Hai Zi: Poet and Genealogist of China

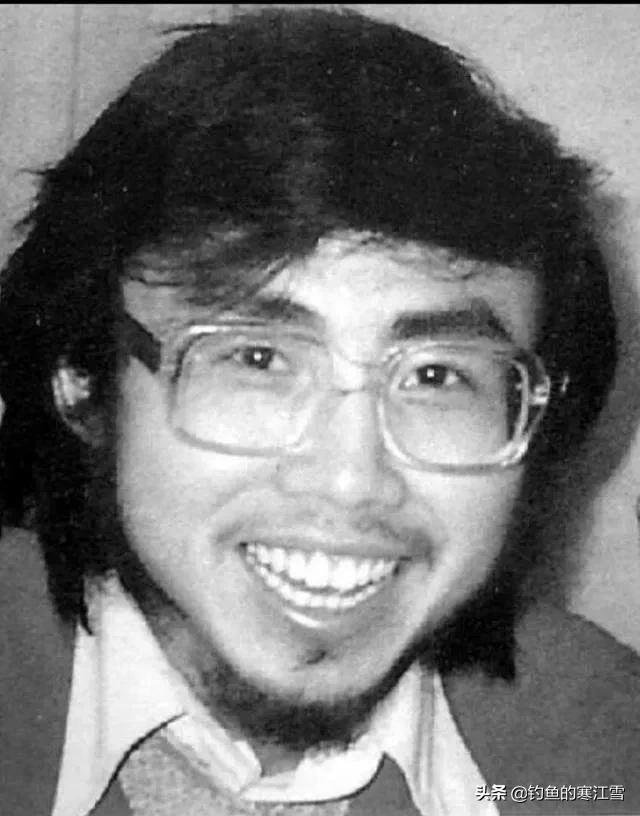

Chinese poet, Hai Zi.

Nearly all of J.D. Salinger’s fiction takes place in the universe of the Glass family, a proto-Royal Tenenbaums cast of eccentric prodigies born equal parts vaudeville and Rimbaud. Seymour Glass, the eldest, is described as a ludic and ludicrously precocious mystic poet and syncretic theologian, disciple from childhood of Goethe and the Gospels as well as Laozi and Hakuin. Seymour enrolls at Columbia University at the age of fifteen and briefly turns the academic world of comparative literature on its head, but the tragic savant’s early adulthood charts a slow-fuse psychological decline through seclusion, institutionalization, and suicide.

Following Seymour’s death, Buddy Glass—second eldest of the Glass children and the implied metafictional author of Catcher in the Rye—inherits Seymour’s collection of 184 unpublished short poems. Finding himself in something of a Kafka-Brod or Hopkins-Bridges dilemma, Buddy debates whether to print or to burn the corpus. Salinger makes the convenient and exasperating decision to refuse to invent so much as one line of Seymour’s verse for the reader. As if taunting us, an effusive Buddy only mythologizes Seymour’s imaginary poetry as a work of unspeakable simplicity and genius, a work which channels with equal gravity the traditions of Li Bai, Bashō, and Dante.

Flawed and occasionally insufferable though Salinger’s short fiction can be, I was from a young age captivated with the idea of Seymour, spending much of my early student life searching, more or less unconsciously, for a real body of poetry that could approximate Buddy’s incredible account. In 2016, I came across its nearest real-life embodiment: not in Salinger, but in Hai Zi.

Though still largely unknown in Anglophone circles, Hai Zi is one of the most important Chinese poets of the last half century. Born Zha Haisheng (1964-1989) in rural Anhui, Hai Zi’s life parallels Seymour Glass’s. Admitted to China’s top university at fifteen, Hai Zi spent his adolescence obsessed with global literatures, devouring shelves of Chinese classics as well as Percy Shelley, Shakespeare, Yesenin, Hölderlin, and the Bible (then only recently made available for reference to students in the Peking University library). Hai Zi, like Seymour, entertained a brief but prodigious foray into academia before suffering acute psychological decline in his 20s, a decline ominously reflected in his later poems (notably his final work, “Spring, Ten Hai Zis”). Both poet-savants were interested in the fusion of Christianity and East Asian spiritual practices: Seymour with Rinzai Zen Buddhism, Hai Zi with qigong. True to Buddy’s portrait, Hai Zi wrote short poems of unspeakable simplicity and genius, poems which invoke Zhuangzi and Confucius alongside Jesus, Nietzsche, and Beatrice.

Hai Zi followed Seymour to the end, taking his own life in March of 1989 by laying himself down on train tracks with a copy of Walden, the Bible, and a cryptic note in a bag at his side. His (mostly unpublished) poems were left in the hands of two fellow writers and classmates, Luo Yihe and Xi Chuan. Luo Yihe died of a brain hemorrhage shortly after Hai Zi, and Xi Chuan was left alone to face the very dilemma of Buddy Glass: to print or burn. Thankfully, unlike Buddy, Xi Chuan decided to publish—and in so doing changed the course of modern Chinese literature.

But my object here is not to speak about Hai Zi’s place in Chinese literary history. I want instead simply to introduce Hai Zi in a capacity in which he is virtually unknown in the West: as one of the most original and surprising genealogists of Western modernity.

The best place to begin with Hai Zi-as-genealogist is his untranslated “Poetics: An Introduction,” an essay which, taken together with his entire corpus of poetry, maps a dizzying history of the concept of modernity from the time of Socrates and Laozi to the present. Li Zhangbin, writing in one of the best (and one of the only) treatments of “Poetics,” interprets the difficult text as an attempt to construct a theogony, a genealogy of the great writers as god-figures. “Theogony” is exactly the right word to describe Hai Zi’s genealogical project. In “Poetics,” Hai Zi mythologizes Laozi and Socrates as the ancient “life-cleavers” or “life-killers,” geniuses of metaphysical bearing who, by their invention of rational inquiry, were able to “pull back the primordial waters” and allow us to walk on land. But, like the fixed land in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra, this progress was not obviously desirable. Despite their best intentions, these life-cleavers fabricated a reductive form of rationality which has slowly torn the threads connecting humanity, nature, and the heavens. The philosophers, Hai Zi tells us, have given us sight at the risk of making us blind. And so in this essay and throughout his verse, he repeatedly invokes the blind poet as our belated savior who can guide our passage back to what Owen Barfield calls “original participation” in nature: “Homer—when will you return?”[1]

Hai Zi’s poetic soteriology will sound familiar enough to any student of the Romantics. This is no coincidence: Hai Zi is forthright about his own influences, famously quipping that he is convinced he wrote Shelley’s poems himself. But Hai Zi’s vision of modernity departs from the Romantics in his account of his own age. Hai Zi construes the twentieth century as the product of a tension between two classes of “saints of modernity,” poetic geniuses who stand in “the chorus of the spirit of the age.”

The first class of genius, characterized by a literal or figurative “self-exile” from society, attempts to inaugurate a “new modernity” through “abstract reason and intelligence.” These figures—who include Kafka, Thoreau, Joyce, Wittgenstein, Cezanne, Darwin, and Freud—variously diagnose the breakdown of modern society and attempt to fashion a new world from the ruins. The second, contending class is of a broadly Platonic-Coleridgean bent, poets who lament our remove from the “primal forces” of nature and call for a more radical return to our origins. These Romantic figures count Van Gogh, Dostoevsky, Shelley, Hart Crane, Schiller, Nietzsche. Hai Zi’s characterizations of these two schools are often oblique and gestural. He tells us that both schools strive to reforge modernity, but it is seldom clear what this might mean. This difficulty is deliberate: Hai Zi insists that whatever diagnosis of modernity he has to offer, it is resistant to paraphrase; it must be understood in the irreducible knowledge of poetry.

Turning to his own poetry, we see that Hai Zi understands his antiphonic “chorus” of modernity as a part of a historical cycle. History is driven in circles by these two kinds of geniuses—roughly speaking, the philosophers and the poets—by whose words the heavens push away and pull back towards Earth like a tide. For Hai Zi, as for Freud, Harold Bloom, or Geoffrey Hill, this cycle is inherently violent and anxious. Hai Zi sees everything in terms of what Fredric Jameson would call a dialectic of period and break, tracing the first historical “break” in history back to Eve’s literal rupture from Adam. But this feud between poets and philosophers is only a blip on the historical radar. Hai Zi, like Seymour, was finally obsessed with an ahistorical vision of a genius capable of transcending the cycle of history, of inaugurating a perpetual “now” (which, as Li rightly notes, is itself an ultimately Romantic notion). These rare geniuses, which Hai Zi calls “Adam-types” or “Kings,” count in their number Homer, Michelangelo, Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe.

“12: Twilight of the Gods/Ragnarök,” the twelfth part of Hai Zi’s epic Earth, narrativizes this quest to become such a genius—not for China or the West alone, he tells us, but for the world. As the poem begins, Hai Zi is drawn towards the ranks of the philosophers, joining Kafka and Joyce in their brilliant but doomed “illusion and exile”:

I sprung up from the primordial King,

Bubbled up—

In illusion and exile I crafted great poetry

As it was all recalled to me:

But he soon abandons this path in favor of the Romantic impulse:

White snow falls ceaselessly into wine

Just as I return to truth

Returning to prehistory’s thrones and dominions

And finally, after a series of markedly Platonic images of prisons and chariots, identifies as an incarnation of Homer:

A singing axe, Homer

Dusk doesn’t not start with you, nor will it end with me

Half is hope, half is fear

Facing the fallen gods of EarthPlease look:

Homer is before us

I am also blind

At the heel of blind Homer

Hai Zi is committed to the anxious question of how Homer, Shakespeare, and the poets made us modern: how our experience of the world is fundamentally mediated by the “ways of seeing” the great poets fashion for us. Hence the cryptic urgency which drives poems like “Dante Arrives Here and Now,” or indeed these lines from the Seven Books of the Sun which describe the birth of poetry:

Nietzsche says now is time.

Now is simply the time.

Thus, poetry begins with his first words.

Hai Zi, like Seymour, is a poet dedicated to—and who would be ultimately undone by—an attempt to create a mythology of modernity. He is a poet as obsessed with the origins of modernity as he is with the challenge of reforging it. “Just as you departed from the company of Virgil,” Hai Zi says, addressing Dante, “so too I shall one day take my leave of you.”

[1] All quotes from Hai Zi’s work are my own translations from Hai Zi Shi Quanbian (The Complete Poems of Haizi), edited by Xi Chuan (1997). Excellent English translations of Hai Zi’s most important short poems are available in collections by Dan Murphy, Ye Chun, and several others. Hai Zi’s long poems and essays remain largely untranslated (though some progress is being made in both English and Italian).

Jake Grefenstette is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Cambridge. He previously studied with Xi Chuan as a Yenching Scholar at Peking University.