Forgotten Histories of the Christian Middle East

For centuries, the key motif in Western Christian discourse on Islam was its distance and “otherness.” From the Middle Ages to the 20th century, Western Christians met with Muslims chiefly in the context of war, as was the case during the Crusades or Western colonization. Only in the past few decades have large numbers of Western Christians begun to share everyday communal relations with Muslims. Eastern Christians, by contrast, have shared communities and histories with Muslims for over a millennium. The relationship between Eastern Christians and Muslims is not something we could ever exhaust through one single experience or account; rather, it partakes of the complex variety of joy, routine, and pain that marks all long human histories.

Muslims and Eastern Orthodox Christians share the unique historical experience of each having constituted a large minority population within a great empire of the other: Orthodox Christians under the Ottomans; Muslims under the Russians. In the modern period, imperial conquests and ethno-religious nationalism have seen terrible violence inflicted on each community at the hands of the other, such as the conquest of the Caucasus and the Circassian genocide by the Russian Empire, and the genocides of Armenians and Greeks by the Ottoman Empire. The terrible images and memories produced by these events—both as the result of being a victim or victimizer—have haunted contemporary English-language material on Islam written by and for Eastern Orthodox readers.

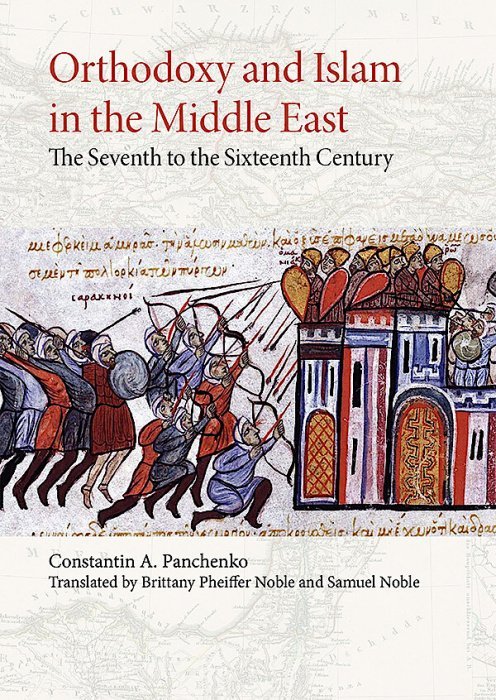

Given this difficult context, Drs. Brittany Pheiffer Noble and Samuel Noble have recently made a historic contribution to the English-speaking Eastern Orthodox community by translating Dr. Constantine Panchenko’s Orthodoxy and Islam in the Middle East: The Seventh to the Sixteenth Centuries, an accessible yet scholarly overview of relations between Muslims and Eastern Orthodox Christians in the medieval Middle East. Panchenko’s analysis sheds new light on four historical periods: the Caliphate (mid-7th to mid-10th century), the second Byzantine and the Fatimid period (mid-10th to mid-11th century), the era of the Crusades (12th–13th century), and the Mamluk period (14th–16th century).

Two dimensions of Panchenko’s analysis stand out to me as particularly worthy of emphasis. First, Panchenko emphasizes that Muslim rule did not by itself lead to Eastern Christian decline. Panchenko delineates two watersheds of acute structural crisis (the first in the mid-8th century, and the second in the 13th century) where natural disasters, environmental degradation, and economic shifts affected the lives of Eastern Christians. His analysis stresses that Eastern Orthodox fortunes were not only affected by Muslim governance practices, but also broader forces such as environmental and economic change. Indeed, during the earliest centuries, systematic persecution of Eastern Christians by Muslim authorities was rare and exceptional. The centralized Muslim empire that succeeded the Arab conquests (the Caliphate) preferred to follow Prophetic precedent and leave Christian populations to their own autonomy as much as possible. However, as this imperial society developed, non-Muslim populations shrunk into ever-decreasing minorities who would be subject to ever-increasing social stigma and legal restriction (especially following the decline of the ‘Abbasid Caliphate).

The second noteworthy aspect of Panchenko’s analysis is his brilliant attempt to chart the development of a distinctly Arabic Eastern Orthodox identity that emerged during the Caliphate (and which endures to the present). This narrative begins with the Eastern Orthodox in Syria and Palestine who retained the faith of the Byzantine church in a new Muslim society—usually referred to in scholarly literature as the “Melkites” (from the Arabic for “royal,” indicating their adherence to the Byzantine church). During the first century of Muslim rule (the Umayyad Caliphate), this community continued to write and practice in Greek and Syriac. But by the time of the ‘Abbasid Caliphate in the mid-8th century, a new Eastern Orthodox culture developed entirely in Arabic that synthesized ‘Abbasid Islamic intellectual culture with Eastern Orthodox faith.

This fascinating community produced great thinkers who wrote Eastern Orthodox theology in the classical Arabic of the Qur’an, and who were in dialogue with Muslim philosophers and intellectuals. The most famous of these was Theodore Abu Qurra (ca. 755-830), the first theologian to elaborate a Nicene-Chalcedonian theological vision in Arabic, and whose theology should be recovered as a vital part of Eastern Orthodox tradition. (Theodore’s works are also available in excellent English translations here, here, and here). Panchenko argues the distinctiveness of this new Arabic Orthodoxy was so strong that when the Byzantines reconquered and ruled Antioch from 969-1084, the community “did not show even the slightest inclination to assimilate” back into Greek Byzantine culture. Instead, these Eastern Orthodox, though newly “rescued” from Muslim rule by their fellow Eastern Orthodox from Byzantium, insisted on developing their syncretic Arabic Orthodox culture even further, epitomized in the extraordinary work of ‘Abdallah ibn al-Fadl (d. ca. 1051).

This book is therefore highly recommended as a window into a forgotten period of Muslim-Orthodox Christian relations. Here the complexities of premodern interfaith relations in general are explored in all their surprisingly human dimensions, avoiding the tragic obscuring of this history that has occurred as the result of modern traumas. The author, its translators, and the seminary press of Holy Trinity Orthodox Monastery in Jordanville, New York, deserve thanks and recognition for this breakthrough contribution. The scholarly quality and accessibility of Panchenko’s work make it of interest to any reader. At the same time, because it is written from a specifically Eastern Orthodox point of view, this book can reconnect these readers with important histories and memories that have long been forgotten.

Phil Dorroll is Associate Professor of Religion at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. His work focuses on Sunni Muslim and Eastern Orthodox theology in Arabic and Turkish.