Is There a Modern Potlatch?

Picture a grand destruction of wealth. What image pops into your mind? A Jokeresque fire? A stock crash or a nuclear bomb or a cyberattack? How do you feel about this? What if grand destructions of wealth were not world-shattering events, but rather world-making ones? In the early twentieth century, scholars of culture considered this interplay between destruction and creation in the form of the potlatch. In The Gift (1925), the anthropologist Marcel Mauss defined the potlatch as a ritualistic destruction of wealth by one group or tribe for the purpose of outdoing the elimination of wealth by the other group. Such evanescent and reciprocal displays of grandiosity, through the struggle between groups, served as a type of obligatory gift giving, creating social cohesion. I ask if this practice exists in modern societies and offer three possible responses. By doing so, I examine the relation between the “primitive” and the “modern” and thereby the substance of each.

First, let us briefly peek at how the words “primitive” and “modern” have been problematized—made more complex—in contemporary academic-inflected settings. Each term can refer to time, place, or both—and people trapped within or in between these slippery signifiers. Liberal pluralism would argue that no society is primitive, that labeling groups such as the Aboriginal Australians as primitive is the work of the powerful imposing their will on groups they see as different. Mauss, reflecting these linguistic and conceptual quandaries in 1925, believed the potlatch to be practiced by “societies that we lump together somewhat awkwardly as primitive,” such as the Tlingit and Haida in the Pacific Northwest as well as the Polynesians. For some, how primitive your society is can be determined by its level of “socio-cultural integration:” are you part of a band or a tribe? A chiefdom or a state? The lower the integration, the more primitive, according to this theory. “Modern,” in the temporal sense, can be deployed as a wall of separation between us (now) and them (back then); this wall is constructed through linguistic claims collectively called “modernity talk,” which can vary in their representations of reality. My exploration here considers Mauss’s conception of the potlatch instead of casting a net over a wider source base. I made this choice because his cross-cultural, universalizing approach blends well with mine.

Underwood & Underwood, “The fantastic Potlatch Dancers, Indian Village of Klinkwan, Alaska.” (1904)

To more firmly cement our understanding of the potlatch, we must consider its essential connection to play. Mauss observed agonistic, or competition-related, elements in the potlatch. The ritual became a vehicle to express what he called “rivalry and hostility” at levels from the intratribal to the international. This concept of struggle was crucial to historian Johan Huizinga’s reflections on the “useless,” leisurely, ritual character of play in its broad meaning, that which is not work. In the anthropological Homo Ludens (published in Dutch in 1938 and expanded in English translation in 1949), Huizinga builds upon Mauss’s emphasis on honor and obligatory reciprocity by highlighting the weight of the ritual where “the slightest blunder invalidates the whole action. Coughing and laughing are threatened with severe penalties.” The potlatch is play but is also serious. In a practical sense, the ritualistic destruction of wealth is useless though done in a solemn manner. Does this agonistic ritual—identified as “primitive” by Mauss—just belong to the past or does the potlatch appear in the so-called modern world? We will now look at three ways of answering that question.

What if the modernity talk around the potlatch was justified? Such a position grants that sure, some version of it happened in most premodern societies—even in Greece, Rome, and pre-Islamic Arabia—but it occurs no longer in these enlightened times. In other words, the concept of the modern potlatch is an oxymoron. Here is some possible evidence. If the potlatch is only found in non-modern cultures, one reason would be that the scale of human organization is much larger today than in the societies under direct anthropological study such as the Haida. The whole tribe physically congregating at a certain location to watch material destruction is not possible in the contemporary era. Second, the potlatch is tied to the logic of gift, which exists in lesser form in a society based on capitalist or socialist forms of exchange. The obligations to not only give, but to receive and reciprocate created thick ties that are largely absent in today’s culture of networking and social media friendships. Third, Huizinga claims the potlatch “hinges on winning, on being superior, on glory, prestige and, last but not least, revenge,” which is sublimated under more innocuous competition such as organized sport with an overall ethic of liberal pluralism, the kind that thinks “primitive” is a bad word. All-out destruction is moderated and mitigated by risk management and entertainment. Ritualized violence upon objects is a thing of the past, or so the argument goes.

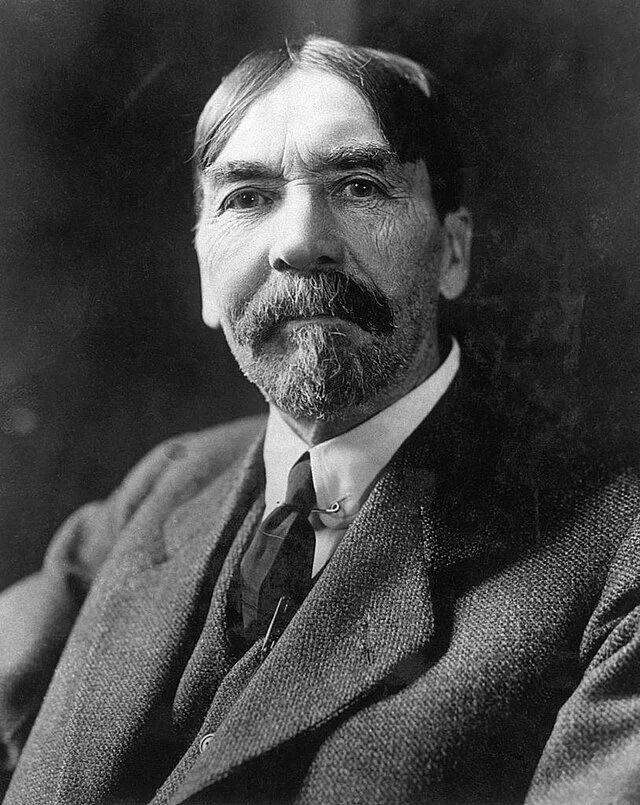

Photograph of Thorstein Veblen

A second response to the question of the modern potlatch sees it as a form of what Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption.” In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen states that the higher social strata consume luxury goods not because they have to in order to survive, but for “reputability,” to display to others. This argument can still accommodate some modernity talk; obliteration of material goods functions differently than sumptuous showcasing. However, both the potlatch and the luxury spectacle are forms of consumption through their status as a means for social experience. See many of the videos of the celebrity YouTuber Mr. Beast, in which money and luxury objects like yachts feature in the consumptive spectacle of destruction. Yes, the ties might not be as thick, but they are still present under the ethos of industrial capitalism. Just as in “primitive” times, the group leaders, who have most of the wealth, perform destruction for their rivals and their social inferiors. Who can match Mr. Beast and Amazon’s $100 million show? Though modern life is bigger than the scale analyzed by Mauss and Huizinga, the number of ties allows conspicuous consumption to be disseminated to anyone with an internet connection. The middle classes in the global market may attempt to engage in conspicuous consumption, but this is a consequence of scale and general increases in wealth. If nothing else, there are more potlatches today, says this line of reasoning, not fewer.

Consuming from necessity and consuming for social status do not comprise all types of material expenditure. For this third account, Veblen may not have anticipated what I call “inconspicuous consumption,” which can be defined as the scale of disposable waste in quotidian settings produced by modern humans. The amount of plastic, oil, and greenhouse gases used for daily functions, such as eating and mobility, is not necessarily meant to show off. Often done alone or in smaller groups, inconspicuous consumption does not serve the end of social cohesion. The logic of the gift may not be present, but this wealth, upon use, is destroyed. The potlatch of the ordinary, like the potlatch of “primitive” societies, contains both world-shattering and world-making powers. The environment is destroyed and remade in the image of inconspicuous consumption. The agonistic element, like consumption itself, becomes internalized. Inconspicuous consumption means that the game is within oneself.

Despite the differences, there are similar elements present in these three responses to the question of the modern potlatch. All involve some degree of modernity talk. As much as there may be some equivalent to the potlatch among the global elites of the twenty-first century, property owners are not often burning their own profitable buildings. And though there is certainly considerable waste nowadays, the anthropological concept of the potlatch was defined using the framework of the primitive by those who considered themselves modern. Yet there is an element missing from all of this: in Mauss’s conception of the gift, obligation extends beyond giving and receiving, and even beyond reciprocation. Part of the gift is the obligation to sacrifice. Mauss mainly considers contract sacrifice, where the gods are bound to reciprocate an offering by a human. But what if sacrifice, and the logic underlying the potlatch, could be more than that? Sacrifice takes its fullest form when free and gratuitous. Something is destroyed in free sacrifice, what Iris Murdoch calls the “anxious avaricious tentacles of the self.” Through the destruction of this part of the self, a new world for others emerges. And this new world gives life and peace.