Modernity and the Evolution of Consciousness: Part II

In the previous article, I ended my brief sketch of Owen Barfield’s alternative conception of modernity by hinting at the potential it harbors for a renewal of participation—a rediscovery of meaning in a divinely-minded world. Whereas Barfield used the term “original participation” to refer to the primordial form of human consciousness which featured an experienced unity of observer and observed, he coined “final participation” to refer to the voluntary effort to recover that unity without annulling the process of differentiation (and individuation) which has intervened. To make the potential of “final participation” more explicable, it will be necessary to deepen Barfield’s portrayal of semantic history by further contrasting it with a developmental theory of language that has enjoyed wider currency since the 19th century.

The prevailing theories of Barfield’s time, with early precedent in thinkers like Max Müller, assumed that the first words uttered by human beings merely denoted material things and that it was only later, thanks to some hypothetical poets of a hypothetical “metaphorical period,” that so-called subjective concepts—concepts with no material basis like spirit—accrued to words like the ancient Greek pneuma. Barfield came up with a handy way of identifying the habit of thought which undergirds such theories with the acronym R.U.P.—short for the “residues of unresolved positivism.”Implicit in Müller’s theory is the assumption that the external, material world has ontological primacy over the thinking consciousness which permits theorizing in the first place. But as argued in Part I, semantic history reveals consciousness to be just as primeval as matter—the two have co-evolved. This is evidenced, says Barfield, by the etymological fact that there were no merely material word-meanings prior to the imaginal kind. Müller’s hypothesis thus departs from the facts and exemplifies the hermeneutical immodesty which Barfield refers to as “logomorphism,” or the tendency to project “post-logical thoughts back into a pre-logical age.” By referring to the ancient Greeks as “pre-logical,” Barfield is not suggesting that they lacked all capacity for rational thinking—far from it, as the history of philosophy attests—rather, what he means is that rational activity had not yet become a defining feature in their experience of the world.

A clear indication that rational activity has become a defining feature is when subject and object—inside and outside—become sharply differentiated in experience. If these laws had permeated the thinking of ancient peoples, we should expect to find exclusive reference to material objects and processes in the oldest languages, but instead we find more imaginal meanings the further back we go. The laws of logic were indeed important features of Aristotle’s philosophy, but like Plato, he held contemplative participation in the divine Mind which shines through the appearances of the senses as the highest form of knowing. The Logos (λόγος), for them, was something that belonged to the dynamic fabric of the world—a light in which they could participate so as to render their immediate, albeit dreamy perception of meaning in the world more intelligible. The natural world, as Barfield describes in “The Rediscovery of Meaning,” was experienced as “a series of images symbolizing concepts.” Logic was a feature of the world before it became a power of the individuated mind. For Barfield, the polarization portrayed by semantic history can be read as a gradual internalizationof the world’s conceptuality: first in the perceptual after-images of memory, and, eventually, in their creative redeployment through the symbolizing power of language. “Language,” as Barfield says, “is the storehouse of imagination,” the internalization of the world-Logos. And like the store of memory that helps to forge an inner identity across a single lifetime, language as the storehouse of imagination gradually insulated and thereby facilitated the inward individuation of humanity from our dreaming unity with the life of the whole.

As the internalization of the Word-like character of the world persists, it reaches a point of completion—severing itself from the world’s fount of meaning. The storehouse then becomes a protective enclosure from the influence of that fount, incubating subjectivity in the logical distinctions that increased spatial-awareness affords until the world of objects becomes clarified enough to awaken their polar opposite—self-consciousness. Freedom—from compulsory participation in the wiles of the Homeric gods, for example—was the boon of this bittersweet separation from the world’s living meaning. But the more clarified condition of modernity arises later, when the atavistic holdout of imaginal meaning—resident in early languages—dries up in abstract literalism, when the crystallization of meaning has advanced so far as to modify perception and constrain it to the fixed dualism of subject and object. No wonder Bacon failed to understand Aristotle or appreciate the fact that the Scholastics and other medieval thinkers were fighting to keep the tradition of participatory knowing alive. And yet, as these latter thinkers exemplify, exclusively instrumental science and, later, Descartes’ articulation of dualism, were not the only possible responses. In fact, the express purpose of Barfield’s “Either : Or” essay is to explore how Coleridge’s metaphysics of polarity offers a vital alternative to Descartes’ legacy, especially with his concept of the underlying “tri-unity” of reality. Rather than claim that one perspective is more correct than other, it seems that the very freedom to choose which vision one comports oneself to is what essentially characterizes the modern era.

Barfield’s adventure into semantic history began initially with his phenomenological investigation of poetic diction. His experience was that poetry—Romantic poetry in particular—had the potential to expand perception by rousing the imagination in a way that forged a new unity of self and world. As Barfield would later find, older forms of syntax and ancient words themselves could induce imaginative perception in a similar way. But in contrast to metaphors that are intentionally crafted by individuals, the imaginal meanings of ancient words testify to an experience of the whole before it was sundered. It was for this reason that Barfield insisted on semantic history as a vital means of self-knowledge. The disclosure afforded by the history of meaning can be described as a morphological inversion from, as Barfield writes in Speaker’s Meaning, “the state of active object, correlative to passive subject, to the state of passive object, correlative to active subject.” Whereas, for “original participation,” meaning was given to human consciousness from without by the world as active object, today, as active subjects, human beings now occupy, in Barfield’s words, a “directionally-creator” relation to phenomena. The individual poet literally has to fight the abstract language which conditions the cultural imaginary she inherits by infusing new meaning into it through what Barfield calls “true metaphor”—or poetic diction which reflects participant knowledge. But to glimpse the life of the whole with eyes of renewed participation, a kind of piety is required.

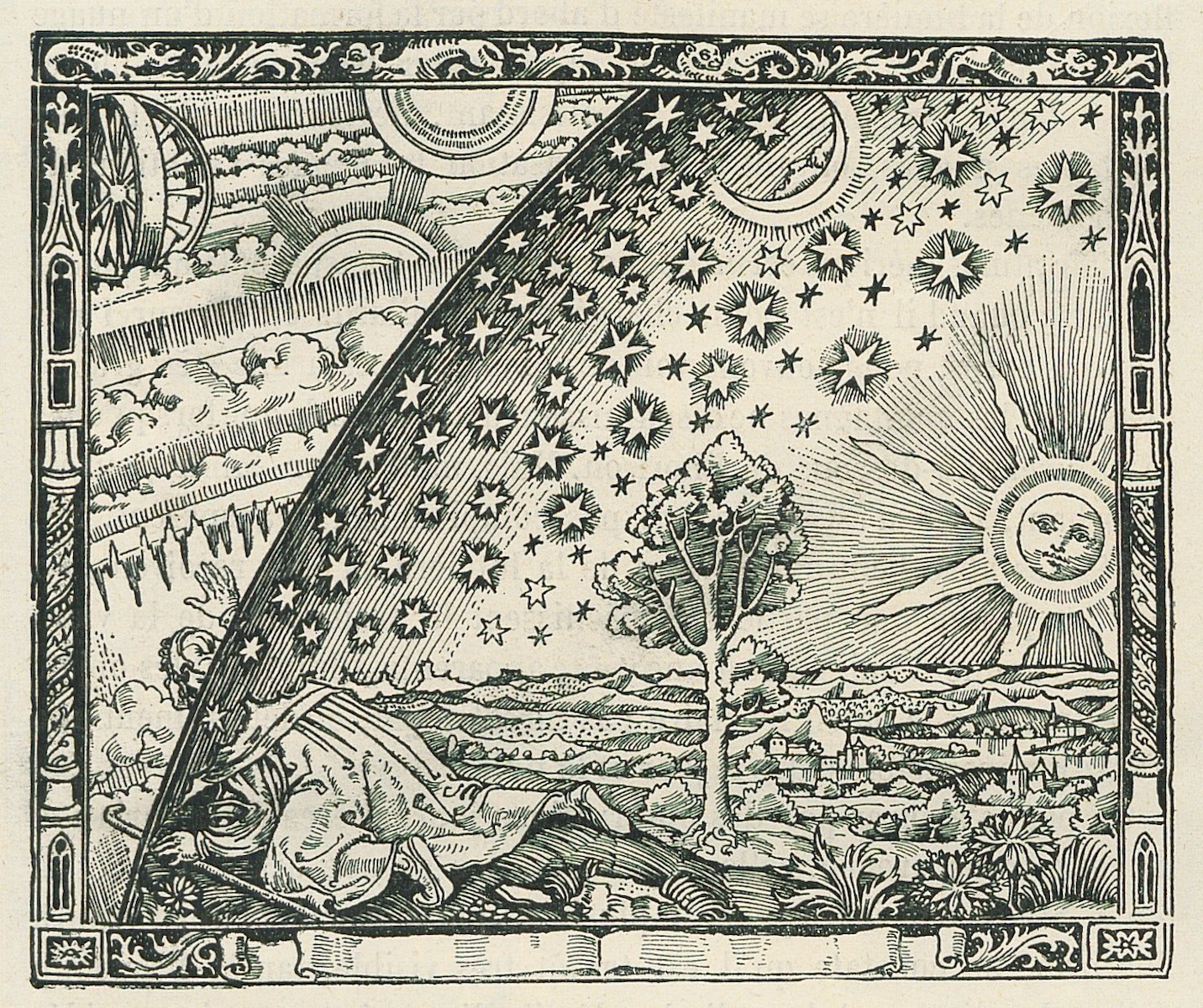

Barfield visualized this entire evolutionary development in the shape of a “U”: From the upper left side of the “U”—the heavenly existence of “original participation”—humanity falls into a state of materialization so dense that the world of spirit can no longer shine through. At the nadir, the perceptual and linguistic process of internalizing the world-Logos—what might equally be described as a process of divine kenosis—reaches a point of completion in the incarnation and passion of the Christ. The self-consciousness and creative agency associated with modern subjectivity are thus read by Barfield as gifts that issue from a sacrifice of the Word made flesh. In the context of Barfield’s metanarrative, modernity becomes a period defined by the freedom of choosing whether to forsake that sacrifice or honor it by participating in the resurrection of the entire world. Honoring it need not consist in any confession or even knowledge of Christ; rather, what is essential is a fidelity to the world as theophany. For Barfield, the alternative—conceiving the world as a collection of objects awaiting exploitation, severed from the love of God—amounts to a form of perceptual idolatry. The poetic transfiguration of our abstract language and opaque imaginaries will be a crucial site for the resurrective activity of “final participation,” but only if living insight is won from the achievement of, as Barfield describes in the preface to the second edition of Poetic Diction, “conscious control of the primary imagination.” Unlike the meaning immediately given in experience for the pre-subjective consciousness of “original participation,” the meaning one is graced to strive for through “final participation” carries the promise of a deeper intimacy—the intimacy of knowing. To quote Barfield one last time: “Men do not invent those mysterious relations between separate external objects, and between objects and feelings or ideas… These relations exist independently, not indeed of Thought, but of any individual thinker… The language of primitive men reports them as direct perceptual experience. The speaker has observed a unity, and is not therefore himself conscious of relation. But we, in the development of consciousness, have lost the power to see this one as one… Thus, the ‘before-unapprehended’ relationships of which [Percy] Shelley spoke, are in a sense 'forgotten' relationships. For though they were never yet apprehended, they were at one time seen. And imagination can see them again.” In terms of the vast cycle of time represented by the “U,” modernity is still near the nadir, gazing up the right-side at a future that bodes of resurrection. Thus, modernity—reframed according to Barfield’s vision as an ontologically real phase in the co-evolution of consciousness and the cosmos—constitutes a period of consequential response to the sacrifice endured at the turning-point of time.

Ashton K. Arnoldy is a Ph.D. candidate and teaching assistant in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness program at the California Institute of Integral Studies. His dissertation is focused on the recuperation of metanarrative in the work of Owen Barfield.