The Crisis of Historicism as a Crisis of Deep History

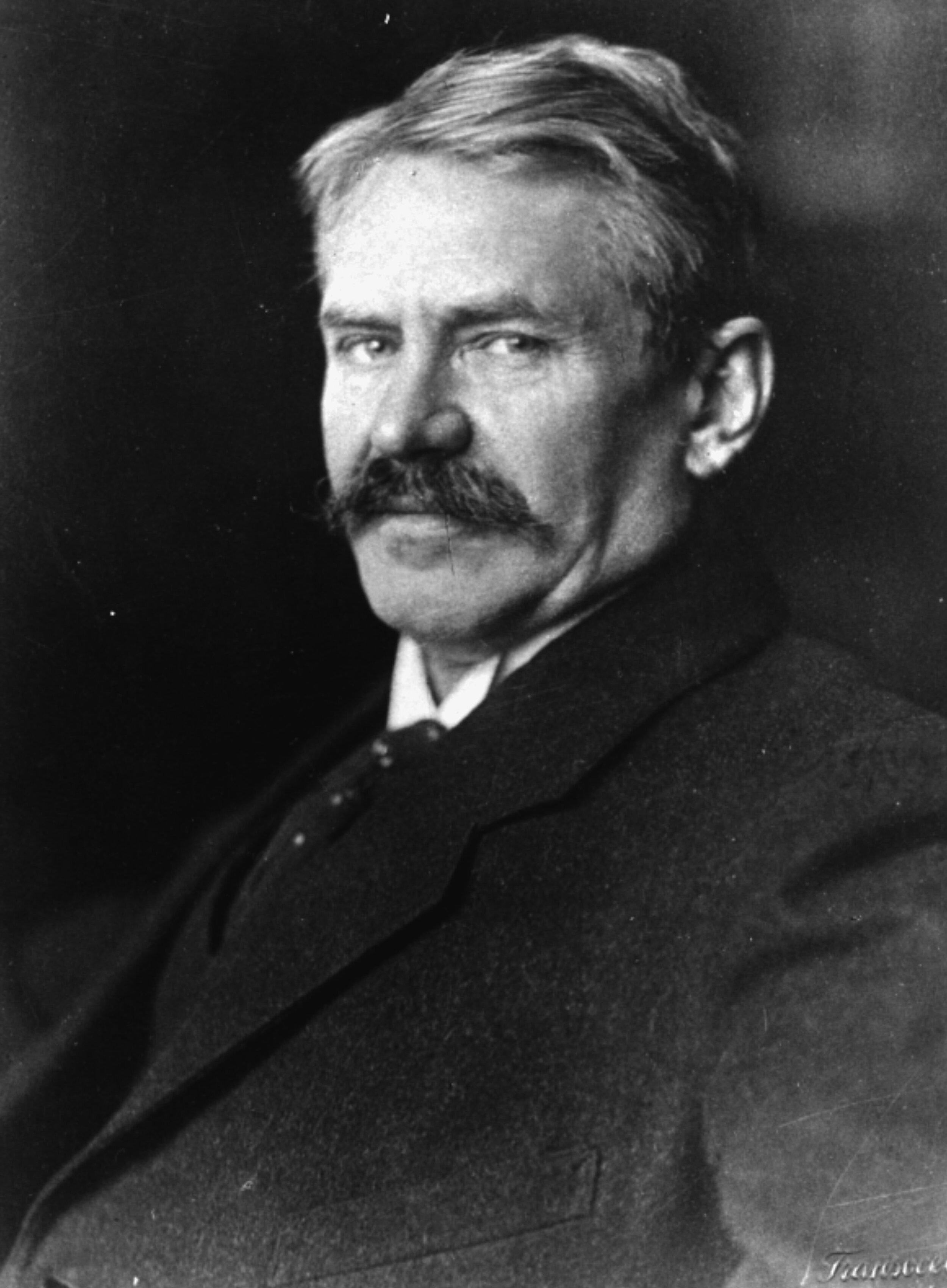

Ernst Troeltsch

In recent decades, a recognition of the immense temporal scope of past and possible human experience has informed a concerted agenda in the humanities. The concept of the “Anthropocene,” for instance, has sought to map human history alongside epochal geological time scales and recognize the emerging human impact upon natural history. While the Anthropocene could be described as a theory of our modernity—its beginning sometimes marked as recently as the Industrial Revolution—the premise of the Anthropocene is that our species is a geological, climatological, and evolutionary force that extends beyond human history as civilizational history.

In his On Deep History and the Brain, Daniel Lord Smail presents an apology for “deep history,” which considers the human at the level of the Anthropocene rather than many of the narrower frames of reference that we are used to. By “deep history,” Smail means the inclusion into historical research of Paleolithic humans. Although the advances in our understanding of geological time that are necessary for deep history have been available to the scholarly world since the mid-nineteenth century, Smail argues that we have remained in the “grip of sacred history,” and that this has prevented us from thinking about history beyond current conceptions of civilization:

For several thousand years, historians writing in the Judeo-Christian tradition were untroubled by this question of origins. Sacred history located the origins of man in the Garden of Eden, and that is where the general histories of late antiquity and medieval Europe began the story. In the eighteenth century, proposals for shortening the chronology proper to general history began to circulate, as the new fad for catastrophism brought historical attention to bear on the Universal Deluge. […] On the heels of the time revolution of the 1860s, historians gradually came to accept the long chronology as a geological fact. But we have not yet found a persuasive way to plot history along the long chronology, preferring instead to locate the origins of history at some point in the past few thousand years.

Secularized versions of this beginning may point to Egypt or Mesopotamia as the supposed beginning of civilization, but the originally Abrahamic restriction of history to a chronology of a few thousand years remains—and this despite knowledge of a much longer human presence on earth, and of the earth itself before the rise of Homo sapiens. “By the early twentieth century,” Smail writes, “most professional historians had abandoned sacred history. Yet the chronogeography of sacred history and its attendant narratives of rupture has proved to be remarkably resilient. History still cleaves to its short chronology.” Increased knowledge of our galaxy’s place in the universe through the first half of the twentieth century could also be included in this rapid expansion of scope with which historians have had to contend.

What is interesting about Smail’s proposal is the way that he leverages an argument for a radically longue durée approach grounded in evolutionary and neurobiology by means of an opposition to sacred history. The inertia of the influence of sacred history that he identifies in historical studies is surely accurate. But its resilience is not simply the result of a naïve religious public. Sacred history remains because deep history has always struggled to capture the imagination of our human identity. The ill fit between modern forms of knowledge and premodern frameworks of understanding has often generated these crises.

In the early twentieth century, the liberal Protestant theologian Ernst Troeltsch coined the term Krise des Historismus. Following the blossoming of modern historical sciences in European research universities, the crisis of historicism was a recognition of how destructive the modern consciousness of our historical situatedness could be for any assertion of universal moral principles or a more traditional religious explanation of the human being. The disruptive rise of historicism also marked the beginning of an anti-historicist backlash that manifested itself in both revolutionary and reactionary forms. The crisis, for historicism, was its inability to hold together a single human story in the wake of its demolition effect on older sacred narratives.

The historian Herman Paul has noted that the crisis of historicism was not merely a theoretical dispute vexing German academic elites, but rather a disturbing shift in consciousness for working-class, religious, and other communities as well. The crisis threatened the bonds that used to hold between one’s life and one’s heritage. While historical faculties discussed the crisis in rarified form, then, anyone whose sense of self was deeply entwined with the past felt the impact of the historicist’s predicament.

Usually this fin de siècle crisis is understood as a strong acid degrading our sense of universal moral values. With no unbroken chain across centuries and continents to validate an assurance of ultimate stability, we are left with a hapless relativism. Ernst Troeltsch unpacked the malaise more perceptively than anyone, often referring to metaphors of flooding waters overtaking our sense of coherence. At the turn of the twentieth century, he spoke of being “swept into the vortex; there is no unchangeable code of conscience any more,” and of “horror in the face of the alienating and relativizing boundlessness of the fragile conditions of existence.” In the crisis of historicism, modern European society saw how unsteady the ground beneath its feet really was.

What if, in light of current discussions about deep history, we were to reconceive the modern anxieties surrounding the crisis of historicism to include more than simply the already-familiar fragmentation of the moral self? On the cusp of a new century, Europeans also saw that we dwell in a vertiginously large, and seemingly mostly empty, temporal landscape. The crisis of historicism was a crisis of deep history facing, with the eighteenth-century geologist James Hutton, the sense that we are left with “no vestige of a beginning—no prospect of an end.” During the nineteenth century, new theories of evolution and research on past ice ages disrupted the centrality of scriptural origin myths that had framed our sense of common history, but also involved them. “That man was not in all the earlier ages of the world, except in these prophecies of his coming, geology assures us,” wrote the anti-Darwinist geologist John William Dawson in his 1888 The Chain of Life in Geological Time. Dawson went on to argue for a recent (post-glacial) appearance of humanity on the basis of widespread ice age extinctions. Debates between catastrophism and uniformitarianism therefore coalesced with theological discussions of the advent of our species, even amongst geologists themselves. In the twentieth century we see a refinement of available chronological data. The discovery of and research on radioactivity in France and the subsequent development of radiometric dating technologies brought precision to our measurement of deeper histories. All of these advances in the natural sciences ought to be recognized alongside the monumental historical research programs of von Ranke, Burckhardt, and others as pushing modern European society toward a crisis of consciousness about its place in the world.

Ernst Troeltsch was alive to these concerns and insisted that we not isolate the religious implications of the modern natural sciences from those of the historical sciences. In a lecture to his students, he once chided, “Theologians all too readily forget the skepticism that overwhelms the modern person who contemplates the immeasurable vastness of time. According to the unanimous opinion of scientists, our planet has existed for three million years!” Troeltsch here actually offers an extremely low estimate for the age of Earth even given his own historical context: scientists had been talking about a planetary age of tens or hundreds of millions of years throughout the nineteenth century. Since Troeltsch’s lifetime, these estimates have been likewise dwarfed by current scientific consensus of planetary age of 4.54 billion years. Even in recognizing the outpacing of theological intuitions by scientific research, then, Troeltsch sometimes failed to keep up!*

Herbert Ponting's photograph Grotto in an Iceberg (1911)

How do we begin to place ourselves within deep history? Or rather, how did we begin to do so? If Smail is correct to recognize that a short chronology continues to hold sway in our not-so-modern understanding of the human being, it would be wrong to conclude from this that theologians and philosophers have been idle in engaging with the problem. In Part II of this essay, I will substantiate the claim that the crisis of historicism was, in part, a crisis of deep history by highlighting literary efforts to place the story of human history within its long chronology.

*Note: This paragraph has been slightly modified from a section that appears in the conclusion of my book, Troeltsch’s Eschatological Absolute (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Evan F. Kuehn is Assistant Professor of Information Literacy at the Brandel Library, North Park University. His research focuses on 19th-20th century Protestant thought, as well as topics related to knowledge organization.