The Diverse Roots and Routes of Liberty

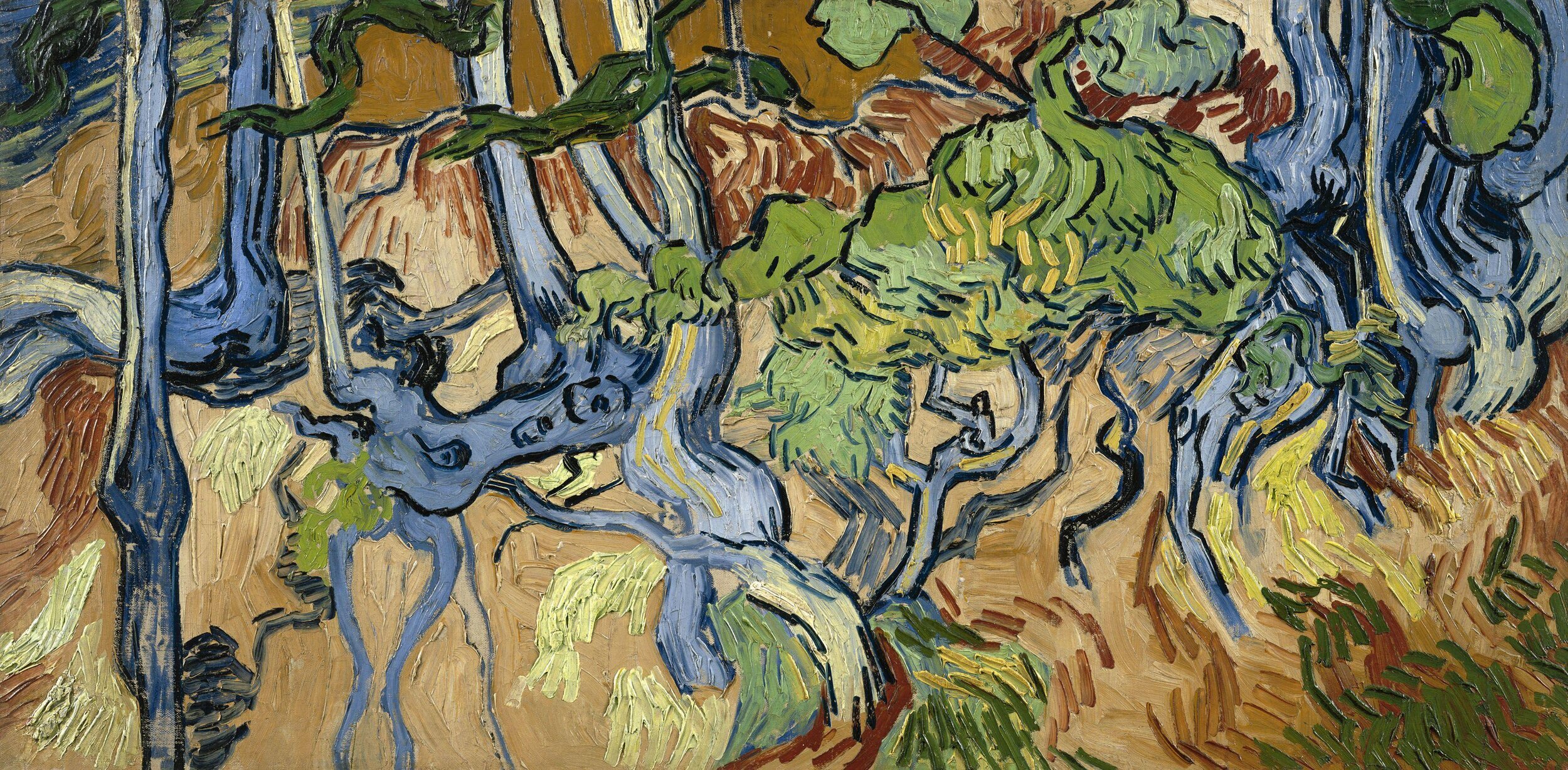

Tree Roots and Trunks by Vincent van Gogh

The off-liberal complicates a narrative of “liberalism” as some teleological process of radical autonomy. The off-liberal instead notes a variety of sources for the institutions, practices, and ideas associated with the “liberal” order. It also reveals the ways that various elements of the “liberal” tradition can themselves undercut a teleology of autonomy. In developing some of the alternative pathways of the off-liberal, I would like to highlight three of its modes: noting certain practical sources (outside ideological liberalism) for elements of the “liberal” order, exploring intellectual accounts of modern liberties that do not rely on some claim to radical autonomy, and highlighting the way that figures in the “liberal” tradition can challenge the project of atomistic autonomy.

Limits on centralized power and protections for personal rights are often taken to be hallmarks of the “liberal” order, but their origins cannot be traced to liberal theory. Consider for instance the practice of mixed government. While the dispersal of power is often taken to be essential for a “liberal” state, the mixed regime itself goes back thousands of years. Aristotle discussed it in The Politics, and the historian Polybius spoke favorably of such a regime in his analysis of ancient Rome. As Jacob Levy has explored in Rationalism, Pluralism, and Freedom, the heterogeneous web of institutions that constitutes civil society (another central “liberal” concept) and checks centralized power can be traced at least to the Middle Ages. The legacy of these medieval institutions was central to the work of many thinkers in the “liberal” tradition (such as Montesquieu). While various liberals might have offered a justification for the mixed regime or checks and balances, the precept of limiting unitary power long predates their theorizing.

More broadly, other principles often grouped in the “liberal” tradition can find justifications quite different from radical autonomy. In his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, Leo XIII defended protections for private property (another tenet long associated with liberalism) not with a reference to John Locke or Adam Smith but Thomas Aquinas. By embedding the person in a wider set of human relations, Leo recast these protections in terms of social obligation: “Whoever has received from the divine bounty a large share of temporal blessings, whether they be external and material, or gifts of the mind, has received them for the purpose of using them for the perfecting of his own nature, and, at the same time, that he may employ them, as the steward of God’s providence, for the benefit of others.” This enterprise of ownership as stewardship for the greater good offers one view of how protections for private property could be justified not as part of some relentless quest for radical autonomy but instead as involving a personal duty to serve a broader common good.

Pope Leo XIII

This attention to the common good also led Leo XIII to emphasize the importance of government regulation—of working conditions, for instance—and cooperative bargaining units to help protect the working class and the virtue of society as a whole. Leo argued that the socialists of his time called for policies that threatened both the worker (by lessening the rewards of work) and the family (by setting up an invasive state that would “destroy the structure of the home”). Leo’s attention to the common good, then, offered a justification for a kind of regulated market economy.

That sense of liberty-via-obligation can be found in other sources, too, and can help to globalize an account of liberty’s resources. The ancient Confucian thinker Mengzi stressed the importance of the rulers serving the people and implied that a ruler who violated the principles of benevolence could be justly overthrown. While this is far from an endorsement of democracy, it does cut against certain doctrines of absolutism. A king’s power depends upon his serving a deeper purpose and ruling his people well. Moreover, the importance of human flourishing and embedded connections for Mengzi and other Confucian thinkers is also compatible with some contemporary accounts of “liberalism” that premise a liberal political order on the idea of a commitment to human dignity. Martha Nussbaum, for instance, has appealed to the importance of concrete human commitments in order to show the importance of Rabindranath Tagore’s work for liberal life.

All of this suggests numerous practical sources for some of the institutions of modern liberty as well as intellectual justifications for them. Moreover, even figures who are sometimes taken as leading “liberal” thinkers might challenge the conventional narrative of liberalism as autonomy. With his opposition to cruelty, Michel de Montaigne plays a key role in Judith Shklar’s “liberalism of fear.” Yet Montaigne’s model of the self is in tension with the conventions of liberalism as autonomy. If “liberty” is fundamentally about the rule of the autonomous will, Montaigne’s account of the person as thoroughly opaque troubles that project of autonomy.

Michel Montaigne, Artist unknown.

In his apology for Raymond Sebond, Montaigne stressed “the confusion that our judgment gives to our own selves, and the uncertainty that each man feels within himself, that it has a very insecure seat.” For Montaigne, it’s not merely that our opinions are inconstant—the operations of our selves remain cloaked in mystery. His essay “How the Soul Discharges its Passions on False Objects When the True Are Wanting” finds that we will divert our energies to some available object in the effort to fulfill some deeper need. Montaigne referenced Plutarch’s claim that people whose “loving part” lacks “a legitimate object” will instead lavish affection on pets: “the soul in its passions will sooner deceive itself by setting up a false and fantastical object, even contrary to its own belief, than not act against something.” That passionate display of affection for a pet, Montaigne claimed, is a refracted desire for a deeper kind of love; we do not always see clearly what we ourselves really desire.

Montaigne declared at the outset of his essays, “I am myself the matter of my book,” but the project of his essays as a whole is premised on the notion that it takes great imaginative trial and experimentation to explore this self. This “self” is not transparent to some absolute will. Looking inward, a person cannot immediately diagnose what she really wants and set her will to realizing this end. Habit, circumstance, and impulse shape that self and its responses. For this model of personhood, the ideal of some self-authorizing autonomous will might seem fraught to the point of incomprehensibility.

Montaigne’s point about the messiness of the inner person might be revealing for another aspect of the off-liberal, too. The off-liberal scavenges for eclectic insights, pursuing oblique paths in the hopes of getting a better view of the whole. Rather than imposing some reductive (and illusory) comprehensiveness or dissipating itself in endless fragmentation, the off-liberal mounts a continued dialogue between part and whole. Many modern (though not only modern) accounts of the person have emphasized the idea of inner uncharted depths. Those depths give a person substance and the possibility of internal surprise; they simultaneously frustrate and incentivize the project of introspection. The off-liberal takes a similar approach to political ideas and structures. By resisting reductive narratives and hunting through disparate sources, it can reveal the many textures of freedom.

A Print from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress 1813. The British Museum

This brief survey of some of the off-liberal’s alternative paths indicates how an emphasis on care, duty, and solidarity—and not mere isolated autonomy—can find virtue in the practices of modern liberty. The various networks that constitute civil society (and prove so essential in restraining centralized state power) are in part forged through human commitments. Leo XIII saw in a regulated market economy the opportunity to defend the formation of families and advance the cause of personal dignity through stewardship. In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville based the exercise of American democracy not on the search for radical autonomy but instead on the organic commitments of community. Resisting individualisme and encouraging participation in cooperative social endeavors were essential for checking the rise of a velvet-gloved autocracy.

There are many roads to modern liberty, but some of those routes focus not on the triumphant will but instead on the richness of the person and our commitments to one another.

Fred Bauer (@fredbauerblog) is a writer from New England.