Retelling the Human Story

In the previous part of this essay I argued that the crisis of historicism in the early twentieth century can also be understood as a crisis of deep history, when advances in science presented a disconcerting problem for our understanding of the story of our species. Sacred histories suddenly appeared too short, but no plausible replacement was readily apparent. This caused a modern identity crisis which was related to, though distinct from, the better-known historicist problem of moral relativism. While Daniel Lord Smail has recently argued that we remain in the grip of sacred history, it is important to recognize that theologians and philosophers have themselves been coming to terms with the long history of our species, our planet, and our universe for at least as long as geologists and biologists have been aware of it.

In the early twentieth century, Ernst Troeltsch offered the most celebrated diagnosis of historicism’s crisis and also mooted important solutions to it, but we will begin before Troeltsch, with Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche was a precursor to Troeltsch who wrestled with many of the same problems, though to quite different ends. The two were literally read alongside one another by philosophical students of historicism. In Max Frischeisen-Köhler’s 1907 anthology Moderne Philosophie, two excerpts were included in the section devoted to historicism: one from Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, and the other from Troeltsch’s recently published The Absoluteness of Christianity and the History of Religions.

In 1873, shortly after writing The Birth of Tragedy and as he was beginning to compose and publish the essays that would make up his Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche wrote an essay titled “Truth and Lying in an Extra-Moral Sense.” It remained unpublished until close to his death, and it offers a tantalizing theory of truth that foreshadows his later work, his unique approach to moral philosophy, and his critiques of intellectualism. Nietzsche begins his essay with a disturbing parable:

Friedrich Nietzsche

In some remote corner of the universe, flickering in the light of the countless solar systems into which it had been poured, there was once a planet on which clever animals invented cognition. It was the most arrogant and most mendacious minute in the “history of the world”; but a minute was all it was. After nature had drawn just a few more breaths the planet froze and the clever animals had to die. Someone could invent a fable like this and yet they would still not have given a satisfactory illustration of just how pitiful, how insubstantial and transitory, how purposeless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature; there were eternities during which it did not exist; and when it has disappeared again, nothing will have happened.

Nietzsche’s description is more poetic than scientific, but the absorption of human history into a much wider stretch of time anticipates Daniel Lord Smail’s more recent attempt to demythologize sacred history. Unlike Smail, though, Nietzsche goes on (in this essay and in his entire writing career) to focus on the implications of these historical depths for human dignity and agency. This early essay offers an extremely negative picture of what one should expect from a history beyond sacred history: nothing will have happened. Under what metaphysical assumptions, though, would one be able to say that at the end of life and existence, nothing was? Here Nietzsche is perhaps being hyperbolic, and it would be wrong to accuse him of having no theory of an adequate human response to this situation. Quite the opposite: deep history for Nietzsche means that history must be made to serve life rather than vice versa. We must take hold of our moment in the world and love our fate (amor fati). What Nietzsche rejects is the significance of our idealisms, which are mere projections of sickly intellect upon reality.

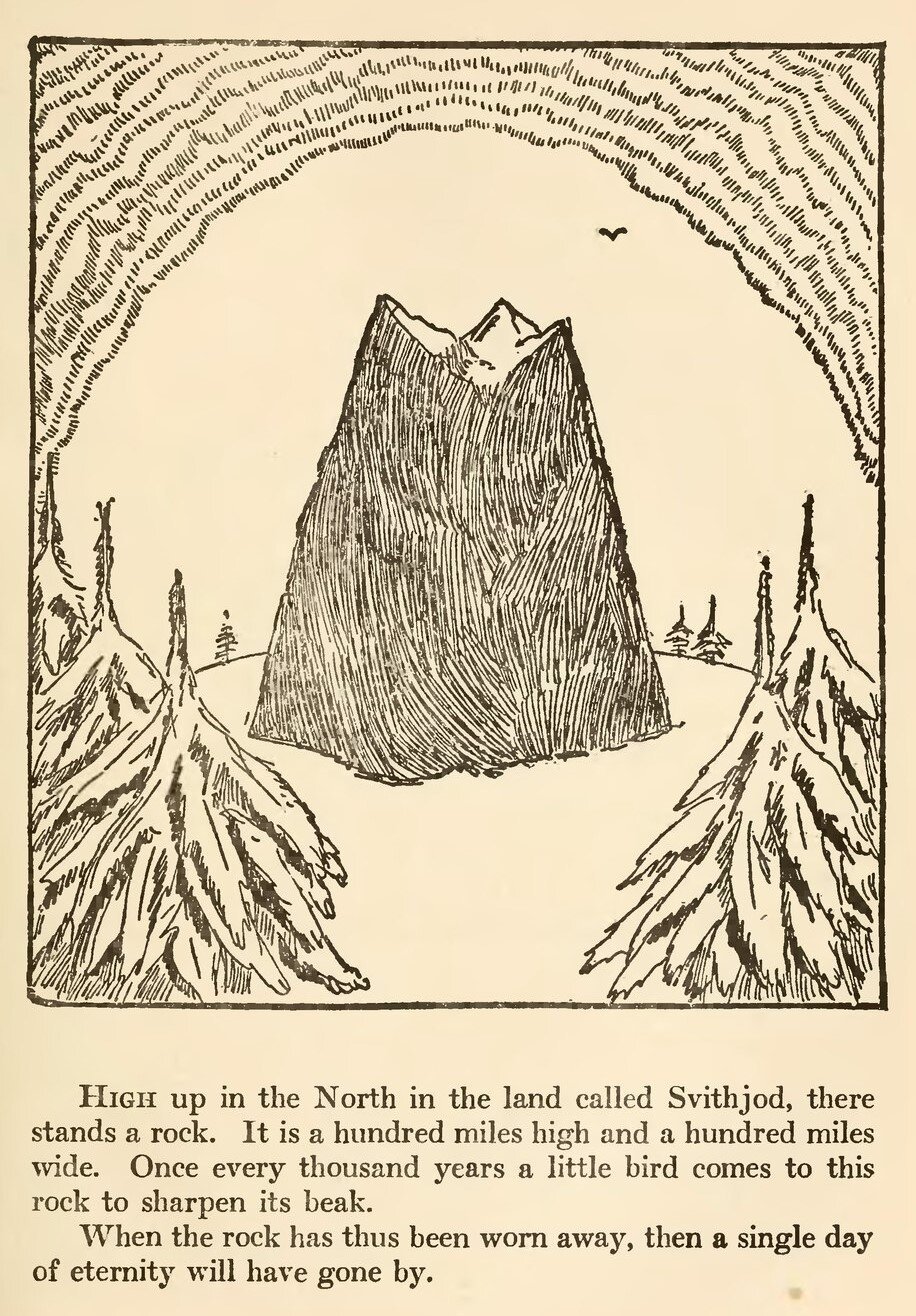

Nietzsche perhaps captured an anti-humanist mood running alongside the nineteenth-century time revolution, but he did not offer a philosophy that was very digestible for the reading public. A very different attempt to illustrate history in all of its depth, and one that did penetrate the consciousness of a generation, comes from the Dutch-American author Hendrik Willem Van Loon. His award-winning children’s book The Story of Mankind (1921) conformed, in large part, to the civilizational focus that Smail calls sacred history, beginning with ancient cultures of the Nile Valley. At the same time, Van Loon was attentive to evolutionary scale. He notes that human history only amounts to a small portion of the entire length of animal life on earth, and prefaces the story of mankind earlier in evolutionary history. An opening reflection steps back even further, to a mythological account of deep history:

High up in the North in the land called Svithjod, there stands a rock. It is a hundred miles high and a hundred miles wide. Once every thousand years a little bird comes to this rock to sharpen its beak.

When the rock has thus been worn away, then a single day of eternity will have gone by.

Van Loon’s Svithjod is a stark edifice, reminiscent of Buddhist and Hindu legends about the length of a kalpa, or eon. He manages to paint a picture equally as stark as Nietzsche’s minute of animal cleverness on an otherwise frozen planet. And this in a children’s book! However, Van Loon’s humanism is nothing like Nietzsche’s critique. The scope of the human story may fit within a single day of eternity, but more than nothing happens in that story. Sacred histories of great civilizations may remain to be exorcised from historical studies, then, but the long cosmological vision that stands at the foundation of deep history has been used as a way to frame, humble, and offer perspective for shorter chronologies. At the turn of the twentieth century in particular, deep time became a point of sublime fascination for philosophers as well as the broader public.

Troeltsch, of course, was alive to these concerns and almost single-handedly introduced the worrisome shrinking of human significance amidst new conceptions of history and cosmos as a matter of vital importance for modern Protestant theology. In the last essay we encountered his image of being swept into a vortex and facing an alienating boundlessness. In his Heidelberg theology lectures from the early 1910s, Troeltsch described a similar problem to his students, but framed it in terms of the deep future—of eschatology as best forecasted in light of contemporary scientific discoveries:

Hendrik Willem Van Loon

Wave after wave of human history has come and gone—we cannot reduce the future as a whole to our own future. But what will the end be like? Presumably a diminution of the sun's energy, accompanied by increasing difficulty in obtaining food, until finally the last human being roasts the last potato over the last glowing ember—and that only if all three of them somehow manage to get together. This is now a customary picture of the end.

Troeltsch goes on to reject, on the basis of this cosmological pessimism, the naïve modernist optimism of a continuously progressive ethical kingdom of God, saying, “In light of such future possibilities, there can be little hope for a millennial kingdom, to say nothing of how little comfort such a kingdom would really offer. The sufferings of the past will not be mitigated by the hope that things will get better after the passage of a few centuries.” Troeltsch was alive to the delicacy of sacred history in light of cosmological and geological scientific advances, and at the very least he successfully challenged traditional apocalyptic metaphors as inadequate to the scope of historical time and the distant end of the world.

The rise of modern evolutionary biology and geology was far from Christianity’s first encounter with the challenge of fitting into a very old universe. The doctrine of the eternity of the world inherited from Aristotelian philosophy was a topic of dispute for medieval scholastics, and encounters with world religions throughout Christianity’s history meant that religious theories of past eons were available. Unique on the agenda for early twentieth-century historians, philosophers, and theologians, though, was the challenge to build a human story outside of the biblical chronology, in the crisp and indifferent climate of the distant past as captured in modern quantitative measurements. The scratch from which these writers work is captivating in its simplicity, like the spare sketches of Van Loon’s history book.

Equipped with little but a post-humanist awareness that displaces humanity as the measure of all things, these writers wrestled with the fact that our role in the universe is vertiginously small and rests on no particularly obvious cosmic architecture. And yet, here humanity is, and will be for at least a little while. Nietzsche believed that the idealist’s cogito was laughable as a ground for human dignity, and in contrast he proposed a categorical imperative: to live every moment with a will to its eternal recurrence. Troeltsch, likewise, saw only pessimism and nihilism in any account of the human that does not adjust itself to the new chronology. The crisis of deep history really was a crisis for our modern self-understanding, and a short chronology of human civilization is no longer adequate for explaining our place in the world.

Evan F. Kuehn is Assistant Professor of Information Literacy at the Brandel Library, North Park University. His research focuses on 19th-20th century Protestant thought, as well as topics related to knowledge organization.