On Divine Space

Christ’s College, Cambridge

Henry More had an odd idea. I like to imagine it occurring to him during one of his strolls through 17th-century Cambridge, perhaps at dawn. Horse-drawn carriages plow by; wind is channeled toward him through ancient, stone alley walls. Around him, cooks, cobblers, carpenters, students, soldiers, prostitutes, professors, butchers, and fisherman all pass through time and space to get from point A to point B. Pushing past colorful characters and ripe aromas of the town market, More suddenly finds himself drenched in shadow, with King’s College Chapel blocking rays of sunshine that had sprinted through millions of empty miles to reach him. Perhaps it was on a morning such as this that More began to think about space as something he was walking through.

Most famous today for his central role among the Cambridge Platonists, More exerted a tremendous amount of his intellectual energy pondering the nature of space. More’s philosophical inquiries led him to several important conclusions. First, whatever space is, it must be something invisible. He observed the simple fact that while we can see things in space, we cannot see space itself. We can see the knife with which the butcher chops, but not the space in and through which he chops. We witness the horse buck its rider, but no one has witnessed the space in and through which the rider is bucked. Space encompasses everywhere and everything that is seen, and yet itself remains unseen, hidden, veiled. The visible, for More, is housed by the invisible.

More also concluded that space must be immaterial. Matter exists in space, and yet the space within which matter exists is not itself material. If we try to reach out and grasp it, space slips through our fingers. Matter competes for location: one material atom displaces another, just as a horse carriage displaces an unlucky pedestrian. Space, however, does not compete with material objects for room in the universe: it allows them to exist within it. Thus, the material is housed by the immaterial.

Third, More realized that space must be infinite. For—as Lucretius argued—if we imagine a wall at the end of space, what would happen if one were to throw a javelin over that wall? Must there not be space on the other side as well? Any conceivable “wall” must itself exist within space, thus proving (by definition) that the thing which the wall is supposed to hedge cannot be hedged at all. There can be no finite limit to the universe, and so space must be infinite.

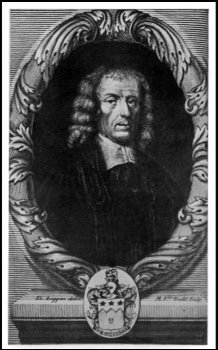

Henry More

More’s sense of space as something invisible, immaterial, and infinite may have a certain intuitive appeal. Beyond these characteristics, More’s account of space is more difficult. His fourth conclusion was that space must be absolute. A classic illustration of this attribute runs like this: imagine that someone shoots an arrow straight up in the air. Does the arrow go straight, or does it curve along with the motion of the earth? If you were the one who shot the arrow, it would seem to go straight up. But what do you know—you’re foolish enough to stand directly under a soon-to-be falling arrow! While the arrow may seem to go straight from your perspective on the ground, we know that the earth is actually spinning, and the arrow curving along with it. So which one is it: does it go straight, or does it curve? More argues that without an absolute space in which the arrow is objectively located, there is no real answer to this question, and we risk being left with only relative realities: one reality where the arrow curves, and one where it goes straight, with no underlying thing-in-itself that reconciles the two perspectives. For More, space must be absolute, or else all of reality is relative.

Moreover, More understood space as omnipresent. For—as we saw in his imagined stroll through 17th-century Cambridge—we cannot go anywhere except in and through space. Where can we go to hide from space itself? Where can we flee from its presence? If we go up to the heavens, it is there. If we make our bed in the depths, it is there. If we rise on the wings of the dawn, or settle on the far side of the sea, even there space clutches, and contains, and permeates us. Space is the one thing that remains wherever we go, and the very thing that allows us to go anywhere at all. Space is omnipresent.

In this sense, space is something deeply immanent and near. Space is closer to us than we are to ourselves—it is equally present with and within every piece of us. Our blood pulses through the open and caverned spaces of our heart. Even the “occupied” bits of our body are themselves occupying space.

And yet, despite this deep immanence, space remains transcendent. That is, despite its nearness, space transcends matter. As we discussed, space is not physical or material in the way that other things are—it cannot be grasped or controlled or experimented upon. Space is not part of God’s material creation but is rather that within which material creation exists. Thus, More’s space successfully balances immanence with transcendence. From the vantage of the created order, space is omnipresent—and yet, unlike anything else in the universe, it remains simultaneously invisible, immaterial, absolute, and infinite. Angels, More reasoned, might meet one or two of these criteria; but only space and God meet them all.

Perhaps stopping with a gasp and blocking foot traffic on the (then newly constructed) Clare College Bridge, More realized that he was thinking about space in the exact same way he thought about God. God is invisible. God is immaterial. God is infinite, absolute, and transcendent, while remaining immanent and omnipresent. All in all, More came up with nearly twenty descriptions of space that also applied to the divine. So he posed the inevitable question: what if space is, in some sense, divine?

More reasoned that if God is somehow linked to space, this would allow God to be truly present while remaining immaterial, thus upholding the creator-creature distinction. God would be deeply related to us but would not be identical with us, just as space is distinct from the objects occupying it while remaining deeply present and related to those objects. Space is not part of creation but that which houses creation; it is not physical, but metaphysical. This would allow God to be genuinely near, immanent, and omnipresent, while still maintaining the classical transcendence of the Judeo-Christian God (and, crucially, avoiding the pantheism of Baruch Spinoza).

More’s divine space might have remained just an eccentric idea. But it just so happened to take the fancy of his fellow Cambridge don, Isaac Newton. Newton baked this notion of absolute, divine space into the very foundations of modern science, quietly wedding physics and metaphysics. For Newton, the motions and locations of matter are real, objective, and primary (in a proto-Lockean sense) because they occur within the absolute and unchanging framework of divine space. This crucial nexus of influence is not something we usually find in popular accounts of Newton’s legacy. But there is a real genealogical case to be made that the solidity of the modern scientific world picture may have been unwittingly grounded upon a theistic metaphysic.

These theological foundations for modern physics were shorn off during the 19th century, with modern physics itself relativized by Einstein in the 20th. However, some recent philosophers—including Richard Swinburne, William Lane Craig, and John Lucas—have forcefully argued that an absolute (or at least metaphysical) understanding of space and time remains consistent with the observations of relativity. Yet while many have allowed this possible return of absolutes to reshape their theology and philosophy of time, few seem to have realized its potential for rethinking God’s relation to space.

This is exactly what I explore in my upcoming book, Space God: Rejudging a Debate Between More, Newton, and Einstein (Cascade, 2023). Join the mailing list on jdlyonhart.com to be notified upon release, and discover if divine space still has any merit in the 21st century: a Space God for a Space Age?

JD Lyonhart is a Fellow at the Cambridge Centre for the Study of Platonism, an Assistant Professor of Theology and Philosophy at Lincoln Christian University (lincolnchristian.edu), and a Co-Host of The Spiritually Incorrect Podcast (spirituallyincorrectpodcast.com).