We Are What We Behold

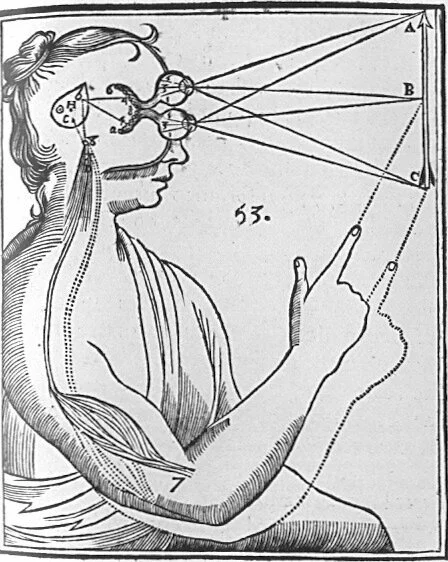

A woodcut from Descartes' 1644 Principles of Philosophy

“Behold.” It’s a word with a slightly archaic, formal flavor, one we might associate with old hymns or the traditional cadences of the King James Bible: “for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people . . .” It’s easy to forget that it was once an everyday word meaning simply “look" or “see" and that it generally carried no more special gravitas in its use than its modern equivalent “look” does for us today. The very structure of this word, however, reflects an ancient explanation of the phenomenon of sight which—like the word itself—has quite recently dropped out of the modern imagination.

As you might guess just from looking at it, “behold” comes from the same etymological root as the verb “hold,” and initially the prefix “be-” simply strengthened the root word to make it mean “grasp” or “retain.” The application of this strongly tactile verb to the realm of sight—such that “grasp” becomes “observe” or “gaze”—fits a long-standing theory of sight that has only been displaced by the advent of modern ophthalmology.

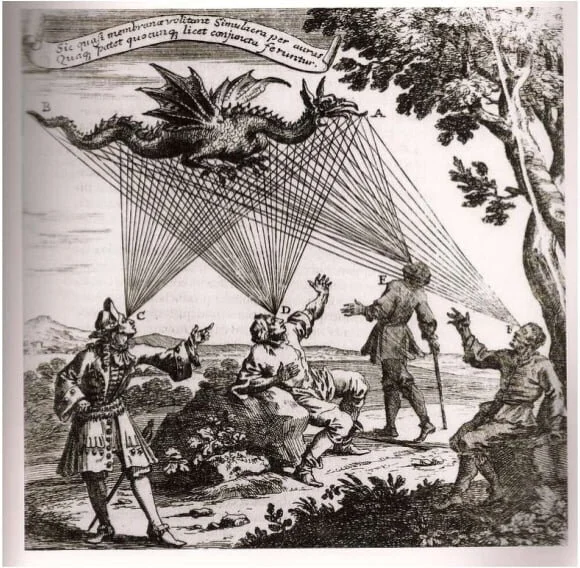

Today, we know that sight is made possible when photons from a light source bounce off the object of our sight and into our eyes, delivering the information necessary for our brains to construct a reasonably accurate image of what we are seeing. Up until at least the eighteenth century, however, most people believed that the light rays required for sight originated from the eyes themselves. These light rays were understood literally to shoot out from the eyes, travel to the perceived object, physically pick up a tiny imprint of that object, and then finally carry that imprint back to the eye along the same ray with which the process started. In this way, every time an individual looked at an object, a tiny version of that object was physically imprinted on the eye’s receivers.

This theory of sight corresponds to the ancient avoidance—still common in many cultures—of the gaze of certain persons or powers. Take the tale of the Gorgon, the snake-haired woman who turned to stone those who looked into her eyes. Sight in this context does not involve simply a passive, receptive stance, but indeed an active, tactile interaction between the viewer and the viewed. The myth of the Gorgon captures the idea that being seen involves a real, physical vulnerability to the penetration of the other—even without any literal touch involved.

The head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens

What is more, as this tale highlights, sight is in the ancient understanding a mutual interaction in which one both reaches out to “grasp” the object of sight with the eyes and is simultaneously grasped by that object. And this is not only the case when the object of sight is itself an agent with eyes of her own, like the Gorgon. Rather, because the viewed object’s image remains physically imprinted on the viewer’s eyes and memory, even an inanimate object maintains a certain power over the viewer to change and to shape him—sometimes indelibly. Various ancient authors reference the “Gorgon effect” to warn their readers that in some sense we always become what we behold.

Take Philo, a first-century Jewish philosopher who was equally well-versed in Greek mythology and the Bible. As part of an embassy sent from Alexandria to request protection from the emperor Caligula for the Jews living there, Philo and his fellow diplomats found themselves needing to explain why they did not want a statue of the emperor erected in their Temple at Jerusalem. By way of explanation, they reference the myth of the Gorgon:

We have heard a very ancient tale, handed down throughout Greece by learned men, who affirmed that the head of the Gorgon had such great power that those who looked upon it immediately turned into stones and rocks. This story is, no doubt, a figment of myth, but . . . do you suppose (may it never be!) that if any of our own should see this statue being escorted into our temple, they would not be changed into rocks, their joints frozen, and their eyes too, so that they might not even be able to move, their entire bodies—every part and system—losing all their natural motions?

Here, Philo suggests that those who are forced to behold an idol against their conscience will be quite literally turned into one themselves. It’s a clever use of Greek mythology turned against the Romans, who prided themselves on their cultural appropriation of all things Greek. While we probably don’t find the literal meaning of his argument to be that convincing (and, arguably, he would never mean us to), his hyperbolic language does point to the same idea we have already been considering—one is always shaped by what he beholds.

Other ancient authors, like Plato in the Phaedrus, give the Gorgon effect a more positive spin in the context of the contemplative, religious gaze:

When [the followers of Zeus] search eagerly within themselves to find the nature of their god, they are successful, because they have been compelled to keep their eyes fixed upon the god, and as they reach and grasp him by memory they are inspired and receive from him character and habits, so far as it is possible for a man to have part in God.

This idea of the mimetic effect of theophanic vision gains a significant afterlife in early Christianity and especially Christian mysticism. In the fourth century AD, Gregory of Nyssa neatly summed up both the positive and the negative potential of the Gorgon effect from the Judeo-Christian perspective:

For just as those who look to the true godhead receive in themselves the unique features of the divine nature, so too, the one who devotes himself to the vanity of idols is transformed into that upon which he looks, becoming a stone instead of a human being.

Today, partially because of our improved understanding of the science of vision (but also perhaps due to other factors), we have in many ways lost the ancient reverence for the mutual inter-penetration that happens when we view an object. Perhaps an appreciation for our vulnerability to be shaped and even permanently marked by the things at which we look might cause us to reconsider some of the objects we regularly place before our eyes. There are numerous studies, for instance, pointing to the lasting negative effects of viewing violent acts even from the apparent unreality offered by a screen. And on the more positive side, when we think of wanting to cultivate virtues, we often don’t consider the powerful effects of well-chosen objects of our vision. We forget the degree of autonomy we have in choosing the objects upon which we fix our eyes— objects we will seize on and be seized by.

Johann Zahn - Emission Theory, “Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium”, 1685

While the ancients may have had the science wrong, the reality of the experience to which they referred by the “Gorgon effect” still rings true today. The word “behold” may have fallen out of our vernacular, but the idea it captures of the active experience and lasting effects of sight may still be worth holding onto.

J. LaRae Cherukara is a PhD candidate at the University of Oxford, writing her dissertation on images of grace in Greco-Roman, Jewish, and early Christian writings of the first century. LaRae lives with her husband at a boarding school in the English Midlands.