Carlos Bulosan and the Struggle for Asian American Freedom: Part I

America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job and a black body dangling from a tree. America is the illiterate immigrant who is ashamed that the world of books and intellectual opportunities is closed to him. We are all that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant and that lynched black body. All of us, from the first Adams to the last Bulosan, native born or alien, educated or illiterate — We are America!

Carlos Bulosan published these words in a letter in The New Republic in 1943—two years before the end of World War II and three years before the Philippines, then a colony of the United States, would be given its national independence. The letter, written under the pretext of a personal conversation with a mourning widow, represents Bulosan’s critique of early 20th century American society. Bringing a materialist outlook to bear on his colonizer’s nation, he locates the “who” of America on its margins, expanding the nation’s definition of itself to include those who have been excised from its democratic institutions and practices.

Bulosan at his Writing Desk: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, POR0020. Used with permission.

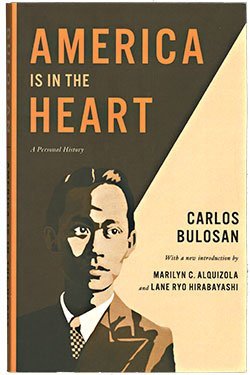

Bulosan, the Filipino American novelist, essayist, and poet, is a canonical figure in Asian American literature, spearheading a tradition of writers whose poetry and prose revel in ambivalence toward American society. He stands alongside intellectuals like Jon Okado, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Maxine Hong Kingston, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Ocean Vuong. His work has been foundational for its documentation of 20th century Filipino migrant life. America Is in the Heart, the semi-autobiographical novel for which he is most known, follows a peasant farmer’s journey from the Philippines to the United States. It is easy to see why Elaine Castillo describes his novel’s scenes as “stark.” Just as Bulosan offers awe-inducing descriptions of the Philippine landscape, comprehension of their beauty is cut off by the brutality of capitalist ownership; just as readers glimpse the intimate relationship between father and son, they discover how exploitation fragments family life. His scenes of life in the United States are equally harrowing. Near-lynchings by white mobs; companions and friends riddled in gambling addiction; failed strikes due to scab labor; and the endless, monotonous, Israel-like sojourn across the American West in search of work. The novel lacks all manner of sentimentality.

Critics like E. San Juan Jr. and Elaine Castillo have encouraged a return to this significant figure of American letters. In my estimation, they are correct. Bulosan’s documentary-like prose, his essays, letters, and novels reveal a mind at work struggling to draw forth freedom’s meaning for colonial wards, farmworkers, and labor organizers in the 20th century. Though Bulosan and his context have long passed, his attention to 20th century Filipino/a American life allowed him to articulate a longing for freedom that is as relevant and enduring today as when Bulosan was still alive.

There is a humanist—and rather liberal—vision of freedom in Bulosan’s writing. Bulosan insists on the dignity and value of life wherever it is to be found; his rhetoric is inclusive, principled, and universal. It cuts across race and class; less so when dealing with gender. His essay Freedom from Want is one of those examples where this expansive vision comes through. Bulosan uses the language of freedom and liberty as the orienting ends of a long struggle initiated by the class of minority workers spread throughout the industries of the United States. “We do not take democracy for granted,” declares Bulosan. He continues:

We feel it grow in our working together — many millions of us working toward a common purpose. If it took us several decades of sacrifices to arrive at this faith it is because it took us that long to know what part of America is ours. … We have moved down the years steadily toward the practice of democracy. We become animate in the growth of Kansas wheat or in the ring of Mississippi rain. We tremble in the strong winds of the Great Lakes. We cut timbers in Oregon just as the gold flowers blossom in Maine. We are multitudes in Pennsylvania mines, in Alaskan canneries. We are millions from Puget Sound to Florida. In violent factories, crowded tenements, teeming cities. Our numbers increase hunger, disease, death, and fear.

Bulosan locates the practitioners of democracy in these migrant farmers, tenant dwellers, colonial subjects, and struggling workers. For Bulosan, freedom has a tentativity and provisionality; it is won through struggle, in need of perpetual enactment. Thus, Bulosan declares, freedom is “not complete unless want is annihilated.”

Throughout his writing, Bulosan appeals to the notion of “America,” a metaphor that at first glance feels nationalistic and idealized. But his intent is just the opposite. Invoking America allows Bulosan to expose the contradiction of the country’s democratic vision. Image after image and scene after scene of Bulosan’s writing is tragic and haunting. Filipinos getting lynched, killed, driven out of town; Filipinos wandering the United States as migrant wards in search of work; Filipinos in the service of capitalist businessmen—this is America. The liberalism of Bulosan is thus deeply disturbed, refined into a critical sensibility by his materialist attention to what life was like on the ground. American freedom exists as both an end and ghost, a possibility and a lack which holds Filipinos, among other minorities, working and living and struggling in squalor.

Bulosan is not alone in his critical appeal to the language of liberalism and freedom. And in the second part of this essay, I will outline what Bulosan’s thinking shares with other modern figures like Søren Kierkegaard and Frederick Douglas, highlighting his enduring relevance for thinking about Asian American freedom today.

Colton Bernasol is a writer and editor based in Chicago, Illinois. You can find more of his writing here.