On Meaning and History

1.

Modern thought might be characterized by the distinction of nature, action, and knowledge. Sometime in the seventeenth century, it became possible to think of method, rather than experience or authority, as the proper ground for knowledge. Knowledge fares well considered like this, for its justification is susceptible to a continuous refinement. The progress of knowledge is an image of a justice divorced from both subject and object, act and nature. Yet it was to this image that history was assimilated. The progress of history was modeled upon knowledge. Nature, until recently, remained below this progress, confined to its own rhythms and cycles. The romantic imagination of the temporality of nature was a refuge from the ostinato of knowledge on the march.

Schiller’s paragone between naive and sentimental poetry captures the most distilled expression of mature ahistorical thought that characterizes romanticism. Love is purest when the grounds for this feeling come from the mere fact that these things are natural. The bourgeois gentilhomme disguises his amour propre with this romantic love for nature. He ascribes an unearned immediacy of value to all that is natural and distances this from the “artificial” valuation of products of labor. A world constituted by labor horrifies Schiller’s romantic gentilhomme. The artificial rose, no matter how perfect a facsimile, will never bring the joy of a natural rose, for that would mean that “[i]t is not these objects, it is an idea represented through them, which we love in them.” Yet the mediation of love through an idea is perhaps the most widely expressed sentiment in the poetic tradition he reflects upon. Dante made from the sight of Beatrice a “schermo de la veritade,” a screen of the truth, and Cavalcanti’s love takes its place “dove sta memoria,” that is, in memory. Narcissus falls in love with himself, but only by misrecognizing his reflection.

2.

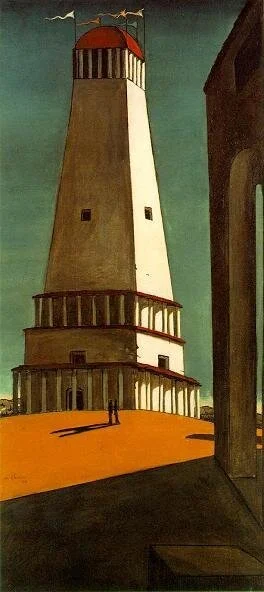

Piazza d’Italia, Giorgio de Chirico, 1913

Contemplation does not refer to life. Its thought turns around the significance of what is dead, ruined, and removed from use. Yet it is wrong to think that the contemplative is unconcerned with life. This is her whole concern. To look directly at life, as the romantic attempts to do, is to be called into it, and so one’s gaze becomes the beautiful soul’s refusal to act or transforms into a confused single-mindedness of the rash. The purposes of the living cloud the meaning of their acts and their omissions. Intention is only in the attempt, not the deed. The meaning of an act is discovered in the dialectic between the stretched hand and what it finds. Though the meaning of an act may look to the intention of the actor, it is an error to think that one can intend the meaning of an act. Intention precedes action; meaning follows. It is the unbridgeable chasm between these two that engages action and contemplation in a never-ending dialectic. Not only do action and contemplation exclude each other in activity, but they are, for that same reason, each constituted by the lack of the other. No intention can be the cause of meaning, and meaning cannot be the cause of action.

Contemplation practices this finding precisely because action cannot. The actor suffers, in the ancient sense of pathos, the meaning of her own action. Like an ancient augur, the contemplative delineates a place for meaning and treats it as an image, allowing whatever moves through it to be read as an intention. This divinatory practice is only false when the accidental and contingent character of this motion is forgotten. Varro’s etymology of templum reminds us of this. Where the term first meant whatever was gazed upon, it was taken up in the formulae of rituals to mean the area marked on the ground by the augur’s wand. It is the augur’s lituus or wand that comes forth in intention, but it is the flight of birds that gives this act its meaning.

3.

The fact is found in the carcass of knowledge. Its own time has passed when it is discovered, a truth preserved in the etymology of its name: factus, what has been done. Only after the process of decomposition is complete does the skeletal form of pure knowledge appear. Here is where the fact appears to have achieved its end, fitted into the larger structure of the skeleton. Once moved from the site of its mortal fate, science can only preserve these skeletons, through some fiction that returns the long-rotted flesh of fact’s carcass to the fossils science has collected. This dream of life is what is called theory, the ability to see life in what is dead. But in assembling the elements of theoretical knowledge, even the boldest scientist will always be more timid than the parasite who depends upon finding fresh carrion. For the vultures must know something of the alien life of what gives them sustenance. Their widest circuit is traced around the animal in danger. The vulture may have many names. One of them is historical materialism.

4.

Camus’s and Sartre’s existentialism sought to make the meaning of an act dependent upon the individual will, just as the theology of occasionalism, whether al-Ghazali’s or Malebranche’s, had made causality the sole province of God’s will. The French existentialists were shocked by their realization that the cause of one’s existence could not justify it. Yet their solution, the trivial freedom of an arbitrary will, dissolved their cherished vision of a meaningful existence. Life consists of both action and contemplation, neither of which is achieved or maintained through freedom. Dreaming is the originary form of contemplation, and all contemplative practice seeks to reproduce the realm of the dream in a waking state. The dream does not cease to be meaningful because we forget it. Indeed, Freud postulated that the forgetting of dreams was a defense against the discovery of their meaning. Materialism is only historical when it restores action to irony, showing the meaning of an act to exist outside of the act. To see one’s own life as historical, in this sense, does not mean giving it some grand significance by its participation in important events, but refusing to assume that the meaning of a life can be discovered within life itself. No meaning, even the meaning of one’s own dreams, can ever be the private possession of the willing subject.

5.

Nostalgia of the Infinite, Giorgio de Chirico, 1911

The historian is a contemplative. Her intention can never be the meaning of the facts she seeks to rescue from pure knowledge. This is the attitude of the historicist who assumes that the value of historical work comes from its status as knowledge. For the historicist, the meaning of the past is confined within its own time. The correction to this is not to abrade the details of history so that they become motives for living action. Rather, the motive of present actions is clarified by history, for there we see our motives are not our own. Our common speech shows how the present looks to history not as a story of the past, but for its own significance. We hear it said, often in the most profane way, that “history will look back on this moment and say . . .” The speech of history is the intimation of the meaning of our lives that now escapes us. We live towards our own history. Beauty is the promise of happiness, as Stendhal said, so history is the promise of meaning.