Ordering the World: Trade Catalogs as Symbols of Modernization

I like organized like things. “Like” as in “similar to,” being of the same genus. Take two of the posters on my apartment wall. Both are Cavallini papers: one is a rendering of 19 or so cacti and succulents; the other is a display of 17 images of cheese—from cheddar to koboko to gorgonzola. My taste in wall art stems from my love of trade catalogs, a fascinating source type that gives us a glimpse into how societies—particularly those grappling with the meaning of “modernity”—ordered their world.

In the twentieth century West, trade catalogs were advertisements for a company’s products that often featured pictorial elements of products for sale. This was not always the case. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, trade catalogs were mostly (or entirely) list based and without illustrations; they often included “high” items such as books and art. Visual elements slowly emerged in trade catalogs throughout the nineteenth century, tracking with the standard narrative of a post-Enlightenment conception of art as a consumer good and a means of furthering control over nature and the self. The larger number of industries with trade catalogs in the nineteenth century represents the democratization of sale. The modern marketplace was complete by the early twentieth century, where the whole consumable world could fit onto the pages of a neatly bound trade catalog. These mail-order behemoths lend themselves to narratives of modernity as a story of total human control of the built environment, though a straightforwardly linear story of ever-increasing command over more and more of life can obscure efforts at dominion over knowledge found even in the earliest catalogs, which will be examined first.

Even the earliest catalogs show attempts at ordering the world by lists of products. A 1744 catalog of books from Benjamin Franklin is a great example, marking out a large swath of eighteenth-century Anglosphere intellectual culture. Other catalogs in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were similar. An 1820 English auction for Greek vases and a 1795 German Neoclassical illustration of room furnishings (inspired by ancient Rome and Greece) were not intended for those below the highest financial and social station. These were “high” creations meant for the elite; much of what was advertised here was not fungible. Such catalogs illustrate the purported Enlightenment mentality, which prizes rationality, science, and order as prime hermeneutics (interpretive lenses) to view the world.

Catalog illustrations became more and more common during the nineteenth century. The English brass catalog above (from about 1819) is a shift from earlier catalogs in that it is about practical art, not just art only meant to be admired for its beauty or intellectual value. It shows the transition from art as art to art as a manufactured good meant for personal consumption. Due to British industrialization (mechanized elements becoming the means of production), practical art such as brass furnishings could become prevalent in more dwellings. The uniqueness of an ancient vase cannot be found in a factory. With greater fungibility, art becomes more consumable.

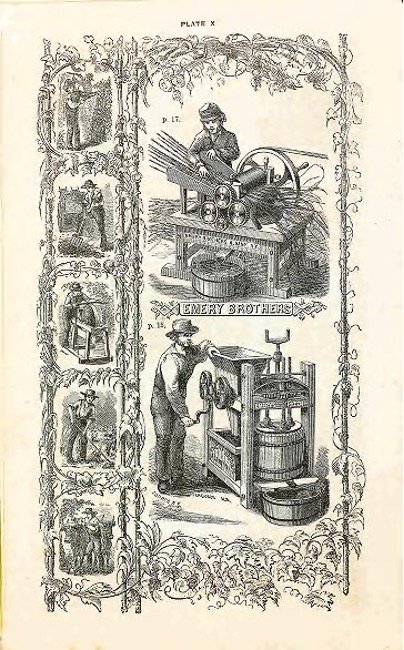

Trade catalogs soon began marketing to the masses. The 1860 farming equipment page from an Albany, New York company depicts implements meant to be used by ordinary people. This and similar texts show how industrialized goods were democratized. The viewer on the farm can see him or herself in these images doing work more efficiently. In this way, human desire was visualized with reference to a price. Additionally, catalogs such as these were meant to serve a wider area. The Albany pamphlet advertises goods for growing cotton, sugar, corn, wine, and cheese. Not all of these crops grow equally well in upstate New York. These documents mark the beginning of a cultural nationalization and homogenization process.

By the turn to the twentieth century, trade catalogs offered a sense of total control over modern life. Ben Franklin had nothing on these mass-produced books on quotidian topics meant for any American, as shown in the 1898 Sears, Roebuck and Company catalog. When advertisements for fortune-telling are within the same covers as Bible ads, one can tell that consumption has become the new object of worship (see pp. 290, 322). Not only was almost every manufactured product imaginable in one of these monumental trade texts, the devotion was meant to be lifelong: “We know that if you buy once from us you will always be a steady customer” (p. 116). Complete mastery was an ideational goal achievable by capitalism. The images of hats, stoves, medicine, and food all provided the viewer with a cornucopia of abundance. Pictures of possible futures became sacramental, as visible signs that pointed to the invisible reality of ordered satiation.

The posters on my wall are meant to evoke a vintage style, but they are really artistic echoes of centuries of attempts to catalog the world, from book lists to agricultural pictures to Sears’ grandiosity. My posters’ ordered collections of plants or cheese are in some ways as pleasing as these trade catalogs are, appealing to the human desire for systematization. But at their best, these posters are more than that. They are successful as art when they evoke wonder and awe for both the natural world and the built world alike. They exceed their purpose when they point to larger truths, such as beauty and goodness. And these posters are seen best through the eyes of gift, with the knowledge that the unsaleable dignity of what is created and made cannot be quantified nor express shipped.

Carl Friesenhahn is a PhD student in history at Syracuse University. He studies the history of meaning and ideas in the United States.