Spiritual Abuse and Orthodox Disavowal

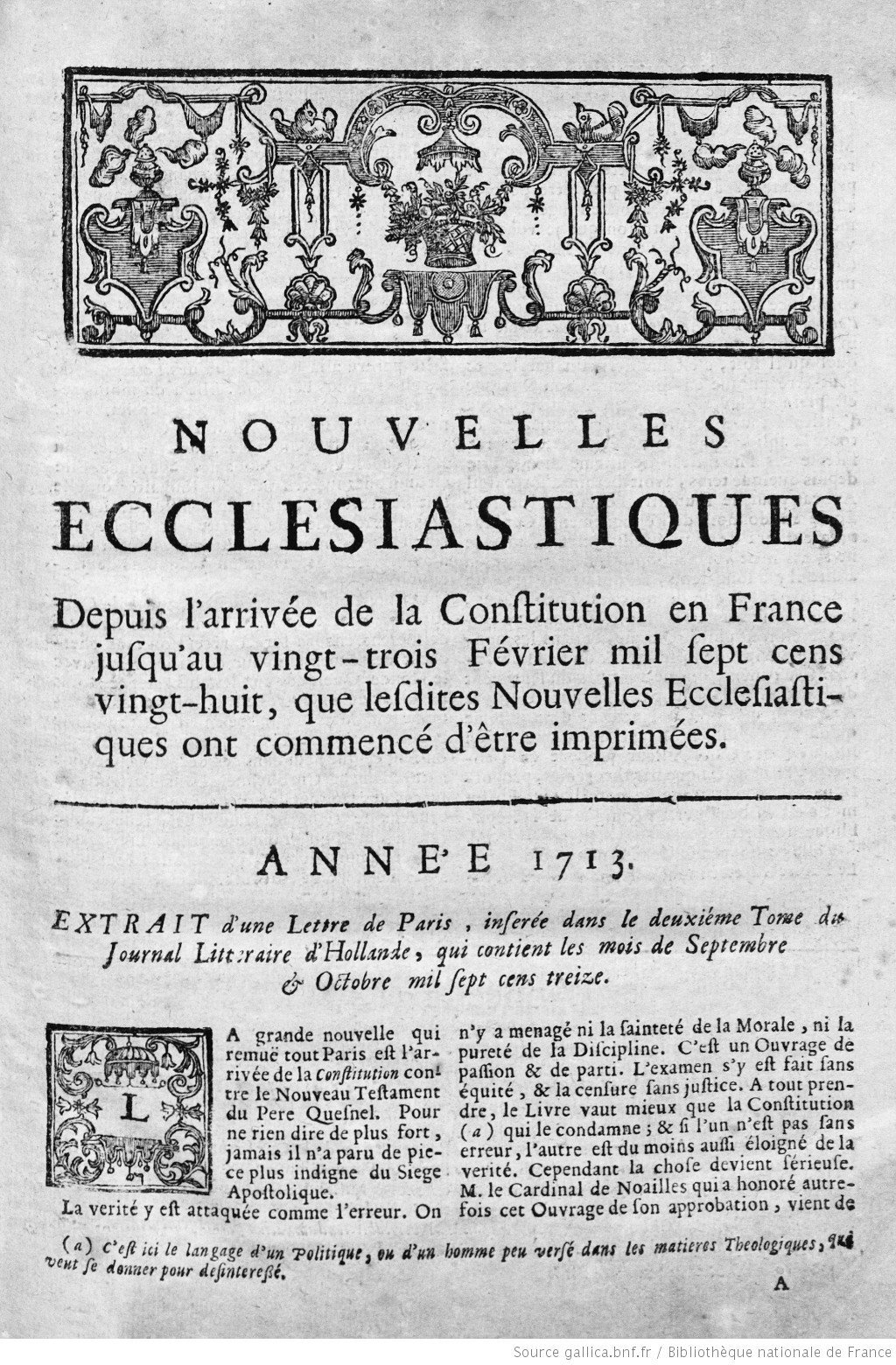

Exemplaire des Nouvelles Ecclésiastiques, quotidien janséniste clandestin

All was not well at the orphanage. Thus reported the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques, Paris’s popular Jansenist newspaper, on August 7th, 1749.* The institution in question, the Hôpital Bicêtre, formed an integral part of Paris’s famous Hôpital général. Its leaders had for some time shown a markedly austere piety and were widely suspected of harboring sympathies for Jansenism. This theo-political tendency, which united a hyper-Augustinian theology of grace with both moral rigorism and Gallican ecclesiology, had been condemned by Clement XI in his 1713 papal bull, Unigenitus. The bull ignited a firestorm throughout the French Catholic church. Over the next several decades both royal and ecclesiastical authorities pursued an aggressive campaign against Jansenists and their sympathizers. Starting in the late 1740s, Archbishop Christophe de Beaumont of Paris implemented a policy denying communion and last rites to anyone who could not produce a billet de confession, a signed statement of adherence to Unigenitus. The Refusal of Sacraments controversy, as it came to be known, entangled ultramontane Church authorities with state officials of the Parlement of Paris who sympathized with Jansenism and Gallicanism. But the controversy was not limited to the heights of Church-State relations.

The Nouvelles ecclésiastiques arose in 1728 to document Jansenist grievances and push for the repeal of the bull. The Nouvelles was unusual in a few different ways. First, although it was an illegal publication—its composition, editing, printing, and dissemination were all clandestine—it was nevertheless one of the most popular newspapers in France. It also paid attention to ordinary people in a way that few if any other publications did at the time. This practice came from the conviction of many Jansenists that the only way to testify to the persecuted “Truth” was to appeal to “public opinion.”

This attention to the menu peuple appears in the report of the 7th of August, 1749. According to the report, the Archbishop had appointed chaplains to the Hôpital Bicêtre who clashed with the Rector and the other Governors. The Rector resigned bitterly in 1746, only to be replaced by an ultramontane priest who began by targeting the “Enfants du Choeur,” that is, the fourteen orphans living in the Hôpital Bicêtre. This trend continued under a third Rector named M. de Malbosc, who took charge in 1747. After only fifteen days in office, Malbosc demanded all the orphans’ billets de confession from their supervisor, the Maître de Choeur. The Nouvelles commented that Malbosc, who was in charge of thirty priests and had the care of over 15,000 souls, nevertheless exhibited a singular “solicitude” for these fourteen children—“but only to destroy them.” Malbosc forbade the orphans from confessing to any priests outside the Hôpital chaplaincy and conducted an inquiry into their reading materials. He found such offensive works as the Bible in French, the Jansenist Catéchisme de Montpellier, and a prayer to the Deacon François de Pâris, a popular Jansenist “saint.” The Nouvelles then reported what the orphans themselves said to their Rector:

“Oh, Sir,” said these poor children, putting forth great cries, “is that what you say to us, that we will find in you ‘a good father and a good confessor’? You rip out of our hands the Word of God. You want us to make our first Communion, and you take away the books that prepare us for it. How can we have confidence in you?”

It is unclear how much of this remonstrance is fanciful. The Nouvelles, though always biased, generally did not resort to fabrication. Moreover, as the report shows, the children’s complaint was not without effect: “With the cries and tears of the children not ceasing, the Rector changed color several times and abandoned the visit, or better yet, the pillage of the Books.”

This brief scene points to the intense sense of harassment felt by many under the regime of Archbishop Beaumont. Yet the paradigmatic drama in the Refusal of Sacraments controversy was not the removal of books, but rather the deathbed battle over last rites. The Nouvelles frequently covered such episodes. A fourteen-year-old boy, close to death, was shriven by one of the chaplains. As the Nouvelles relates, the priest focused not on the ordinary sins, but on whether or not the boy accepted the bull Unigenitus:

The Priest torments him and turns him over, tires him, menaces him, comes again several times to make him at last succumb, and to give him Absolution, in forbidding him, under pain of mortal sin, to tell this to his Governor . . . In communing him, he had him recite, word by word, the very same abjuration that we demand of the Protestants who return to the bosom of the Church, and added to it a formal acceptance of the Constitution [Unigenitus], in making him place his hand on the Holy Gospel.

The unscrupulous priest left, victorious. But when the house Governor visited the dying boy, he found him “sad, dismayed, sinking into his bed to hide his tears.” The Governor asked what happened, and the orphan could say nothing, for fear of committing mortal sin so close to death. We can sense his trauma at having been made to transgress his conscience. Eventually, another official at the Hôpital induced him to talk. He gladly retracted his submission to the bull. But then, the priests returned and the whole rigmarole started again with a dramatic confrontation. As the Nouvelles reports, “‘You are a little wretch,’ [said] the Priest, more wretched than him.” To which the boy answers, “I made [the retraction] in good faith to put my conscience at rest, and no one forced me.” Over the years, the Nouvelles would report many more such scenes.

In confronting these largely forgotten stories from the eighteenth century, I am reminded of a concept which has become increasingly important in our own times: “spiritual abuse.” Although varying definitions of spiritual abuse abound, most include a coercive pattern of behavior that intimidates, threatens, or otherwise harms someone by using religious or spiritual categories. This concept has come to the fore in the wake of the child sex abuse scandals in, among others, the Catholic and Southern Baptist churches, as well as recent examinations of scandals like those that engulfed Mars Hill Church, Silverstream Priory, and other faith communities. Whatever else it may be, the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques is an archive of trauma. It presents cases that, were they to transpire today, would likely earn the title of spiritual abuse. Deathbed harangues, emotional blackmail, fierce tirades, personal threats of damnation, unhallowed graves. Even accounting for the highly partisan nature of these accounts, the stories and voices we discover there pose meaningful questions for the historian, the historical theologian, and the concerned Catholic.

I wonder to what extent we can fruitfully apply the concept of “spiritual abuse” to the early modern world? Some historians—including Ulrich Lehner, Hubert Wolf, Zeb Tortorici, and Dyan Elliott—have come close to this point even when they haven’t used the term. What kinds of new questions can we ask by bringing this concept to bear on our inquiries? Do the gendered patterns of spiritual abuse we find in contemporary faith communities map onto early modern cases? How was the emergence of modernity itself tied to cases of spiritual abuse, whether within or beyond Catholicism? To what extent can we isolate spiritual abuse as a discrete phenomenon, apart from other forms of coercion? And most importantly, can we use the term without telescoping our subjects’ agency into our perception of their victimhood?

The Jansenists are helpful to think about these questions, precisely because they are not like other “heretics” in a few important respects. First, they died out—there are no real Jansenists left today. Second, they left behind a copious archive of print and manuscript sources, some of which are freely available online. And third, we have vivid records of abusive scenes like those that played out in Bicêtre, where agents of the ultramontane Church coercively imposed “orthodoxy” upon the sick, the dying, and the vulnerable. These traits set them apart from ostensibly “heretical” communities that still exist and can defend themselves, those whose writings we know only through their opponents’ polemics, and those whose condemnation remains largely accidental to the character of Catholic Christianity. To point out discrete cases of pre-modern or early modern “spiritual abuse” is one thing. To locate it within the very process by which the Catholic Church established the terms of its own orthodoxy in modernity is quite another. In a very real sense, the ultramontane Catholicism that emerged triumphant in the wake of the French Revolution was intrinsically anti-Jansenist and anti-Gallican, culminating in the dogmatic definition of papal infallibility and universal jurisdiction at Vatican I.

Destruction of the monastery of Port Royal

As I have written elsewhere, the Jansenists have long been subject to an “ultramontane damnatio memoriae.” They are known to most Catholics primarily through myths about sex-obsessed Irish clergy or unsmiling nuns who hated the Sacred Heart. They have fallen under the orthodox disavowal by which all so-called “heretics” become immutably estranged from an imagined, pristine core of the Church. To be an orthodox Catholic today is to buy into this disavowal, confirmed by papal bulls and the acts of ecumenical councils. It is, in short, to side with the spiritual abusers of the 1740s and 50s, or at least to make that abuse illegible and illegitimate. For those of us in the Church of Rome, this invisible complicity should disquiet us. Their spiritual trauma has become the price of our orthodoxy. Thinking more seriously about how the construction of modern Catholic orthodoxy depended upon similar instances of spiritual abuse throughout history can help both theologians and ordinary Catholics better grapple with the Church’s implication in systemic sin. But perhaps that is the task of history, so like that of the Gospel—to disquiet the living with a persistent presence that rises from the dead.

Note: An extended selection from this report will be appearing in From Port-Royal to Pistoia: A Jansenist Anthology, a volume of Jansenist primary sources that I am presently co-editing with Shaun Blanchard. This text will be the first major anthology of Jansenist sources in English translation.

Richard Yoder is pursuing a PhD in History at Penn State University, where he specializes in early modern religious history.