meditation demonstration a few years ago. I’ve followed the teachings of this Benedictine monk and leading Christian contemplative for some time now. There’s a certain irony in the fact that, having once passed briefly through our church, Freeman now returns, in this essay, as someone who has used sacred art in a way that my church can learn from. The excitement I felt about his past visit returned in a new way when I watched the video and saw how he had integrated an icon into his teaching. Although for me Freeman’s unconventional services could never replace going to church, this recent liturgy demonstrated how a sacred image can nourish us in the context of worship.

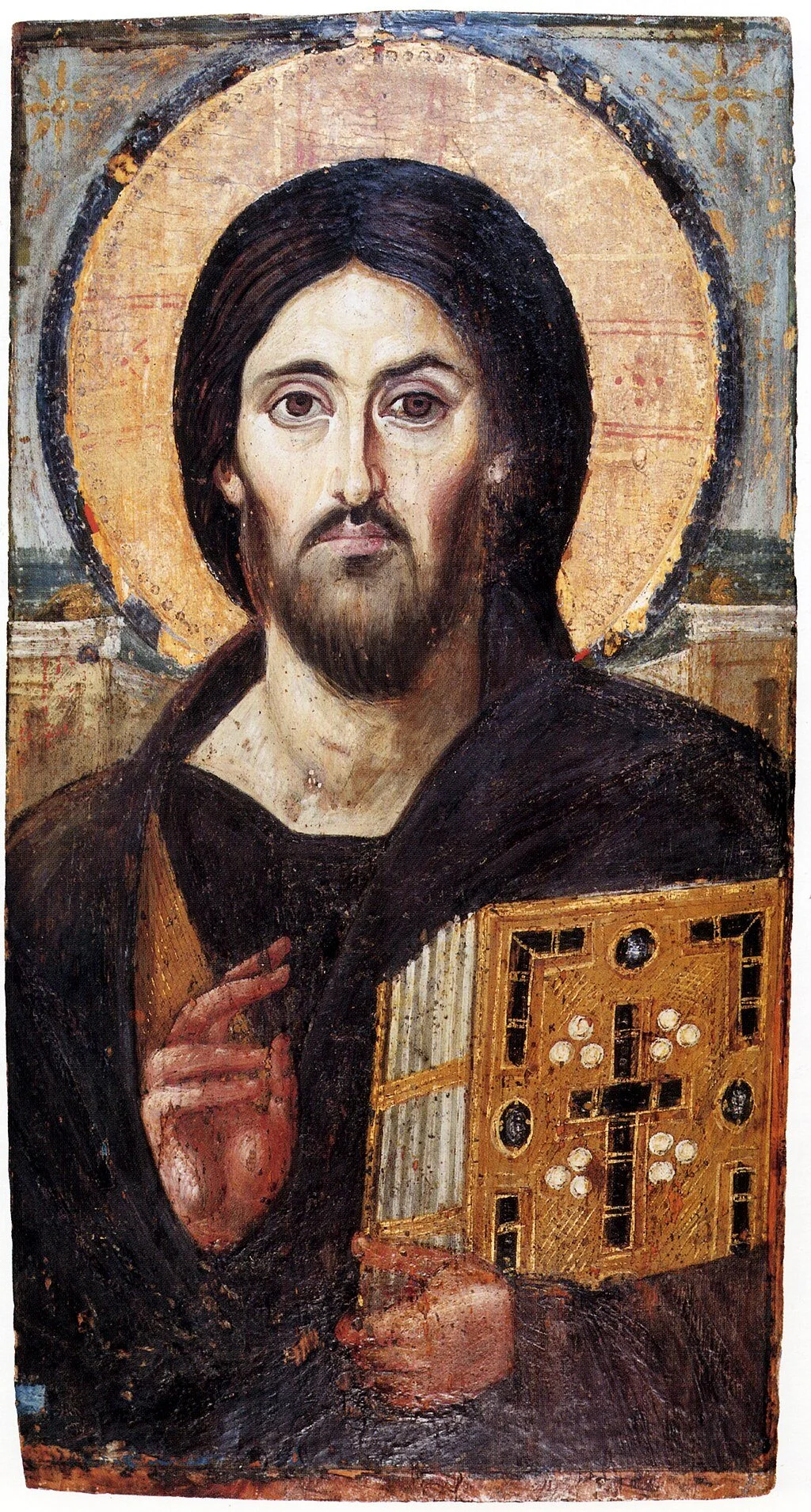

Christ Pantocrator, a 6th-century icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai

Freeman’s contemplative Mass is unadorned. Simplicity, silence, and stillness are its defining attributes. Inwardly focused, it’s built around contemplative prayer. Scripture is read and liturgical rubrics are followed, but Freeman also provides commentary throughout the Mass on the day’s theme. On this particular Sunday, the theme was “Christ the King,” and Freeman showed the congregation the famous Pantocrator icon from St. Catherine’s monastery in Sinai. For more than ten minutes, he highlighted its most notable features, guided the congregation in contemplative viewing, and linked the icon to the day’s theme by showing how it expressed Christ’s nature. I was amazed at the ease with which Freeman had fit study of and meditation upon an image into worship. He was, in essence, mediating a communal encounter with the icon as a site of revelation.

What we’re treated to each weekend is vastly different—a symptom of the extremes of digital culture. Our world has conditioned us to accept without question this uncritical combining and presenting of a taxonomy of images that includes more than a cross section of famous art connected by theme. The expansive reach of modern media adds to the mix of reproductions from illustrated Bibles, contemporary paintings of Jesus, Christian-themed stock photos, and picturesque landscapes. Many appear over and over in different churches, functioning interchangeably on different occasions. Although our parish absorbs this motley combination of images in compressed form, the same images are deployed more broadly across various Christian institutions. The result is a heterogeneous visual field shaped more by availability and convenience than by theological intention. And the mentality reflects a society of image overload that fails to encourage lingering or return. Sacred images become momentary impressions rather than opportunities for sustained attention. Lack of careful selection also weakens the sense that any one image matters enough to dwell with. Freeman’s example teaches that certain images, chosen with the right intention, can provide us new insights when aligned thoughtfully with Scripture. Ultimately, the power of sacred images is ignored when they’re chosen for emotional accessibility or familiarity rather than their potential to challenge how we live our faith. And when circulated freely and disconnected from catechesis, the intended meanings of these same images are lost to highly individualized and unstable interpretations.

Yet, there are many ways sacred images can be employed to ground us and cultivate our attention while also providing an antidote for the deleterious effects of a distracted society. A church can encourage repeated encounters with the same image over time to allow meaning to deepen. Providing space for quiet looking before interpretation can help restore the image’s capacity to “speak to” the viewer, while making its presence more deeply felt. Situating images within Scripture, liturgy, and tradition can help congregations experience them as part of a living theological whole. Demonstrating practices of attentive, prayerful seeing rather than leaving images to function autonomously would be part of teaching how to look—not what to think immediately—so perception itself becomes spiritually trained. Those with the knowledge can also guide a church in attending to how composition and the formal elements of art carry theology, beyond what an image simply depicts. Churches can work to recover shared ways of looking together to resist overly subjective approaches to interpretation. And by accepting the resistance or strangeness of some art, allow images to unsettle, challenge, or remain partially opaque rather than trying to force immediate clarity or comfort.

What would it mean for the Church to redeem, rather than merely adopt, digital media? Now, when I gaze at reproductions of sacred art during Mass, I can’t help but think about the immense potential their easy accessibility holds—and how readily I’d give up self-administered quizzes on style and iconography to draw on the wealth of images the internet provides in shared, formative encounters, where the Church learns to see Christ together through art.