Modernity in the Balance

One purpose of historical inquiry, particularly genealogical approaches, is to reveal the contingency of concepts, norms, or patterns of life that are assumed to be universal. Indeed, it is not uncommon for a student who has taken at least one-half of an undergraduate course in the humanities to assume that this unmasking is the height of scholarly inquiry rather than a crucial step in the pursuit of the real, or the good, or the beautiful. Scholars of far greater stature delight in tearing down idols and icons alike.

In light of this, when medieval historian Joel Kaye proposes that our idea of what balance means is a product of history rather than a universal and constant intuition, one can be forgiven for a certain skepticism. Nevertheless, such suspicion would be misplaced. In his magisterial A History of Balance, 1250-1375: The Emergence of a New Model of Equilibrium and its Impact on Thought, Joel Kaye offers the prolegomena to a larger history of balance that has not been written, but which is essential for understanding and responding to the medical, economic, and political crises of our day.

In his previous work, Economy and Nature in the Fourteenth Century, Kaye argued that the monetization of Europe and increased complexity and frequency of trade was a catalyst for the scientific developments of the fourteenth century. Here, he turns to models of balance as a key stage in the movement from experience to the formation of ideas: in his words, “models of equality and equalization serve as the primary medium through which social, economic, and technological environments affect and activate the production of new perceptions, new imaginations, new insights and ideas, and even radically new images of the world and its workings.”

This understanding of the role that models of balance play gives rise to a unique difficulty in tracing the history of balance: namely, that Kaye is tracing the history of something that looms behind language and theory: a sense, a feeling that sits behind words like equality, justice, order, and even health, and is not confined to a single term or concrete idea. Nevertheless, the ubiquity of balance in its attachment to and shaping of so many ideas lends the concept of balance its strength as an interpretive lens. If we can disentangle the web of notions that intersect with balance, we can gain greater insight into the transformation of conceptual worlds.

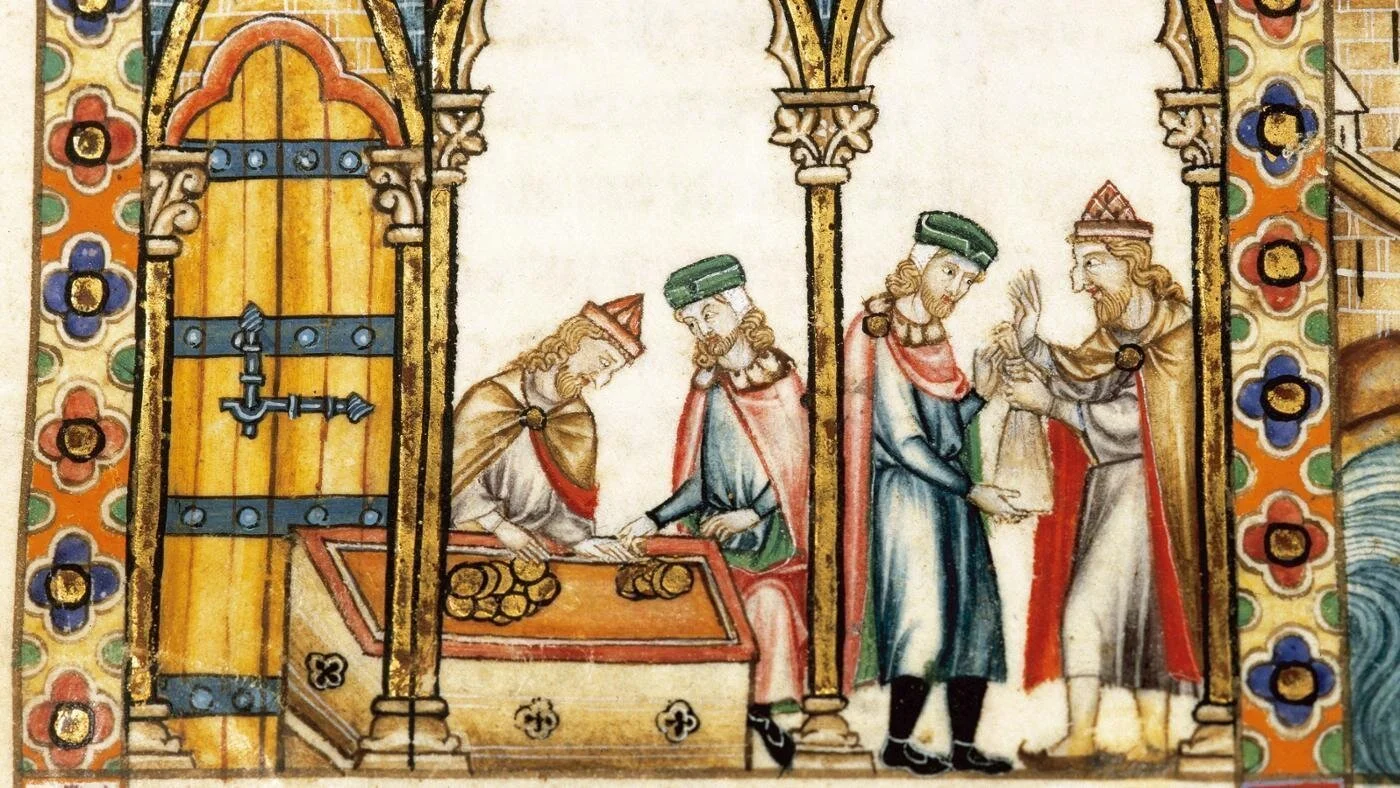

Kaye’s narrative begins with the “old model” of balance found in the thought of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. Though Kaye never provides a succinct definition, what the old model of balance boils down to is something that originates in the world or is imposed by a rational agent. The old model assumes a fairly static view of the world. It can be seen especially in their treatments of usury and just price. To avoid usury, a borrower must repay exactly what was lent: no more, no less. Just price requires that the two sides of the exchange have equal value. The focus is on the individuals rather than the system, and less attention is given to the dynamism of prices and the multiplicity of interacting causes that produce them.

The new model arises between 1280 and 1360 with such figures as the Franciscan theologian Peter Olivi, the physician Turisanus, the political philosopher Marsilius of Padua, and the Scholastic polymath Nicole Oresme. To summarize the new model in any brevity is to color in crayon, removing not only nuance and detail but also much of the beauty of Kaye’s insights about the nature, source, and import of order. At the core of the new model is the discovery of self-ordering and self-equalizing systems, which has a host of implications for how one understands the world and one’s actions within it. Chief among these, balance becomes a result of opposing forces rather than something built into the world or created by a rational actor. The central role of God and human agent is thus at least partially displaced by the activity of the system. Hierarchies fall to relationality, and the static world gives way to one in flux.

Kaye traces these features through diverse areas of thought—economics, medicine, politics, and natural philosophy—as he documents both the existence and effects of such a shift. In economics, it is seen in the trust of what we now call market forces to set prices and in the shift in focus from individual transactions to the benefits of the economic system when functioning as a whole. In medicine, we see it in the rediscovered concept of the Galenic body, in which health consists in a balance between opposing forces. And we see the political effects of that metaphor transferred to the self-ordering body politic in the work of Marsilius of Padua. The new model dies out, Kaye tells us, in part because of the perceived failures of society and economy to self-regulate in the face of the Black Death. While his earlier De Moneta epitomizes the new model of equilibrium, Nicole Oresme’s Le livres de politiques—a vernacular translation and commentary on Aristotle’s Politics—shows a return to the older model a mere fifteen years later.

Let historians dispute the accuracy of Kaye’s account. I am neither qualified to quibble nor inclined to be a quibbler. (No offense intended to those with different chops and tastes.) What intrigues me—and what should excite other readers of the Genealogies of Modernity blog—is the project that Kaye introduces: namely, a new inquiry into the history of balance that might complete the narrative that Kaye begins. Kaye’s study only takes us as far as the fourteenth century, and so we are left wondering how the history of balance continues. Tracing the decline of the “new model” of balance and the rise of a similar, still-newer model of equilibrium beginning in the sixteenth century could shed much light on the rise of modernity for historians and constructive thinkers alike. How might our understanding of Hobbes, Spinoza, Pascal, and Descartes change when we read their work as a part of the history of balance?

In the first place, the narrative could challenge our standard periodization. We may find that many of the features we consider distinctly modern are already present in the “new model” of the fourteenth century. For instance, the dynamism that sets apart the conceptual universes of Adam Smith, Darwin, and Einstein is in some sense already present in the works of the philosopher Nicole Oresme. Is there a medieval modern, or do we need to further refine our notions of modernity in order for them to carry analytical weight?

Second, and this will be of particular interest to scholars of religion, this narrative of balance is integrally linked to the history of religious ideas and debates about secularization. We need a more complete narrative in order to see whether the “new model” of balance is indeed a secularizing force—as Kaye argues—or whether it instead models an integration of religious belief with the belief in a world in flux. If the latter, it might provide resources for theologians operating in the wake of the modern prophet of contingency: Hegel.

More broadly, and arguably more critically, a genealogy of balance promises to help us understand what it is to be an agent in the modern world. Ideas have afterlives: they live on in subcultures that intentionally preserve them, in practices that have long lost their justification, and in our contradictions and nagging doubts. Consider our response to the latest crises. Imperatives to “flatten the curve” as COVID-19 has spread across the world were issued in the dialect of the new equilibrium, but they implied a conception of moral responsibility that is decidedly pre-modern. Where I live, few people suffer from COVID-19, which means that whether one individual wears or does not wear a mask is statistically insignificant. These things matter immensely in the aggregate, and yet, to hear some speak, the maskless individual is as good as a granny-killer. A response in keeping with the newer models would have been systemic, focused on incentives and structures rather than the transformative power and solemn responsibility of the individual agent to restore order. The backlash against those engaged in “price-gouging” of N95 masks and hand sanitizer was fast and thorough. Nevertheless, our economic models of equilibrium have no way of making sense of retail arbitrage as harmful. Instead, our moral judgments echo the conceptions of just price promoted by Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas.

The ethicist in me would like to push one step further, to move beyond the hermeneutics of culture in pursuit of normative implications. As a hermeneutical realist, I take it that the real is communicated to us through cultural signs and symbols. It is possible that our constant return to the old model of equilibrium represents some aspect of the real that was encapsulated within it yet which is not revealed in our modern conception. Perhaps our agency is not fully accounted for in a world dominated by self-ordering or self-equalizing systems. More fundamentally, maybe order is not solely the (temporary) result of becoming; perhaps being wishes to make an appearance. If—and here it must remain an if—this were the case, then the genealogy of balance might uncover philosophical resources crucial for understanding not only our modern conception of action, but action itself. May the historians take up Kaye’s project, so that the rest of us can glean their insights.

John Buchmann is executive director of Beatrice Institute and a moral theologian contemplating mammon. He received his PhD in religious ethics from the University of Chicago.