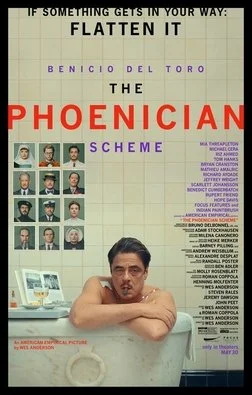

Human Rights and Humanity in “The Phoenician Scheme”

In Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme (2025), Anatole Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro) has “a habit of surviving.” A highly successful, idiosyncratic businessman who squeezes as much profit as he can out of his deals, Korda constantly faces attempts on his life in relation to his mysterious business endeavors. He has nine sons and one daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), who is about to take vows as a nun. The film’s plot follows along as Korda summons Liesl to get involved in the “Phoenician scheme,” a building project he is setting in motion to alter the social and economic landscape of Phoenicia to his benefit.

As with everything Wes Anderson, there are elements of the absurd and the fantastical in this film. Korda has nine sons because he adopts children in addition to his biological children to play the odds on getting a good heir. He travels with hand grenades, which he courteously offers to others. The film’s color palette could not exist in real life outside of something like Accidentally Wes Anderson. When someone gets shot or blown up, it doesn’t look too ugly. The details of the “Phoenician scheme” are kept in labeled shoe boxes. The time period is vaguely mid-twentieth century. All the men wear suits.

In one scene, Korda is on a flight with his daughter and personal tutor (Michael Cera). They will be landing soon, so he reminds them to have their passports ready. The would-be nun and the tutor both show theirs. Korda only holds his book. Liesl asks, “Where’s yours?” He explains:

I don’t have a passport. Normal people want the basic human rights that accompany citizenship in any sovereign nation. I don’t. My legal residence is a shack in Portugal. My official domicile is a hut on the Black Sea. My certificate of abode is a lodge perched on the edge of a cliff overlooking the sub-Saharan rainforest, accessible only by goat path. I don’t live anywhere. I’m not a citizen at all. I don’t need my human rights.

Liesl simply stares at him.

Here in the middle of these muted colors and fantastical plot is an observation straight out of Hannah Arendt. While so many of our countries founded their political systems on the notion of natural rights, Arendt, writing in the wake of the Holocaust and in the middle of the twentieth century, argued that the rights we experience are those guaranteed by states and citizenship. In “The Perplexities of the Rights of Man,” a chapter in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt explains: “The Rights of Man, supposedly inalienable, proved to be unenforceable—even in countries whose constitutions were based upon them—whenever people appeared who were no longer citizens of any sovereign state.” Arendt echoes Edmund Burke with his emphasis on the significance of civil rights, because she recognizes that it was when Jews became stateless that they became people without any rights.

Hannah Arendt and her mother, 1914

“The Perplexities of the Rights of Man” explores many angles of the plight of the stateless, who have no rights that anyone is obliged to observe. As she explains, “The calamity of the rightless is not that they are deprived of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or of equality before the law and freedom of opinion—formulas which were designed to solve problems within given communities—but that they no longer belong to any community whatsoever.” As we know from the Holocaust, expulsion from a political community can quickly become expulsion from the community of humanity. A man outside of political community, “a man who is nothing but a man, has lost the very qualities which make it possible for other people to treat him as a fellow-man.” Arendt emphasizes that “…the inmates of concentration and internment camps, and even the comparatively happy stateless people could see without Burke’s arguments that the abstract nakedness of being nothing but human was their greatest danger.”

In The Phoenician Scheme, Korda’s lack of citizenship and lack of human rights reflects the danger he poses to others. He does not “need” his human rights, because he has wealth and power. His “Phoenician scheme” relies on slave labor, which “is available to us.” He barely needs protection against death threats, because he survives plane crashes and bullet wounds and everything everyone throws at him.

Yet, echoing Arendt, Korda also seems to be outside the bounds of human community. He has had no real prior relationship with his daughter Liesl, who is about to take her religious vows and suspects that he killed her mother. Korda is unmoved when his employees are killed. He has had people killed. Korda keeps his nine sons in a dormitory and sees them rarely. His living situation shocks his daughter. She says “there is no love in this house. Why?” Korda exists almost only to maximize his profit. He has neither scruples nor close relationships.

Of course, The Phoenician Scheme is not a meditation on human rights and the significance of membership in the political community. Paine and Burke might both equally enjoy popcorn while watching it. Hannah Arendt might appreciate the cigarette smoking. The Phoenician Scheme may include interesting observations about citizenship, but it does not center on a significant return to political community. It does not end with a passport scene and/or a speech about civil rights and citizenship. Without saying too much, it does involve Korda’s return to the human community, largely led there by his daughter. Perhaps somewhere on that journey she also took him to the passport office.

Elizabeth Stice is a professor of history at Palm Beach Atlantic University. She has a book about World War I, Empire Between the Lines: Imperial Culture in British and French Trench Newspapers of the Great War, and she has written for various publications, including Front Porch Republic, Comment, and Inside Higher Ed. She is editor in chief of Orange Blossom Ordinary.