Is Liberalism Dead? Part II

Part I of this essay is available here.

The gnostic impulse to transcend limits has deeply shaped American progressivism, which believes not only in the malleability of society but also in the malleability of human nature itself. Gnostic liberalism has thus reoriented the goals of liberalism: it is no longer about preserving individual liberty and equality within a community of traditions but about reconstructing society—and human nature—around a vision of unrestrained self-actualization.

Consider the realm of human nature. Prior to the mid-twentieth century, liberalism's focus on the individual was balanced by a sense of inherited duty and obligation. Individuals were autonomous, but their autonomy was shaped by their embeddedness in a web of relationships—to family, community, and even a higher law. Today, gnostic liberalism has birthed what I call the "imperial sovereign self." Unconstrained by any external authority, individuals become self-made deities, empowered to fashion their own nature according to their will.

Nicolas-Sébastien Adam, Prométhée enchaîné (1762)

This radical vision of self-sovereignty not only elevates the individual but also deconstructs social bonds. Commitments to family, religious institutions, and communal responsibilities are seen as limitations to self-actualization. Personal liberation requires dismantling these structures, perceived as relics of an oppressive past. This "identity trap," as I explore in "The Identity Trap and the Dangers of Gnostic Liberalism," leads individuals to believe they must break free from any predetermined or inherited identities, viewing them as shackles rather than vital sources of meaning and belonging.

Yet, this conception of autonomy is both unstable and self-destructive in its rejection not only of inherited forms of meaning but also the very ties that give the self depth and substance. In rejecting family, faith, and community, gnostic liberalism isolates individuals, leaving them vulnerable to manipulation and coercion. With traditional sources of moral and social guidance replaced by an ideology that values only the will of the self, society finds itself adrift without enduring standards of right and wrong, guided only by the subjective whims of individuals.

The influence of gnostic liberalism extends beyond individual identity to reshape society itself. The gnostic emphasis on self-creation and autonomy, combined with liberalism's commitment to emancipation, has produced what Roger Scruton called a "culture of repudiation." Every tradition, custom, or norm is now seen as potentially oppressive, something to be critiqued or discarded. According to Scruton, such a cultural climate would encourage constant defiance of boundaries and limits, creating a society where any established norm—whether rooted in religious, cultural, or biological grounds—is subject to redefinition.

Previously, liberalism's desire to liberate the individual from constraints was tempered by recognition of the need for social order and the role of institutions in transmitting values across generations. Today, however, the gnostic drive to transcend traditional limits rejects these restraints, leading to a dismissal of societal boundaries and the conventions that uphold them. This erosion of norms leaves society vulnerable to instability as the shared foundations that once provided social cohesion are increasingly undermined in the name of personal liberation.

The convergence of liberalism and gnosticism has fundamentally reshaped our political landscape. Once tempered by the influence of tradition and gradual reform, liberal meliorism—the belief in incremental social improvement—has morphed into a utopian quest to perfect the human condition and social order. This shift echoes Eric Voegelin's famous warning against the desire to "immanentize the eschaton"—to attempt to realize a perfect world within history.

Gnostic liberalism distorts liberalism's earlier, pragmatic spirit. Instead of seeking steady improvement within the framework of tradition, gnostic liberalism aspires to create a new reality where traditional distinctions are eradicated. Even human nature itself is subject to this transformative vision. For the gnostic liberal, humanity can and should be "perfected" through technological, social, and even biological engineering.

Robert P. George discusses this in The Clash of Orthodoxies where he critiques the hubris of believing society can engineer moral and social perfection. George emphasizes that such attempts often lead to coercion and the suppression of dissent, as the envisioned utopia allows no room for alternative viewpoints.

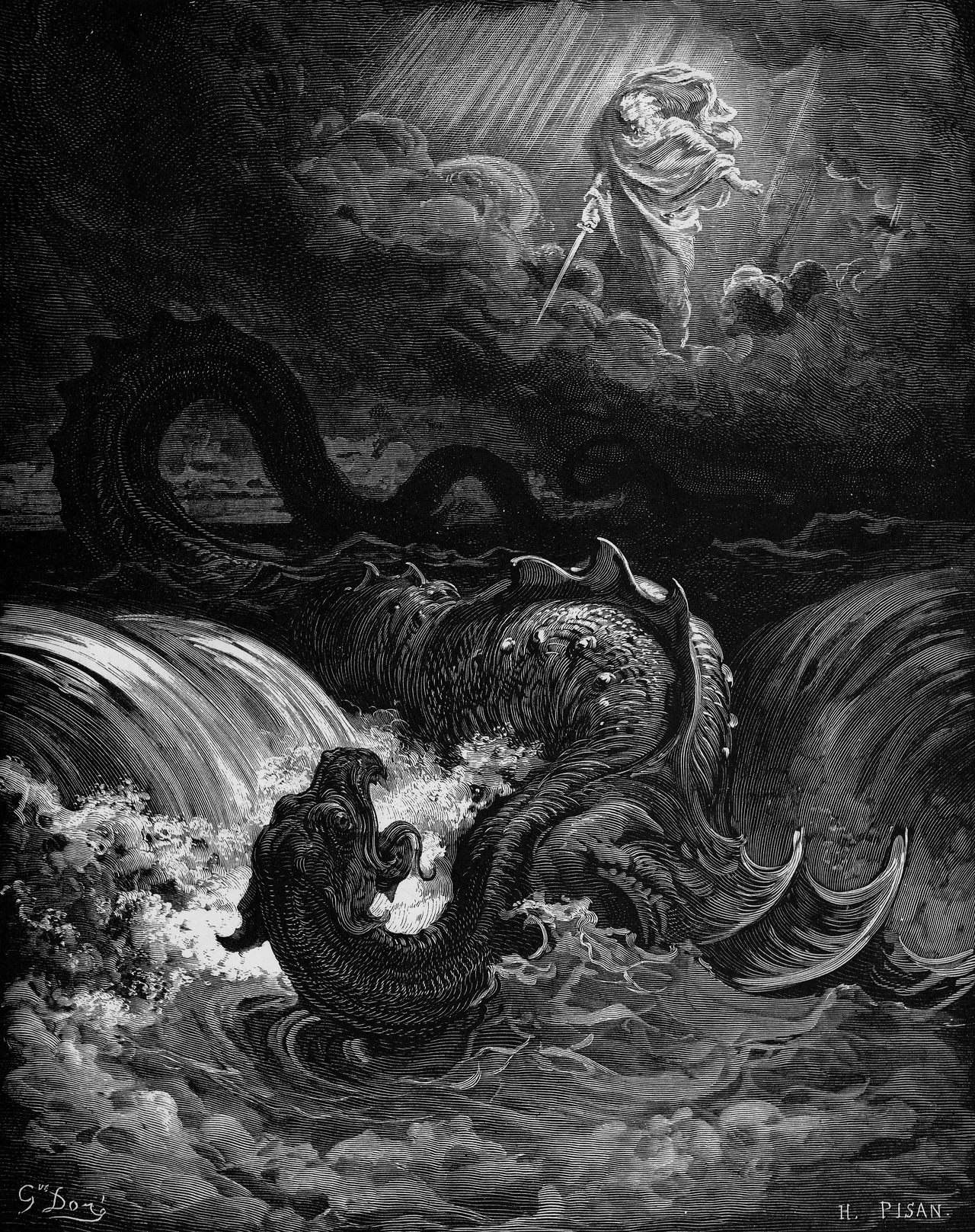

Gustave Doré, The Destruction of Leviathan (1865)

How is this secular utopia to be achieved? Here, the gnostic liberal vision converges with the ambition of a self-appointed elite—a "vanguard" that believes it possesses the insights necessary to engineer a just society. As I’ve argued before, this "gnostic elite" is a group that considers itself enlightened and empowered to reshape society according to its own ideals. It justifies the use of state power to enforce its vision, seeking to dismantle traditional social and political institutions in the name of perfected justice.

I’ve described this dynamic as a kind of "gnostic Leviathan," where the state, acting as an instrument of the enlightened few, exerts unchecked authority to impose a reconstructed social order. The result is absolute power, unconstrained by the very values of limited government, individual rights, and tolerance that once defined liberalism. Rather than fostering a pluralistic society where differing views coexist, the gnostic state increasingly insists on conformity to its vision, treating dissent as an obstacle to progress.

To return to the original question: is liberalism dead? We are not witnessing the end of liberalism but a transformation driven by an ideological distortion—one that has abandoned the traditions and limits that once tempered its ambitions. The answer is not to abandon liberalism, but instead to recognize and resist the gnostic tendencies that distort liberalism and restore its core values: limited government, individual liberty, and respect for tradition. By grounding individual liberty within a framework of tradition and shared moral order, we can restore the balance that once made liberalism a constructive force. In doing so, we not only safeguard the achievements of liberalism but also ensure its vitality for the challenges of the future.

Andrew Latham is a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College. He is also a Senior Washington Fellow with the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy and a Non-Resident Fellow with Defense Priorities—both think tanks in Washington, DC.