The Interaction Problem

Science is, so to speak, a jealous god: it wants to eliminate all rival accounts of reality. But in the twentieth century, several great philosophers and physicists came to the radical conclusion that there are strict limits to its ambitions: science cannot wholly do away with our ordinary impressions of reality without undermining the foundations on which the whole scientific project is built.

This, however, raises as many questions as it answers. Even if we accept that both science and ordinary experience must be given a place at the table, we’re still faced with the fundamental question: by what mechanism do they interact?

I want to propose a radical answer: that we will probably never know. After all, the question itself, at least as I put it here, still presupposes—and thus forces us back into trying to construct—a completely systematic picture of reality. But it seems increasingly likely that no fully comprehensive account is possible.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vituvian Man, c. 1490.

The scientific dream we inherited from the seventeenth century was that mankind should eventually be able to capture—in one all-embracing, continuous, and interconnected system—all human knowledge. It’s worth quoting Descartes at some length:

Those long chains, composed of very simple and easy reasonings, which geometers customarily use to arrive at their most difficult demonstrations, had given me occasion to suppose that all the things which come within the scope of human knowledge are interconnected in the same way. And I thought that provided that we refrain from accepting as true anything which is not, and always keep to the order required for deducing one thing from another, there can be nothing too remote to be reached in the end or too well hidden to be discovered.

Everything then should be deducible, as in math, by small, consecutive steps, leading from one corner of the vast grid of all human knowledge to the others. It should be like trying to map the entirety of the globe: as long as you know where you start, and you take care tracking your exact movements, you ought, in principle at least, to be able eventually to sketch out the whole thing.

But as the philosopher Thomas Nagel has recently argued, there’s one crucial step we don’t know how to make, and cannot foresee ever knowing how to make: that between the objective and subjective domains of reality. Imagine you could somehow attach a GPS sensor to every single atom in the universe and feed the data into an almighty computer. The map you reproduced would still lack a whole swathe of reality: the many billions of first-person perspectives that each of us individually inhabits—and which nobody, except the singular subjects occupying them, can “get inside.” Any final, objective description of reality must, if it is to qualify as fully complete, account for what it is like to be, say, a dolphin. And yet this task remains impossible from the outside. Our knowledge of reality thus remains necessarily incomplete.

This should be no surprise. When Galileo methodologically set aside all qualitative features of reality—colors, smells, emotions, ethics—it isn’t as though these things just disappeared. When Descartes bundled them all up and packaged them in a free-floating soul, he didn’t solve the issue either. The all-too-neat Cartesian distinction between mind and body is often ridiculed, but it was at least a flawed attempt to address a perennial problem: that there is something fundamentally different about the aspects of reality we encounter in first-person experience.

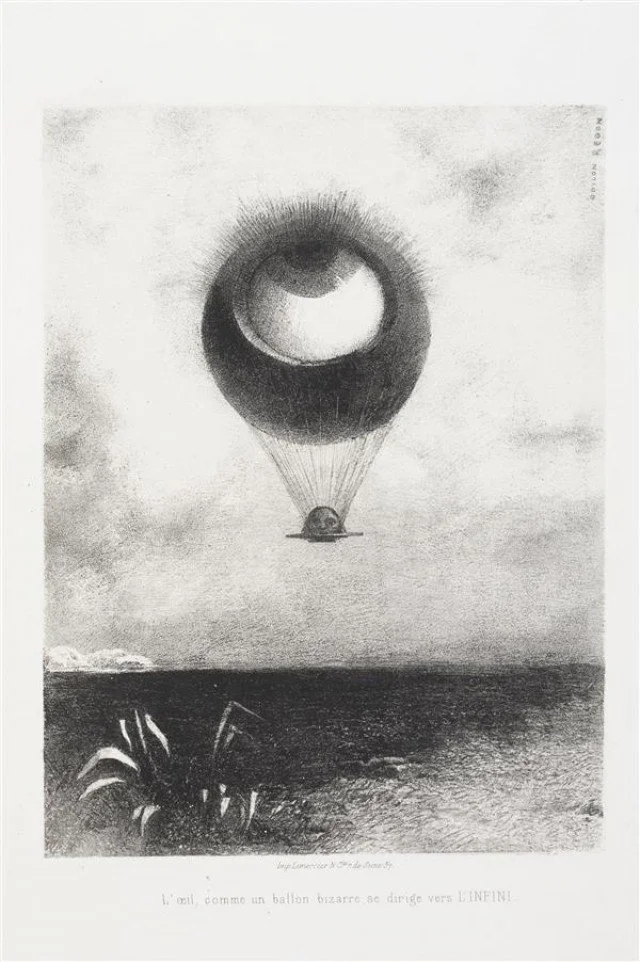

Odilon Redon, The Eye, Like a Strange Balloon, Mounts Towards Infinity, 1882.

We might, then, recast Husserl’s distinction between the world of science and the Lebenswelt as a distinction between objective and subjective reality—or rather, to see the Lebenswelt as objective reality plus subjective reality. The comparison isn’t perfect, but it at least helps to see why looking for some neat “interaction” between these two elements of reality is probably misguided.

To my mind, it remains an open question whether this boundary—between “subject” and “object,” “observer” and “observed,” “thinker” and “thing being thought of”—is a fundamental split between two different kinds of reality or the consequence of a conceptual error. Thomas Nagel obviously leans in the direction of the former explanation: the sheer implausibility of “knowing what it is like” to inhabit a different perspective suggests that perspectives are something fundamentally different from objective reality. On the other hand, somebody like Schrödinger, who had a quasi-mystical belief in the unity of mind and matter, leaned the other way. Our mistake, for him, is to think we have “extracted” an objective structure from the world when the two “halves” are really one and the same thing. We make a further mistake in thinking we can slot the two back together using only the terminology of the artificially simplified schema.

I oscillate between both positions. But I am drawn to Nagel’s humility—to his gut feeling that understanding the link between the two domains goes beyond our limited minds, as impossible as imagining what came before the Big Bang. We might be able to spot relationships and correlations, but a complete explanation eludes us. If we accept this, our whole approach to knowledge changes: no longer do we think we can start from one claim (“science is the ultimate arbiter of reality”) and derive all others from it (hence dispensing with any claims that cannot be reconciled with the first). Instead, we begin “from within” experience, take it all in as a whole, and try to identify the most plausible features as we find them in front of us. Both science and ordinary experience seem overwhelmingly plausible, so why not try to build a fuller picture around both?

Hidden Sources and Circular Reasoning

In any case, the “subjective” side of things frustrates the goals of science in still another way: it evades full analysis. Descartes’s method was to break everything down into its clearest, most elemental parts, and then build up a full map of reality: “we first reduce complicated and obscure propositions to simple ones, and then, starting with the intuition of the simplest ones of all, try to ascend through the same steps to knowledge of all the rest.”

But when we actually attempt to go inside ourselves and figure out what, say, understanding is, it turns out to be impossible. Wittgenstein, for instance, pointed out that you can never isolate a single, discrete “reason” for believing anything: a clear-cut reason must necessarily be expressed in linguistic form—in a sentence—but one’s understanding of that sentence depends on one’s understanding of language as a whole. Any justification one gives for a belief, then, is really a huge mass of tangled justifications.

Similarly, Heidegger pointed out that much of human knowledge is not a literal, conscious, step-by-step calculation of discrete propositions, but arises from our being physical creatures, with physical senses, embedded in the world, aware of our surroundings without having to attend to them in logical, linguistic, propositional form. It is, in a way, subconscious intelligence: “knowing how” rather than “knowing that.” Believing that we can simply reduce this practical intuition to explicit claims, arguments, or propositions is naive.

Paul Klee, Ad Parnassum, 1932.

Both philosophers undermine the idea that there is a secure, analyzable starting point for knowledge—we find only circular reasons for reasons for reasons and vague pre-rational justifications. This is often seen as a reason for despair. If we cannot “ground” our knowledge in anything secure—if our reasons are circular—why should we have faith that we can say anything at all?

But in my view, Heidegger and Wittgenstein don’t so much demonstrate the limits of rationality as they demonstrate the limits of our theories of rationality. They show only that we cannot fully understand how rationality is doing what it is doing.

Like Nagel, I think this presents us with two options: skepticism or—loosely construed—faith. Either the mysterious structures underpinning our rationality are arbitrary and misleading, or—somehow—they broadly work. Skepticism, which of course depends itself on our having rational reasons for doubt, undermines itself. Thus we are forced to wager that there is something somehow connecting our thoughts with reality.

This idea has emerged in various forms in recent philosophy. Nagel talks about our need for something to play the role that God played for Descartes—something that accounts for the “fit between ourselves and the world for which we have no explanation but which is necessary for thought to yield knowledge.” He continues: “I have no idea what unheard-of property of the natural order this might be. But without something fairly remarkable, human knowledge is unintelligible.”

George Steiner talks of our “faith” in language: the “wager” we make whenever we speak that our words somehow connect with the world—an “act of trust” that is, “in the last analysis, a theological one.” Stanley Rosen talks of “intuition”—of the insight “that leads us to say, ‘I see what you mean!’” He continues: “I flatly deny that the intuition is itself analyzable into an equivalent set of synthetic or analytical statements that render the intuition superfluous. On the contrary, such analyses are guided at every significant point by intuition itself.” Heidegger talks of “that which needs no proof in order to become accessible to thinking.” Leo Strauss talks more plainly of “revelation.”

Indeed, when faced with something as “unreasonably effective” as science—to borrow a phrase from the mathematician Eugene Wigner—it is hard not to see our capacity to comprehend the deepest workings of reality as in some sense “revelatory.” But this needn’t mean revelation of some final picture of everything. Perhaps we are granted insights into a few different aspects of reality, related to one another but not completely continuous. Perhaps, for instance, in addition to objective and subjective, there are other modes of reality, between those two, that we cannot conceptualize, which would be necessary if we were to understand how to get between the ones we can see. It is as if we look out into foggy darkness and see, to our left, one brilliantly illuminated scene, and, to our right, another brilliantly illuminated scene, but cannot see how they might be connected. Surely it is enough to recognize both remarkable truths at once, without having to collapse them into a crude, oversimplified final answer.