Three Critiques of Secularism

Is it possible to critique secularism in a thoroughly secular age? Is it possible to invoke the divine while dwelling within the “immanent frame”—i.e., the modern view that everything in our world can be understood without reference to any external, transcendent order? I want to suggest, in this essay, that we can critique secularism in a secular age, but only by identifying the metaphysical boundaries of the secular age—those boundaries that demarcate the real from the unreal, and the legitimate from the illegitimate.

The three critiques I offer below attempt just that. They are made not on secularism’s own terms, but from beyond the secular order. This is, I must note, not a novel exercise. In recent years, scholars have offered penetrating critiques of secularism, from the epistemological (Talal Asad) to the metaphysical (John Milbank). In line with this scholarship, I want to level three critiques of the secular from a Qur’anic metaphysical perspective. Together, these three critiques pivot around one key critique: secularism is a philosophy of alienation.

1. Secularism and Fetishization

Secularism is the philosophy and legitimation of fetishization. Fetishization is the process wherein that which is man-made is made to appear as though it is absolute, divine, and eternal. In the Qur’anic story of the men of two gardens, the richer of the two arrogantly exalts wealth above everything else, including God: “Then he entered his vine-yard and said, wronging himself: ‘Surely, I do not believe that all this will ever perish’” (Qur’an 18:35). By the end of the story, God sends a storm to destroy the garden as a rebuke to the rich man for fetishizing his worldly possessions.

However, fetishization finds its essential act not in exclusively divinization or absolutization but in what precedes it: the act and appearance of closure. To appear closed means that an order (e.g., a politico-economic system) legitimates itself through itself in a circular fashion. In other words, it does not present itself as contingent and historical but divine and absolute, as though created ex nihilo. The Qu’ran refers to this as istighna, or self-sufficiency. As in the case of the rich man of the two gardens, the Qur’an states: “Nay, surely man transgresses; for he believes himself to be self-sufficient” (Qur’an 96:6-7).

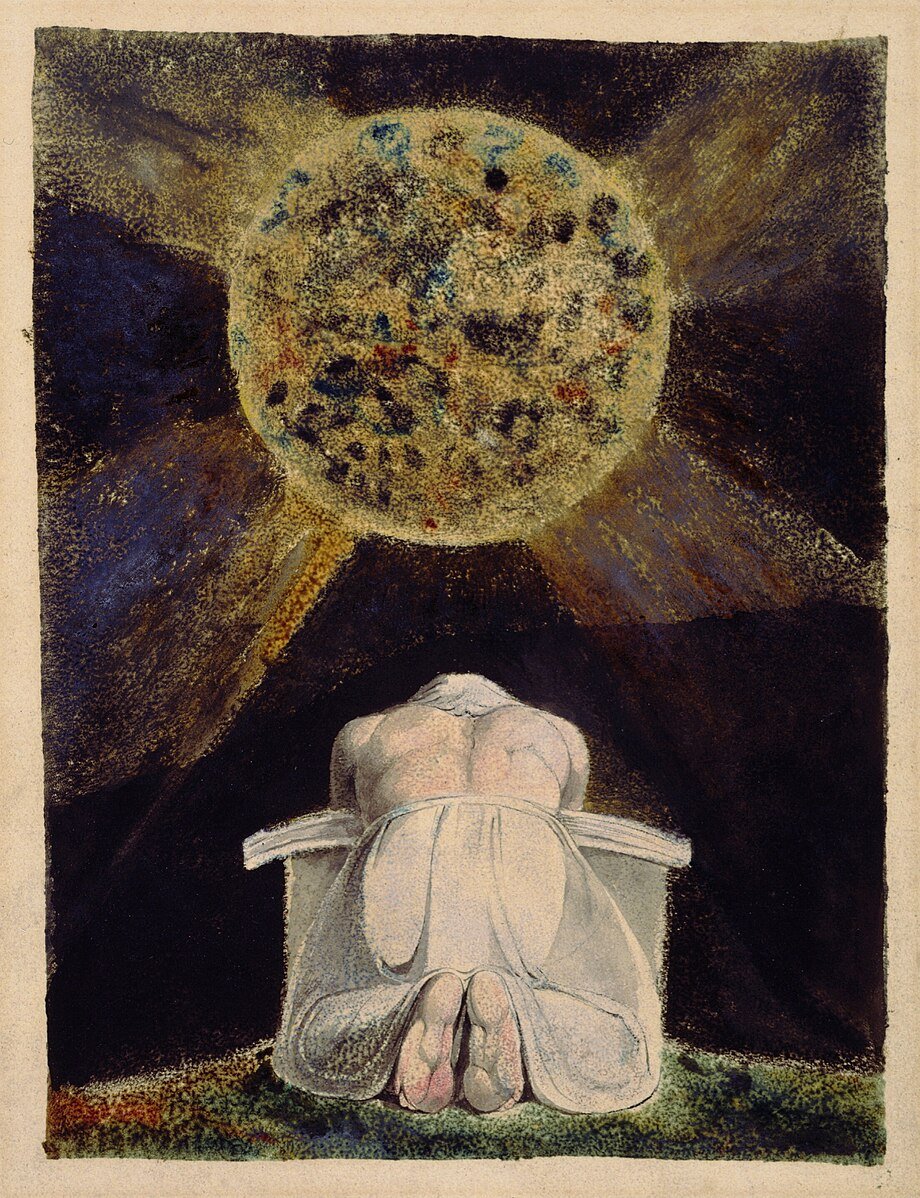

William Blake, Frontispiece to The Song of Los

This act of closure is the hallmark of any oppressive order because the oppressive order must negate any possible source of exteriority—i.e., that which emanates from beyond the order itself such as God who is uniquely transcendent—because exteriority always threatens to breach the confines of the self-enclosing order. Enrique Dussel writes in Philosophy of Liberation:

Totality, the system, tends to totalize itself, to center on itself, and to attempt—temporally—to eternalize its present structure. Spatially, it attempts to include within itself all possible exteriority.

The world, perceived as self-sufficient, is stripped of any relationship to the divine which in turn alienates the world from any reference to the sublime. In negating the divine–worldly hierarchy, the temporal forms of this world (e.g., nationality, race, economic class) become absolute hierarchies, rather than contingent properties, because the only point of reference in the “immanent frame” is the worldly. The world, in short, becomes a pantheon of idols.

2. Secularism and Transcendence

This second critique follows from the first. Secularism is the misplacement of transcendence. It replaces the transcendence of a higher order with that of a lower order: the immanent. Eric Voegelin explains how the transcendent grounds (the ultimate foundations of reality) have been immanentized. Because God is removed from the equation, the transcendent must be placed elsewhere. The immanent, writes Dr. Haggag Ali in Mapping the Secular Mind: Modernity’s Quest for a Godless Utopia, means: “‘indwelling,’ ‘inherent,’ ‘operating from within.’ Therefore, anything that is said to be self-contained, self-operating, self-activating, or self-explanatory could be described as ‘immanent,’ since its laws are inherent to it and its operating force is internal.”

This sacralization of immanence negates what is intrinsically distinct in man, for man is a being who wishes to participate in some form of transcendence. For example, in the Chinese tradition, there is the Tao. In the Vednatic tradition, there is Brahman. In the biblical tradition, there is Yahweh. The ontological concern of man, in his primordial state, is to ask: who am I? What is my relationship to the cosmos?

3. Secularism and Oppression

The root of “oppression,” as Marilyn Fyre points out in The Politics of Reality: Essays in Feminist Theory, is the word “press:” “Something pressed is something caught between or among forces and barriers which are so related to each other that jointly they restrain, restrict, or prevent the thing’s motion.” As such, oppression is a form of power because it can restrict and delimit spaces of thought and action. In other words, power manages the threshold of what we deem to be possible and impossible. The immanent world, stripped of its relationship to the divine, becomes the only space of thought and action, and the self can no longer strive toward the sublime. The world is reduced to a space of pure power wherein the only form of action is horizontal action (immanent) rather than vertical (drive toward transcendence). If the drive toward the sublime—toward Truth—is an innate desire within man, then man becomes alienated.

Creation of the world in the Nuremberg Chronicle

The secular state achieves this alienation by recreating man, God, and the cosmos in its own image. The image of God is domesticated to fit the arbitrary designs of the secular state (e.g., reducing God to a deistic conception of God as a watchmaker). Through these acts of re-creation, the secular strips man of what makes him existentially unique, i.e., his desire for transcendence and drive to the sublime (what Paul Tillich calls spiritual self-affirmation). Taha ‘Abd al-Rahman, a Muslim Moroccan scholar, explains that man, in his primordial nature, is a vertical being (al-tawājud) that exists in two worlds: the seen and the unseen. In his deformed state, man is a horizontal being (inwijād) dwelling only in the mundane and immanent world. These “unique possibilities” of man are illustrated eloquently by Ali Shariati, who explains that through the Qur’an man has a dual nature, for he is created from both clay and spirit. The former is sedentary, drawn to the worldly and mundane, whereas the latter ascends toward the sublime. In other words, the secular (horizontal) self cannot participate in a higher order and is left only with the ability to participate in an immanent lower order.

Contrary to its self-declared narrative of liberation and progress, the secular age is an age of alienation—that is, both the alienation of the world from a meaningful cosmos that was once imbued with the grandeur of the divine as well as the alienation of the self from itself. In the secular age, the self is stripped of its primordial drive toward the sublime—a desire to participate in a higher, transcendent order.

Ali S. Harfouch is a writer and researcher on Islamic liberation theology, contemporary Islamic thought, and secularity. He is the author of Against the World: Towards an Islamic Liberation Philosophy (Ekpyrosis Press). He obtained his Master of Arts in Political Science from the American University of Beirut.