The Possibility of True Art: On Modern Art

Composition by Mark Rothko

Agnes Martin’s oft-cited praise of Mark Rothko’s paintings, that they “reached zero so that nothing could stand in the way of truth,” captures the sense that modernist painting, especially as it was instantiated in postwar New York, was truly a new beginning. We can read this as a declaration that Rothko is a “zero,” a nothing, a demolition of everything that came before and a fresh ground upon which a new future of painting could be built. It’s almost as if art starts over with modernist abstraction. Indeed, it’s a common narrative that modernist art breaks away from the past, and that while it comes at the end of the western tradition, it does so as a negation and not a continuation of it—that however much it depends upon the western tradition, modernism is the final and ultimate rejection of the values that made western art what it was.

But I wonder if this is the right way to characterize its relationship to the western art tradition. Indeed, I wonder if there’s another way of understanding what’s at issue in the western tradition—not a narrative but an ethos; not a straightforward story of development but an idea that resurges again and again in the history of western art and reaches a kind of fever pitch in the modernist project. Considering the western tradition from this point of view, I wonder if it makes more sense to say that modernism did not break western art but instead attempted to fix one of its most enduring problems.

I think there are crucial questions that have been operative in the western tradition since its earliest roots, questions that have gotten lost in our busy dismissals of the deeply problematic Hegelian interpretation of the western tradition as a grand narrative of collective spiritual progress, questions that make sense of some of the more striking features of modern art. This will, naturally, ground a different approach to the western tradition and to modernism as its capstone—not as a specious narrative, but as a persistent ethos that is as vital today as it was for the modernists.

* * *

Three features common to much modernist work circa the first half of the twentieth century are worth attending to in this respect: (1) an emphasis on abstraction or an increasing self-consciousness in the use of the elements of the art form, (2) an almost hostile relation to the audience, an often intentional cultivation of an unpleasant appearance, almost an embrace of the ugly or jarring, and (3) an expectation that the audience work for a genuine encounter with the artwork—that the painting not give itself away—a certain dependence on the viewer’s education and willingness to exert a pretty high degree of effort and attention to be able to receive the work in a genuine way.

These can be big stumbling blocks for people struggling to make sense of modernism and are often grounds for rejecting modernist art from both a progressive position (as failing in an essential way to speak to an audience without an elite education) and a traditional one (as having abandoned the great western tradition of truth, goodness and beauty). That is, they’re often cited as the points where modernist art departs from the western tradition. I think that the opposite is actually the case and that these characteristics of modernism are the points where it is most deeply connected to its western roots, the points where it most fully embodies an ethos that has been (at least) latent across a broad swath of the western tradition and present in other traditions as well.

I think that the spiritual task of the modernist artists was to take a very old and abstract set of principles/worries/questions that have been built into the DNA of western art, and not only make work that was guided by these principles away from major pitfalls and dangers endemic to art-making, but also to shake off all of the accretions of western art and start over, start anew, with only the ethos to go by. This imperative to start afresh was particularly urgent for the visual artist attempting to address the deepest human content at issue in the great artistic tradition in the west, for an audience living in a more radically new visual environment than any generation before them.

It was a tall order. But if we can see the continuity of their project with deep currents of thinking about art in the west, it opens up the possibility of taking hold of a tradition that reaches into the ancient past and that is still available in this contemporary, or post-contemporary moment—so that modernism is neither a break nor a rupture, not an endpoint, not a hermetic and historically remote occurrence, but an occasion where fellow travelers undertook a particularly arduous task and laid critical groundwork for an uncompromising future.

* * *

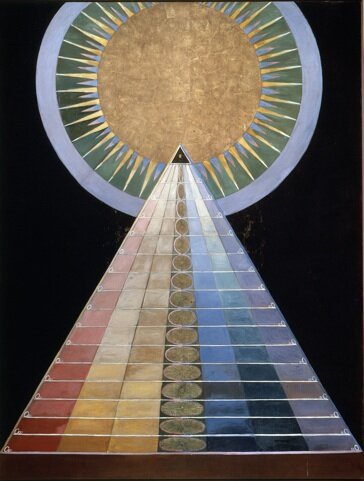

Altarpiece by Hilma af Klint

Far from being a minor, technical, or formal task of arranging shapes and colors, or even the branding achievement of a “signature style,” the motivation toward abstract painting was an outgrowth of an ethos central to the western tradition, felt by the modernist artist as an urgent and pressing issue. From painters like Hilma af Klint, who understood that her pure abstractions would be incomprehensible to her contemporaries, to early advocates of pure abstraction like Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Sonia Delaunay, and Wassily Kandinsky, to those committed to figuration like Matisse and Picasso, and on to the New York School painters, most of whom abandoned figuration for full-fledged abstraction in their mature work, the question of abstraction—of whether or not painting should include recognizable figures—was very pressing. Hotly debated, embraced by some and rejected by others, alternately an article of faith and a byword for obfuscation, the movement to a more abstract art was a fundamental issue in mainstream modernism, especially in the first half of the twentieth century.

Even within the art world, the word “abstraction” has been an uncomfortable fit with the set of characteristics grouped under the label, though the word has hung on as a useful label. Often opposed to “realistic” painting, “abstract painting” tends not to look like a photograph. Sometimes there’s a recognizable image, even if it’s not “realistic,” but abstract paintings can also be pure shapes, or fields of color, or even splatters of paint. When I was teaching a lesson about abstraction to a class of second graders, I showed them some examples of “abstract” and “realistic” paintings on the projector, and then I asked the class what it meant for art to be “abstract.” A girl in the back row raised her hand and gave a great answer: “A painting is ‘abstract’ when you can tell that it’s a painting.”

It’s a great definition, and it picks out almost the same developmental arc of modernism that the influential critic Clement Greenberg claimed for modern painting. Greenberg argued that painting was moving forward, was developing and not regressing, insofar as the means of making the painting became more apparent. It was a development from a point in which the means of making a painting were obscured (as in nineteenth-century academic paintings that look like photographs) to one in which the painterly means are all highly visible and the painting does not aspire to be anything but a painting. It is a development, that is, toward paintings that look more and more like paintings.

Still Life with Grapes and a Bird Antonio Leonelli (Antonio da Crevalcore)

* * *

So what does this have to do with the western tradition? Isn’t painting in the West supposed to be about representation, from Apelles’ grapes that fooled the birds to the development of linear perspective in the Renaissance? To draw out the connection, I’d like to turn to a passage in Plato’s Republic that artists love to hate, the place where he rejects the work of painting as downright immoral:

Consider, then, this very point. To which is painting directed in every case, to the imitation of reality as it is or of appearance as it appears? Is it an imitation of a phantasm or of the truth?

Of a phantasm, [Glaucon] said.

Then the mimetic art is far removed from the truth, and this, it seems, is the reason why it can produce everything, because it touches or lays hold of only a small part of the object and that a phantom, as, for example, a painter, we say, will paint us a cobbler, a carpenter, and other craftsmen, though he himself has no expertness in any of these arts, but nevertheless if he were a good painter, by exhibiting at a distance his picture of a carpenter he would deceive children and foolish men, and make them believe it to be a real carpenter (Republic 598b-c).

I’d like to pay closer attention here to the reasoning than to the conclusion, because it reveals the questions and worries that Plato had about art. He knew that art could be powerful, and he also knew that its power could be applied to good or bad ends, that it could foster nobility as well as it could enable foolishness. So he worried about it—and his specific worry is really telling.

He worries that painting can fool people, make them believe that something is there that isn’t really there. He worries about a painting that looks so much like a window that someone mistakes it for a window, so that the painting leads the person to error, to falsehood, to foolishness. He worries about painting that aspires to this, to a skill so refined that it bewilders even the birds, like in the story of Apelles. Plato’s concern is especially interesting in light of that second grader’s definition of abstraction, of that defining feature of modernist painting: that an abstract painting is a painting that looks like a painting.

Escaping Criticism by Pere Borrell del Caso

There’s a striking inference here: if Plato’s biggest worry about painting is that it can appear to be something else, then the greater the degree of abstraction, and the concomitant greater degree to which the painting can’t be mistaken for something else, the more trustworthy the work—the closer it can potentially come to truth. This critical idea gives weight to the urgency of the question of abstraction for modernists, because it elevates the art of painting to something that can go deeper than the reproduction of appearances. It situates the trials and frustrations of modernist painting as a response to an imperative buried in the heart of the western tradition—that painting not be imitation, but in some critical way, be itself. This was the imperative painters struggled to fulfill, every bit as difficult as the Socratic imperative to know thyself; and it was this imperative they had to fulfill in order for painting to be able to seek after truth, the deep truths I believe those painters saw latent in the painting of the past, and which they desired to make visible in a visual language beyond the kind of reproach implied in Plato’s criticism, for a future in which painting could be something more than decoration.

In the two coming installments, I’ll talk about the second and third qualities of modernist painting: (2) hostility to the audience and (3) expectation of effort on the audience’s part to receive the work.

Tom Break is an artist, critic, and editor at In the Wind Projects.