The Peasant of the Garonne and the Pharaoh Within

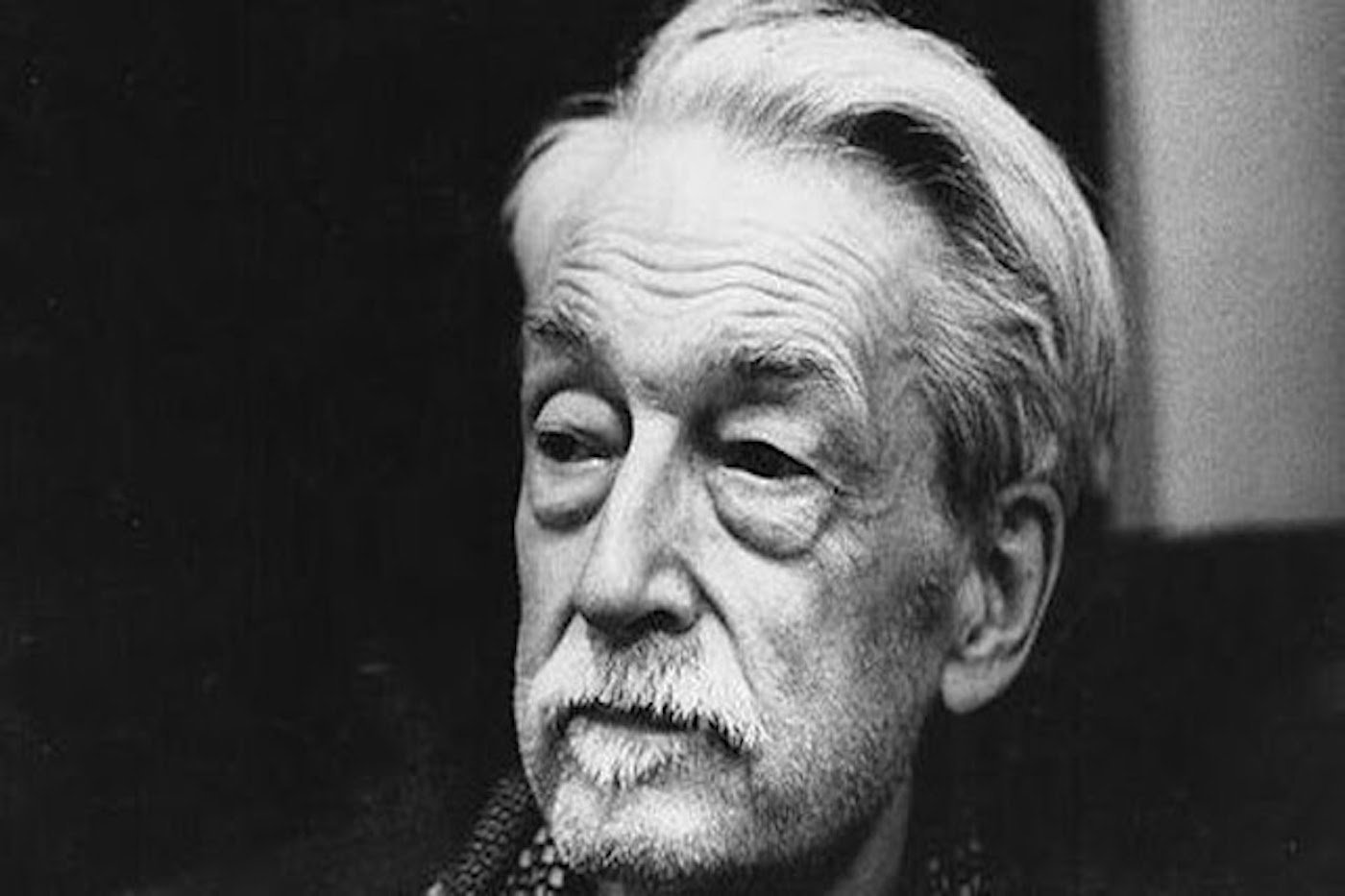

In Toulouse, in the valley of the Garonne, an aging Jacques Maritain witnessed what he perceived to be dangerous modernizing tendencies in the Catholic Church of the 1960s. He responded in his most controversial book with the bluntness of an old peasant. In The Peasant of Garonne: An Old Layman Questions Himself about the Present Time, Maritain is critical of the way he understood the Roman Catholic Church was becoming modern. The book uses the metaphor of a pendulum to explain a crisis of secularization. In the 20th century, this pendulum had swung from what he calls the “masked Manichaeism” of the Church prior to the Second Vatican Council to the post-conciliar mistake of “kneeling before the world.” One mistake called forth the other. In the past, there was a mistaken contempt for the world; but there is now a mistaken over-affirmation of the secular.

Maritain’s account draws on two different conceptions of the “world.” On the one hand, the world as God’s creation is good. It was a mistake for the “masked Manichaeans” to deny that. On the other hand, there is the world understood as that which may either accept Christ and be saved or oppose him and become hostile. The saints practiced contempt for the world as that which opposes Christ. Their contemptus mundi did not mean contempt for creation, nor for the world as that which Christ came to save. Maritain is suspicious of the worldliness and secularism of a Church directed by secular values. This is what he condemns as “kneeling before the world.”

For Maritain, the true importance of the Council was not its call for aggiornamento but instead its universal call to inwardness, to the spiritual life, to contemplation. He remembers that his wife Raïssa had wanted to write a book called Contemplation on the Roads. She believed that the great need of the modern age is to put contemplation on the roads and to give Christians in the world as well as the cloister a way to live in union with God. This is what the world requires if it is not to perish.

Something very similar to what “the peasant of the Garonne” and his wife call “contemplation on the roads” is endorsed in the work of the contemporary philosopher Byung-Chul Han. Han’s cultural critique involves a mixture of influences from Martin Heidegger and Zen Buddhism. What he resists could be described as “the pharaoh within.”

“The pharaoh within” refers to the following concept. The Book of Exodus has been understood in modernity as a paradigm of the political liberation of the oppressed. But there is an older reading. For Origen, Pharaoh symbolizes the carnal mind. Pharaoh symbolizes enslavement by the spirit of this world and inner oppression by worldly desires and concerns. Exodus to liberation in the Promised Land is accomplished by becoming spiritually minded. In his 27th homily on the Book of Numbers, Origen gives an allegorical meaning to each of the locations where the Israelites stopped on their journey out of Egypt. He interprets these locations as metaphors for stages of spiritual progress on the way toward divine union.

Han seems to describe a “pharaoh within” in The Burnout Society. According to his argument, 21st century society is no longer the “disciplinary society” described by Michel Foucault; it is no longer defined by the negativity of prohibitions, by the injunction “No, you may not.” It is rather an “achievement society” with a positive orientation, which affirms, “Yes, we can.” Prohibitions, commandments, and the law are replaced by projects, initiatives, and motivation. But in an achievement society the division between the exploiter and the exploited melts away. We become simultaneously the exploiters and the exploited, master and slave in one, for we exploit ourselves by making work the source of our happiness and our self-esteem. Productivity is no longer something imposed by necessity or external compulsion: it is an act of self-determination. In an achievement society workers become “entrepreneurs of themselves.” For Han, we are becoming a society of Nietzsche’s last men who do nothing but work. We are subjugated subjects who are not even aware of our subjugation.

In an achievement society the repressive power does not repress, but seduces. For what is there to protest against? Oneself? Han cites the conceptual artist Jenny Holzer’s formulation of the paradox of the present situation: “Protect me from what I want.” For Han, depression is the sickness of a society that suffers from an excessive positivity, excessive want. Nothing is impossible in an achievement society. But the achievement subject still reaches a point of exhaustion—and destructive self-reproach. We blame ourselves, not society. No revolutionary mass can arise from exhausted, depressive, and isolated individuals.

In The Scent of Time Han claims that only a revitalization of the vita contemplativa would be capable of liberating us from this burnout society. Contemplation for Han is a lingering with God in loving attentiveness. Being at rest, we become capable of seeing what is at rest. If all contemplative elements are driven out of life, it ends in a deadly hyperactivity. The human being suffocates among its own doings. What is necessary is a revitalization of the vita contemplativa, because it opens spaces for breathing.

The democratization of work in which almost everyone becomes a worker must be accompanied by a democratization of otium, or rest. Han here seems to call for what Bernard Stiegler has called a “new otium of the people.” This otium is the leisure that for Josef Pieper, whom Han also does not name, is the basis of culture. Otium is that precious dimension of human existence that is free from the realm of work. Han refers to Nietzsche who claims that from lack of rest, our civilization is ending in a new barbarism. Never have active, restless people been prized more. Therefore one of the necessary correctives to our society must be a massive strengthening of the contemplative element.

Teaching “contemplation on the roads” may be a way to resist the “pharaoh within” that Han’s work seems to describe—even for the Church in an age when churches are governed by neoliberal criteria of supposed efficiency. In this way we could once again offer our contemporaries what Manuel Castells has called a “resistance identity.” We could dig “trenches of resistance” to ruling norms, build communities of resistance against a burnout society. For, as Origen wrote in his eighth homily on the Book of Exodus, God says to every soul which hastens and strains towards the coming of the parousia, “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt.” For Origen, these words are addressed not only to those who departed from Egypt, but much more to us, who now hear them, if only we depart from Egypt and do not continue serving the Egyptians.

James Lawson is a priest of the Church of England. He is the author of Loving and Hating the World. Ambivalence and Discipleship.