Writing After Girard: Part II

The greatness of Cervantes and Proust is to have revealed the imitative laws of human interaction.

If the fiction writer accepts this statement, Girard’s mimetic theory puts him in a tricky spot: because the presence of triangular mimetic desire is a test of literary genius, any writer who fails to include such dynamics in his work thereby reveals his mediocrity. The writer who, after reading Girard, does explicitly illustrate mimetic desire, however, condemns himself to disciple status, thus also confirming his lack of genius.

Is there any way out of this double bind? Four writers who have grappled with Girard’s influence offer some possible escape routes.

Putting Theory “On Hold”

In 2016, playwright Christopher Shinn explained in a short lecture why he teaches mimetic theory to his creative writing students at the New School. “What Girard unlocks,” the Pulitzer finalist says, “is that what truly makes for compelling drama is the symmetry of multiple protagonists battling for the elusive object.”

Set on a college campus, Shinn’s 2013 play Teddy Ferrara explores the events and motivations surrounding a gay student’s suicide. Although the characters see oppressors and victims all around them, their quest for social justice is driven largely by amorous and political rivalry. When one character tells his roommate (who is also his best friend) that he has decided to run for student body president, the roommate reconsiders his initial decision not to run and enters the race. It’s a classic Shakespearean situation, reminiscent of The Two Gentlemen of Verona or A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which friends validate each other’s choices so faithfully that they end up falling for the same girl and becoming enemies.

In a 2016 interview with Shinn, Tom Ue asked about Girard’s influence on the play:

Ue: In your interview with Maura Junius (2013), you discussed the influence of Girard’s mimetic theory and Shakespeare, who ‘follows the logic of unconscious mimetic desire brilliantly’. How do you avoid being oppressed by these ideas?

Shinn: The way to avoid being oppressed by ideas is to always write from the unconscious, in an undirected and free way. That’s not to say that the unconscious is untouched by ideas and ideology, but I think it’s less so than the conscious mind.

Shinn suggests that we bury mimetic desire in the same subterranean layers of the mind where Freud located repressed drives. We do not want to face up to our derivative desire because doing so would entail the wounding realization that we are deeply dependent on others. A writer who overcomes his ego-fueled aversion to this truth, however, gains intimate familiarity with the phenomenon that Girard theorizes. Although ideas may inform such a writer’s work, he is “undirected” and “free” so long as he “follows the unconscious logic of mimetic desire” itself, remaining immersed in the living stream of human experience rather than molding his story to an abstract theoretical framework. Shinn’s ability to put mimetic theory “on hold” while he writes helps to explain why Teddy Ferrara, despite shining a spotlight on adolescent competitive dynamics, is not merely a treatise on mimetic desire and scapegoating. It is also a dead-on satire of school administrators and woke students, an exploration of empathy and its limits, and a study in the complex, overdetermined quality of acts that on the surface seem to admit of a single causal explanation.

Batuman’s Swerve

More skeptical of Girard than Shinn, Elif Batuman is perhaps the only well-known fiction writer to have taken a class with the French thinker, something she did as a Stanford grad student. In her 2010 essay The Possessed, she evokes that experience and the strange effects of learning Girard’s theory while simultaneously behaving in ways that confirmed it. “It was not just mimetic sickness that we had, my classmates and I, but the idea of mimetic sickness, and we had learned it from him.” Being obsessed with a fellow grad student was bad enough, but having him explain your obsession to you in terms of Girardian theory was truly insufferable. And when applied to literature, the ideas felt just as frustrating. Anyone who fully accepts what Girard says about novels, Batuman insists, is compelled to stop writing them.

In 2017, Batuman picked up where her essay left off by publishing The Idiot, a sort of anti-bildungsroman about Selin, an undergrad who falls for an older student, Ivan, and follows him to Hungary over summer vacation. Did Girard’s ideas find their way into the novel? Here is one passage in which the ghost of mimetic rivalry appears in the very act of being exorcised:

Already I was the impetuous one in our friendship—the one who cared less about tradition and personal safety, who evaluated every situation from scratch, as if it had arisen for the first time—while Svetlana was the one who subscribed to rules and systems, who wrote things in designated spaces, and saw herself as the inheritor of centuries of human history and responsibilities. Already we were comparing to see whose way of doing things was better. But it wasn’t a competition as much as an experiment, because neither of us was capable of acting differently, and each viewed the other with an admiration that was inseparable from pity.

While the roommates in The Idiot, unlike those in Shinn’s play, enjoy a mostly drama-free relationship, the “unconscious logic of mimetic desire” does govern the mind games played by Selin and her cagey male crush, who drives her to tears with his erratic communication style. Like a capricious god who bestows or withholds his blessing for unfathomable reasons, Ivan wields the power to plunge Selin into despair or pluck her from the abyss. In an interview Batuman notes that wanting to be like or close to such seemingly superior people is the chief “motivating power” in many classic novels:

For René Girard that’s the main novelistic insight, which is debatable. But it’s definitely a novelistic insight. We do all compare ourselves to other people, and think of other people as being fundamentally different from and less troubled than we are, especially when we’re young. So it makes sense that that would be a big part of [The Idiot].

When Batuman says that mimetic envy is simply a novelistic insight rather than the main one, however, she swerves around the Girardian obstacle, accepting his criterion of literary greatness only up to a point. Discarding the well-worn Balzacian plot of social ascent and disillusionment, her novel finds its motivating power less in Selin’s ambitions than in her sense that the world and people around her, as well as she herself, are a mystery, and that she might stumble on the solution by taking a language class or going on a trip. Selin may get tangled up in rivalry, but all the while she is sifting through her experience like a detective searching for clues, finding poetry in the quirky dross of everyday life.

Separate Jurisdictions

Mahias Enard

Batuman may not be Girard’s biggest fan, but she is more hospitable to literary theory than are many fiction writers. Indeed, a third way of defusing Girard’s influence involves the denial of theory’s jurisdiction over literature. Such a move enabled Mathias Enard to let go of his fascination with Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, which he had at first hoped to harness as a one-stop course in creative writing: “Not only does Girard’s theory go way beyond that,” he would say on French radio, “but my novelistic practice cannot be subordinated to a model, my novelistic practice… will resist my own attempt to theorize it.”

While triangular patterns of desire may be detectable a posteriori in great novels, merely riffing on the Quixote theme of the protagonist who confuses fiction and reality is not a foolproof method for producing a masterpiece. Starting with the limpid concept of triangular desire and trying to work backwards to concrete narrative ignores the elusive, irreducible nature of literary creation, especially the incalculable element of personal investment and memory involved in convincingly evoking a fictional world.

We need look no further than Enard’s Compass, which took the 2015 Goncourt Prize, for evidence that this is the case. The novel concerns the relationship between East and West, just as his earlier, Girard-inflected Street of Thieves did. This time, however, he reverses the perspective: over a single night an insomniac, lovelorn musicologist in Vienna reflects on his life and travels to the Middle East. Enard lived in the region and speaks Persian and Arabic. Having adopted the viewpoint of a Moroccan Muslim enthralled by Europe in Street of Thieves, in Compass he inhabits the gaze of a Westerner obsessed by the East, tapping into his own deepest interests and passions.

What works about the novel defies reduction to a triangle. One of Enard’s themes, for example, is stated through citations from a character’s doctoral dissertation: “what had long been called madness, melancholy, depression was often the result of a friction, a loss of self in creation, in contact with alterity…” Sick, possibly dying, the hero-narrator occupies a position of diminishment, unhappy in love, yearning for people and places beyond his reach. And yet the novel’s exploration of lost time is marked by a wry humor absent from Street of Thieves.

Embracing Epigone Status

A fourth approach to writing after Girard is in some ways the most radical. “I would have felt like an epigone, which is never pleasant,” said Milan Kundera in his 1989 radio conversation with Girard, alluding to his near-miss experience of penning an ultra-Girardian story before discovering Deceit, Desire, and the Novel. The word “epigone” denotes a mediocre follower, a disciple—in short, an imitator. It is “never pleasant” to feel like an imitator because our culture prizes self-reliance, going it alone. To copy is humiliating, an embarrassing sign of inferiority.

That is why the novelist who thinks to himself, “Proust revealed mimetic desire, so I better reveal it too, or I’m nothing but a loser,” is at serious risk of becoming “possessed,” “blocked,” “subordinated,” and “oppressed” by Girard’s ideas. The same egotism that makes him vow to equal In Search of Lost Time will also make him want to do so all by himself, without a helping hand from Professor Girard.

But if, like Kundera, the writer can rest easy, having spotted mimetic desire prior to reading Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, it may be easier for him to dodge this trap, and to feel like a mischievous co-conspirator rather than a hapless copycat. Just a year after his on-air chat with Girard, the Franco-Czech novelist slipped several explicit nods to mimetic theory into his 1990 novel Immortality. “She wanted to be neither her model nor her rival,” he writes of one character’s competitive relationship with her sister. Casting amour-propre to the wind, Kundera goes “full Girard,” embracing the epigone’s role while also underscoring the novel genre’s capacity for intellectual synthesis, its flexible way of incorporating other types of discourse without itself being denatured.

The “Mixed Intelligibility” of Fiction

In Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World, Girard defines his program as the rigorous systematizing of inchoate mimetic patterns extracted from works of fiction. This aligns with Paul Ricoeur’s insight that “the French school of structuralism” attempts “to reconstruct, to simulate at a higher level of rationality, what is already understood on a lower level of narrative understanding, the level brought to light for the first time in Aristotle’s Poetics.” In Ricoeur’s view, structuralism aspires to “a logic of explanation akin to the one governing the exact sciences,” and thus wants to “substitute” this higher level of rationality for the lower level—to replace literary fictions with rigorous theoretical models.

And yet, Ricoeur reminds us, fiction has the power to teach us universals that are not those of “theoretical reason” but are rather “akin to the universals operative in phronesis, ‘prudence,’ in the practical, ethical, and political order.” In other words, fiction possesses an “intelligibility” of its own, one that arises, he says, out of “the formation of plots.” It is “a mixed intelligibility between what can be called thought—the ‘theme,’ the topic of a story—and the intuitive presentation of situations, characters, episodes, changes of fortune, and so on.” This “mixed intelligibility,” he argues, precedes and grounds the second-order intelligibility of theory, not only as a cultural fact, but also “in the epistemological order”—in other words, as a way of knowing.

Shinn, Batuman, Enard, and Kundera all see the appeal of theoretical reason, with its scientific air and conceptual elegance. But they avoid succumbing to theory envy—in other words, they do not buy that the explicit rationality of Girardian thought is somehow more rational or more real than the implicit rationality of fiction.

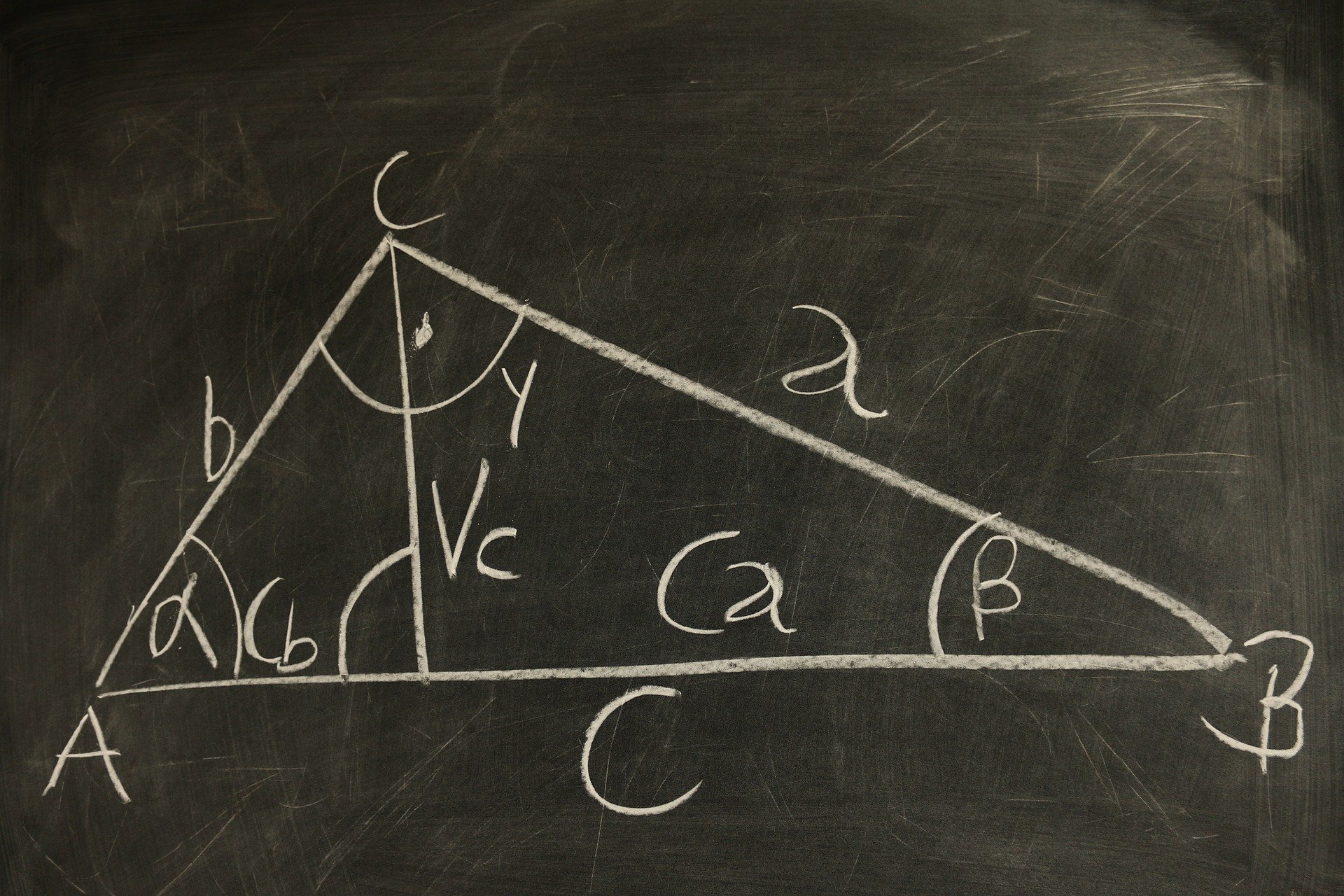

Although Shinn has Freud and Girard at his fingertips, he relies on intuition more than ideas to write his plays; Batuman devises a realism so verisimilar that paint-by-the numbers Girardian triangles would feel formalistic by comparison; Enard creates an alter ego whose suffering likewise eludes encapsulation by a chalkboard diagram; and Kundera, taking the opposite approach, blithely borrows from Girard, an homage befitting a late-career writer who found in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel reason for self-congratulation rather than paralysis.

Against the scientistic snobbery of our time, these writers uphold narrative as a real and important way of knowing, a kind of incarnate reason distinct from the second-order rationality of theory. No doubt it is their confidence in fiction’s intellectual dignity that enables them to accept Girard’s insights as valuable instead of rejecting them outright or feeling thwarted by their astonishing power of reduction.

Trevor Cribben Merrill is the author of Minor Indignities (Wiseblood Books).