Abolition and Vigilante Justice, Part II

As I sketched in Part I of this essay, HBO’s Watchmen dramatizes the conflict between abolitionist vigilantes and white supremacist vigilantes. Both groups vindicate their actions by appealing to a higher law, but the former is committed to racial justice while the latter primarily seeks to preserve its own power in a racially stratified society.

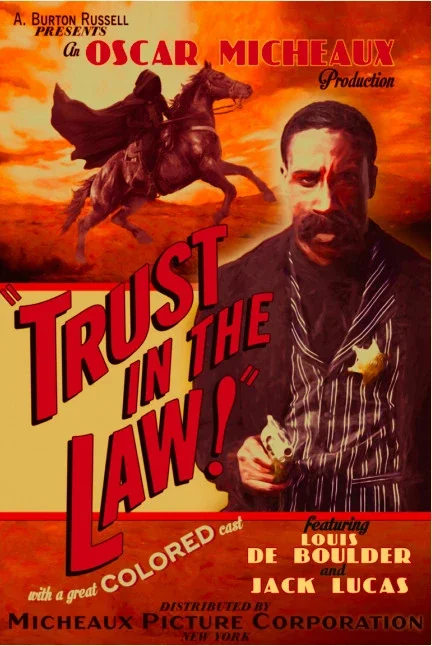

Poster of Oscar Micheaux’s 1921 silent film Trust in the Law!, starring Louis de Boulder and Jack Lucas.

Angela, a law enforcement officer turned vigilante, discovers that she inherited her penchant for vigilantism from her grandfather, Will (Louis Gossett, Jr.)—the original masked crime fighter, Hooded Justice. In the show’s acclaimed sixth episode, Angela relives key moments in Will’s life, from surviving the Tulsa Massacre as a boy to becoming a New York City police officer. Will saw the film Trust in the Law! just a week before his neighborhood was razed in the theater where his mother worked as the pianist accompanying silent films. Trust in the Law! is a fictional biopic of Bass Reeves, the iconic real-life lawman who was born into slavery but became one of the first Black U.S. marshals. In the film, the black-clad Reeves chases a white-clad sheriff. The townspeople cheer when Reeves reveals their sheriff’s corruption. While the townspeople want to hang their sheriff on the spot, Reeves insists that they must trust in the law. In this case, the law and higher law align, as both demand that the corrupt sheriff be exposed and punished for his misdeeds. Yet, this romanticized portrait does not account for how racial prejudice infects institutions.

Opening in theaters the same weekend (November 22, 2019) as Watchmen’s sixth episode premiered on HBO, 21 Bridges features a twenty-first century Bass Reeves in its protagonist Detective Andre Davis (Chadwick Bozeman). Davis leads a manhunt across Manhattan to catch two men who killed several police officers and stole fifty kilos of cocaine in Brooklyn. During the manhunt, however, Davis discovers that the cops themselves have been trafficking cocaine. After a night of bloody carnage, Davis confronts Captain McKenna (J.K. Simmons) in his kitchen. McKenna hopes that Davis will look the other way, but Davis’s integrity is unassailable. When McKenna rationalizes his corruption as an attempt to reduce suicide and divorce rates among his officers, Davis tells him there can be no “blood on the badge.” Davis survives a shootout, killing McKenna in the process.

This scenario repeats the fantasy of Trust in the Law!—that a virtuous Black lawman will be vindicated for uncovering corruption. In the finale of 21 Bridges, a Black detective kills a white captain in his own home. Although the film opens with Davis at an internal affairs deposition, his actions at the end of the film do not provoke his fellow officers’ suspicion. In contrast, HBO’s Watchmen suggests that the insidious forces of white supremacy undermine justice at every turn. In the real world, the “blue wall of silence” ensures that altruistic officers like Davis do not expose their colleagues’ misdeeds, while calls for the public to “back the blue” seek to evade scrutiny of police corruption. The phrase “Who watches the watchmen?” from which Moore and Gibbons got the title for the original graphic novel, poses this very problem of holding those in power accountable.

Graffiti of the phrase that inspired Moore and Gibbons’ graphic novel, 2008 , CC 2.0

HBO’s Watchmen ruthlessly unmasks the fantasy that 21 Bridges perpetuates: that whistleblowers alone will end police corruption. Whereas in 21 Bridges, a virtuous Black detective uncovers a criminal conspiracy within the NYPD, HBO’s Watchmen shows that a Black police officer is nearly lynched by his fellow officers when he threatens their nefarious activities. Inspired by Trust in the Law!, Will (Jovan Adepo) joins the police force. He investigates the mysterious criminal enterprise known as Cyclops, which the show later reveals to be the Seventh Kavalry’s predecessor. The leading members of Cyclops turn out to be Will’s fellow officers, who deter his investigation by hanging him from a tree and only cutting him down when he nearly dies. Despite his parents’ murder during the Tulsa massacre, until this moment, Will still retained faith in the American Dream of liberty and justice for all. Until his fellow officers reveal themselves to be corrupt, vehement racists, Will had still believed in the law’s fundamental righteousness.

When trusting the law fails, Will turns vigilante. Disillusioned and traumatized, Will channels his fury into becoming Hooded Justice. As Batman’s fear of bats inspires his costume, so Will wears a noose around his neck, a hood over his face, and rope around his wrists to become Hooded Justice. At the insistence of his wife June (Danielle Deadwyler), Will puts white cream around his eyes so that the public believes that the man under the mask is white. Will maintains this facade even among the Minutemen, a group of crime fighters akin to the Justice League. Will’s fellow vigilantes are united by a desire to thwart super villains but would balk a racially mixed crime fighting team. As Agent Blake puts it, “white men in masks are heroes, but black men in masks are scary.” While becoming Hooded Justice allows Will to fight white supremacy, this act of racial passing haunts him.

Will (Louis Gossett, Jr.) from HBO’s Watchmen (2019).

Will’s act of passing recalls real-life abolitionist Ellen Craft, who I discussed in Part I. Ellen passed as an infirm white gentleman while her darker-skinned husband William posed as her slave so that they could escape Georgia for Boston. At a crucial juncture in their escape, William and Ellen had to board a train from Baltimore (in the slave state of Maryland) to Philadelphia (in the free state of Pennsylvania). Ironically, the local white racists’ sympathy for Ellen, whom they believed to be an invalid male slaveholder, rather than the able-bodied enslaved woman that she was, enabled the Crafts to enter the train. While the Crafts were nonviolent, they relied on passing to gain their freedom, just as Will’s crime fighting can only be coded as heroic if he passes as white.

By making Angela its protagonist—without passing—HBO’s Watchmen subverts these white supremacist assumptions. As Sister Night, Angela exudes toughness and heroism. She follows an abolitionist higher law in her fight against the Kavalry, whose leader we eventually discover to be a senator and presidential hopeful. The show’s white supremacist vigilantes turn out to be deeply embedded in the nation’s power structures at the highest level.

Although this struggle between abolition and white supremacy is over two centuries old, it is no less relevant to our current moment. One of the most insidious developments of Trump’s second administration has been the aggressive tactics of masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers. By eschewing badges and uniforms, ICE agents belong to the genealogy of white supremacist vigilantes. The Supreme Court rubber stamped ICE’s use of race as a pretext for detaining people. ICE’s recent disregard for due process threatens not only violent criminals or undocumented migrants, but even legal immigrants pursuing the American Dream. Aiming to deport 3,000 people every day while welcoming white South Africans, the Trump administration is enacting white nationalist priorities on a massive scale. We cannot trust in the law when deportations increasingly resemble abductions.

While myriad lawsuits challenge these corrupt policies, this genealogy of abolitionist vigilantism reveals how abolitionists—historical and fictional—have responded to and challenged such injustices. Immigration activists creatively disrupting ICE raids, for instance, recalls the courageous actions of their abolitionist predecessors. In so doing, they disregard legal measures of dubious constitutionality to obey the higher law commanding us to shield the orphan, widow, and strangers among us from injustice.