The Gilded Age

“Now you need to know we only receive the old people in this house, not the new. Never the new. The old have been in charge since before the revolution. They ruled justly until the new people invaded…. My mother, your grandmother, was a Livingston of Livingston Manor, and they came to this city in 1674. You belong to old New York, my dear, and don’t let anyone tell you different. You are my niece, and you belong to old New York.” So says Agnes Von Rijn to her niece in the first episode of The Gilded Age, a drama by Julian Fellowes of Downton Abbey fame. Here, Fellowes plays upon the successful formula of Downton, but shifts the action thirty years earlier across the pond, to Gilded Age New York. It’s a great concept, set in an often-overlooked era of American history.

Much of The Gilded Age will be familiar to Downtonians: the upstairs-downstairs drama, the avoidance of scandal and the importance of public opinion, and realistic fictional characters navigating and responding to real-life historical watersheds. Most interestingly, both shows are about how different characters respond to social change, some embracing or even encouraging it, others defying it.

In addition, most of the Gilded Age characters have a Downton Abbey counterpart. The Gilded Age’s Marian Brook (played by Louisa Jacobson) seems a callback to Downton’s Lady Mary Crawley, not only for their youth and natural willfulness, but as the characters central to the dramatic action. I fondly remember Downton’s Isobel Grey and the Dowager Countess (played by Penelope Wilton and Maggie Smith, respectively), bickering over the changes they see around them. The Gilded Age has a similar pair: two sisters named Ada and Agnes (played wonderfully by Cynthia Nixon and Christine Baranski).

To me, The Gilded Age’s success depends upon it gaining back a large portion of its loyal Downton Abbey viewership, but what percentage of Downton viewers would be interested in a Downton Abbey outside England? To ask this question a little differently, how much of Downton Abbey’s appeal comes from its English setting? As a thought experiment: could the show have been set in mainland Europe or some kind of fantasy country, all else kept the same, and still have gained the fanbase it did? No doubt it would have been just as well crafted, but I can’t imagine this other Downton achieving the success that the show gained in the United States.

One of the critical things about this shift in setting is that the United States of the Gilded Age had no established nobility: no counts, no formal dukedoms, no earls passing on their titles and lands for hundreds of years, generation after generation. In England this created a caste system that was comparatively stable. Of course, noble families could lose their fortunes, and their degree of influence could wax or wane, but the established rules of nobility meant that for centuries, who was “in” and who was “out” in society was (with exceptions) fixed. Of course, by the time the events of Downton Abbey rolled around, these institutions were on the decline. Part of what makes Downton so compelling is to see how these different characters, both noble and proletariat, deal with that change.

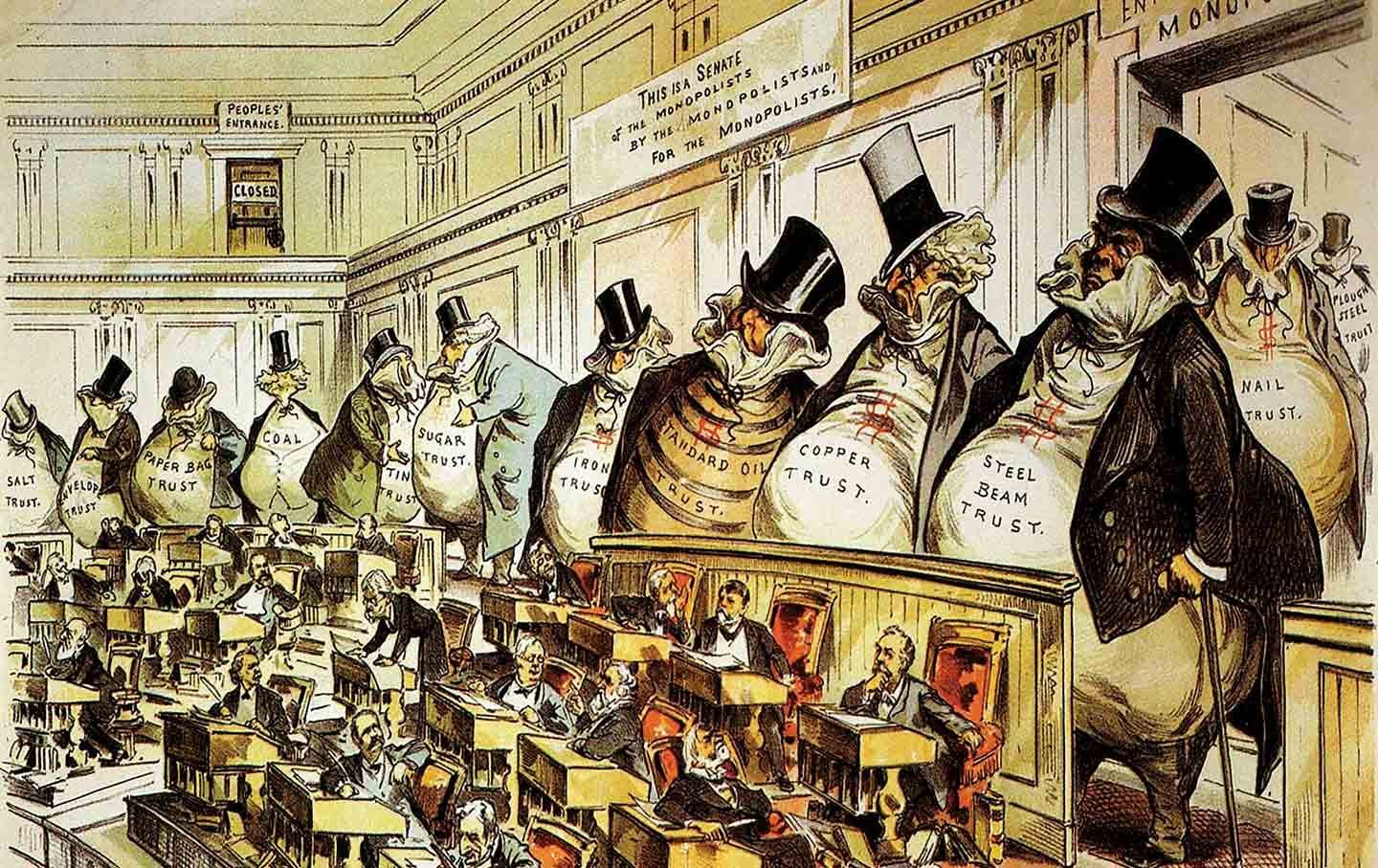

The United States, however, did not have such an established nobility, and this made the upper echelons of society, the “who’s who,” necessarily more complex and fluid. All of this came to a head during the Gilded Age, in which the wealthy families who had held sway for generations dating back to the American Revolution, the so-called “old money,” were challenged by “new money” families, many of whom had only just made their fortunes in economies that were rapidly industrializing.

The Gilded Age dramatizes this conflict well. On the one side, the old money is represented by the aforementioned Ada and Agnes (Nixon and Baranski), their family, and their circle of friends, and also includes real-life tastemakers Caroline Astor and Ward McAllister (played by Donna Murphy and Nathan Lane). Overwhelmingly, these rich “old money” families—families that could trace their family histories back to the Mayflower, so-called “Boston Brahmins,” who were overwhelmingly what we would today call WASPs—fashioned themselves after the old world English nobility, families like Downton’s Crawleys.

What this means is that The Gilded Age’s uncanny resemblance to Downtown has as much to do with the show’s attempt to appeal to their Downton-watching, American Anglophile audience as it does the historical Anglophilia of its Gilded Age characters. The American “nobility” created their lives in conscious imitation of the British nobility, in everything from their social rules, their sense of who is “in” and who is “out,” to the regulation of their households. In a memorable sequence halfway through the season, Bannister, the butler of one of the old-money households, educates another butler how to set the silverware in “the English way,” using this phrase as a social trump card. If it is not “the English way,” it isn’t anything at all.

While the old money families liked to pretend that their caste was as closed and fixed as that of the British nobility, with no title to fall back on, but only money to distinguish them, they were necessarily challenged by others who came into great wealth. In The Gilded Age, the “new money” is represented by the Russell family, with a power couple played by Carrie Coon and Morgan Spector, at the helm of New York society. The Russells are fictional versions of the families whose industrial innovations caused almost unheard-of wealth in the Gilded Age, families with familiar names like Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt. Much of the drama of the first season centers on the Russells’ attempt to get their foot in the door with the wealthy elite, and the attempt of the old-money families to shut the Russells out from any social recognition. The New World questions concerning who is “in” and who is “out” are even grayer and hazier than anywhere in England.

All-in-all I liked this show and am excited about its future, but I have to admit that there was something a little dull about this first season. Part of the excitement of the first season of Downton was seeing how the aristocratic Crawley family struggled to maintain a decorous, outward appearance in the midst of real, private family scandal. The Gilded Age has the opposite problem: it seems the show’s creators worked overtime to depict the “genteel” lifestyle of these American elite, almost as if they were anxious to convince their audience that America’s elite had once been comparable to the British aristocracy. As a result, the drama is more subdued, and less seems to happen in the ten episodes of Season 1 of The Gilded Age than happens in the six episodes of Season 1 of Downton.

Encouragingly the show has been renewed for a second season, and I’ll admit that much of Season 1 feels like a grand prelude or setup, to the kinds of historical events the show can explore through the lives of its characters. I hope that, like Downton Abbey, The Gilded Age runs for enough seasons for it to do justice to the events that make this era of American history so fascinating.

I am concerned, however, about whether the show can develop an audience quickly enough to renew for even a third season. For me, it all comes back to the question of whether audiences would be interested in a Downton-esque show outside of England. Based on the number of Americans I know who are die-hard Anglophiles with a certain distaste for all things American—people who have read every Dickens or Austen novel multiple times but who haven’t once picked up a book by Twain, Melville, or Faulkner, and have no desire to—I am skeptical that the show will succeed. Indeed, modern American viewers seem to suffer from the same bias as The Gilded Age characters themselves: if it isn’t the English way, it isn’t anything at all.