Uncomfortable Truths about Our Times: Beef & Notes from the Underground, Part II

Part I of this essay is available here.

One question raised by Notes and Beef is whether or not this extreme anger is sick or actually the most appropriate response to a sick world. Are these characters missing out on real life? Or are they more alive because they see the world for what it is and allow themselves to experience their darker emotions? In episode 10, Danny and Amy reflect on how different they are from the people around them. “You think other people feel this way?” They both know George does not. “I don’t know. Maybe we’re not normal. Maybe we’re too f--- up.” “Or, maybe normal people are just delusional f---ed up people.” Certainly those around them do not understand them. In episode eight, Amy’s husband, George, says, “I don’t understand how you could hate this guy so much.” She does not understand it herself.

The Underground Man develops both a sense of inferiority and one of superiority from the contrast between himself and others. “I did not believe that others experienced such feelings, and so I kept them to myself, secretly, my whole life. I was ashamed (and even now, perhaps, I am still ashamed)…I would gnaw at myself, chew myself up inside for it, nag and badger myself until that bitterness finally turned into some kind of shameful, accursed sweetness, and finally—into a distinct, intense pleasure!”[1] Like Amy and Danny, the Underground Man is allowing his most basic self to see the light of day. It makes him feel more alive. It also makes him feel profoundly alone.

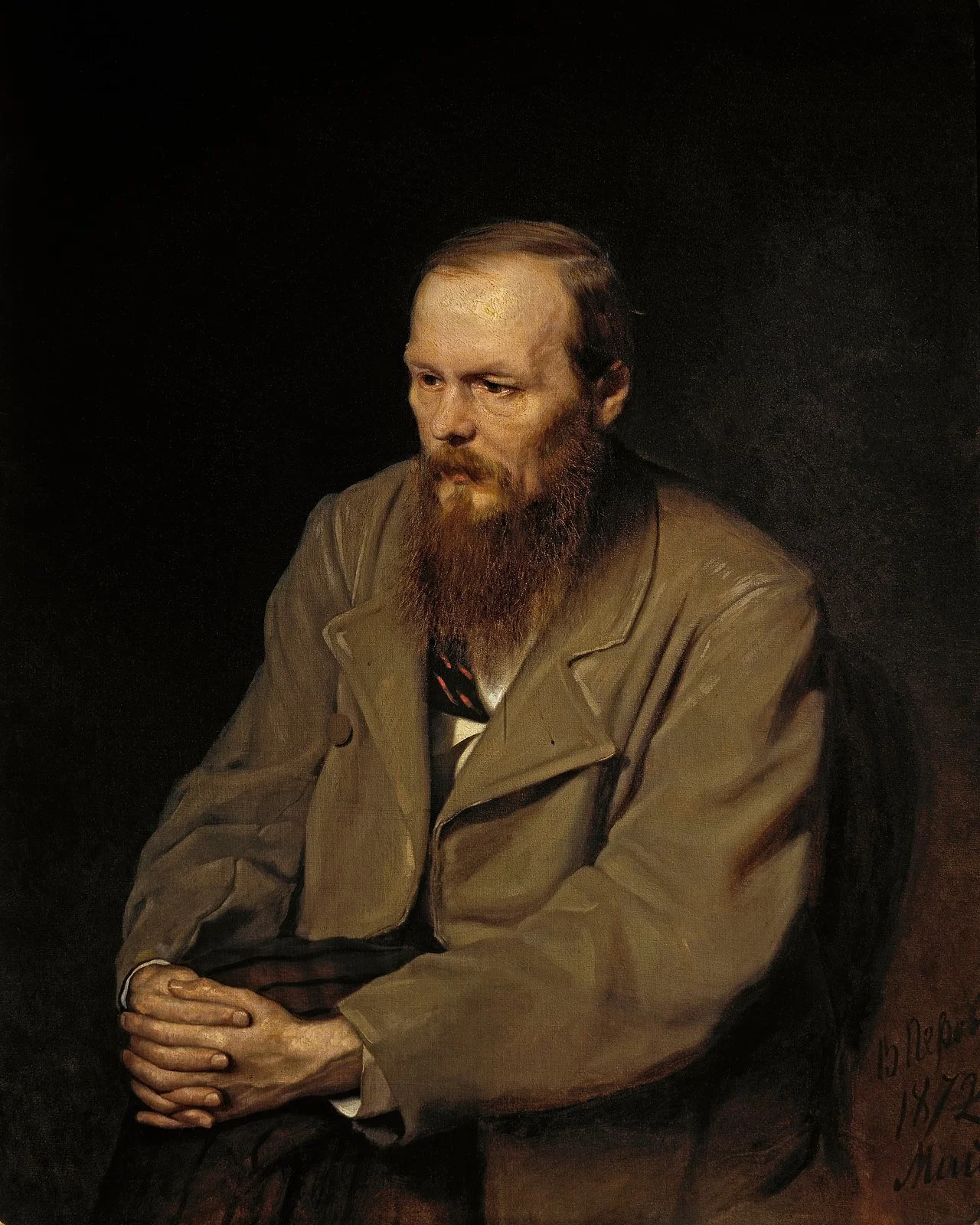

Fyodor Dostoevsky by Vasily Perov, c. 1872

Venting their hate on each other helps Danny and Amy confront their circumstances, but it does not bring any real relief. Their hate is also internally directed. Amy wonders if she is harming her family just by being around them. In episode 10, Danny reveals what he believes about himself in a moment of exasperation when he yells, “F---! I mess everything up.” The Underground Man hates his old school friends and strangers on the street, but he also tells us: “I would quite often look at myself with furious dissatisfaction, culminating in loathing, and in my mind I would attribute my own feelings to everyone.”

Beef and Notes From the Underground raise real questions about determinism alongside the trying circumstances of their times. Danny and Amy struggle to identify who or what is responsible for how messed up they feel and are. In episode 10, Danny muses that parents, “just, like, piss their trauma down.” Danny and Amy also consider the possibility of a god in the face of their emptiness. “If there is a God, why is it like this?” But then, what if everything is God, which means we’re God, too? Then we can say that life is like this because we’re like this. Maybe “God is just trying not to feel alone in nothingness.”

In contrast, the Underground Man tell us that he enjoys making bad choices, because it demonstrates his ability to choose. The world around him believes in determinism and suggests that a man will be rational and make the right choice when he is given the option. Well, he won’t. He lives off this spite, even though it hurts. He may have some doubts about his control over his nature, but living in spite is at least something he can control and choose for himself. It is his only way of asserting himself in the world.

In a world like this, is real connection with others possible? The Underground Man has no real friends and rarely goes out. He has an opportunity to connect with Liza, a prostitute, who he has suggested he will help. When she arrives at his apartment, she is open to him and ready to love him. He is embarrassed by his home, then by his resulting tears. “I stood before her crushed, disgraced, repulsively embarrassed.” She is sympathetic, but his pride punishes them both. He tells us that “something hideous instantly crushed all the pity in me; it even egged me on further.” Having felt humiliated, he wants to humiliate her. He does. And she soon understands that he is “a nasty man, and, most importantly, incapable of loving her,” because he only wants to “tyrannize and assert moral superiority over another.” She leaves and he loses his chance at a genuine human connection. He decides, “They don’t let me…I can’t be…good!”

William Blake, Agony in the Garden, 1799–1800

Beef holds out some hope for connection. [Spoilers ahead] Amy and Danny both hide things from those closest to them and often lie to them. Amy confesses, “I don’t want anyone to see who I really am.” She believes that if they see who she really is, they will not be able to love her. But in the final episode, we see Danny and Amy finally have some kind conversations with each other. Amy comforts Danny about his past, saying, “I’ve done some shameful things, too.” As the episode gets stranger, they learn more about each other’s lives and look on one another with compassion. One tells the other: “I see your life. You poor thing. All you wanted was to not be alone.” In response, is a similar reassurance, “You don’t have to be ashamed. It’s okay. I see it all. You don’t have to hide. It’s okay.” Connection seems possible. Sympathy can move the plot forward.

Beef and Notes From the Underground are wrestling with big questions about human existence—questions many use faith to identify and answer. Beef tells us as much. There is a moving scene in episode three when Danny goes to church and the congregation is singing “O Come to the Altar.” As the lyrics progress, Danny begins to cry, and then to openly weep.

Are you hurting and broken within?/ Overwhelmed by the weight of your sin?/ Jesus is calling/ Have you come to the end of yourself?/ Do you thirst for a drink from the well?/ Jesus is calling/ O come to the altar/ The Father’s arms are open wide/ Forgiveness was bought with/ The precious blood of Jesus Christ

Though Beef does not end with a “born again” moment, it points us to the hunger for one. Danny and Amy are flawed and incapable of overcoming their flaws on their own. They want desperately to be better and be loved, but they are filled with despair. Danny’s involvement in church eventually turns out to be less of a fresh start than it seems it could be, but the hope of faith is represented even if it is not exactly found by Danny.

Neither Notes From the Underground nor Beef attempt to offer us a complete solution for the human condition or our circumstances, but they prompt us to ask important questions. The Underground Man concludes: “I missed out on my life as a result of moral corruption in my corner, the inadequacy of my surroundings, my detachment from the living, and my vain spite in the underground…”[7] We can watch these stories from our corner, but if we take them seriously, they can help us confront our own moral corruption and consider whether or not something better and more beautiful is possible in our circumstances.

Elizabeth Stice is a professor of history at Palm Beach Atlantic University. She has a book about World War I, Empire Between the Lines: Imperial Culture in British and French Trench Newspapers of the Great War, and she has written for various publications, including Front Porch Republic, Comment, and Inside Higher Ed. She is editor-in-chief of Orange Blossom Ordinary.