In Hope of Bulkington: Moby Dick and American Doom

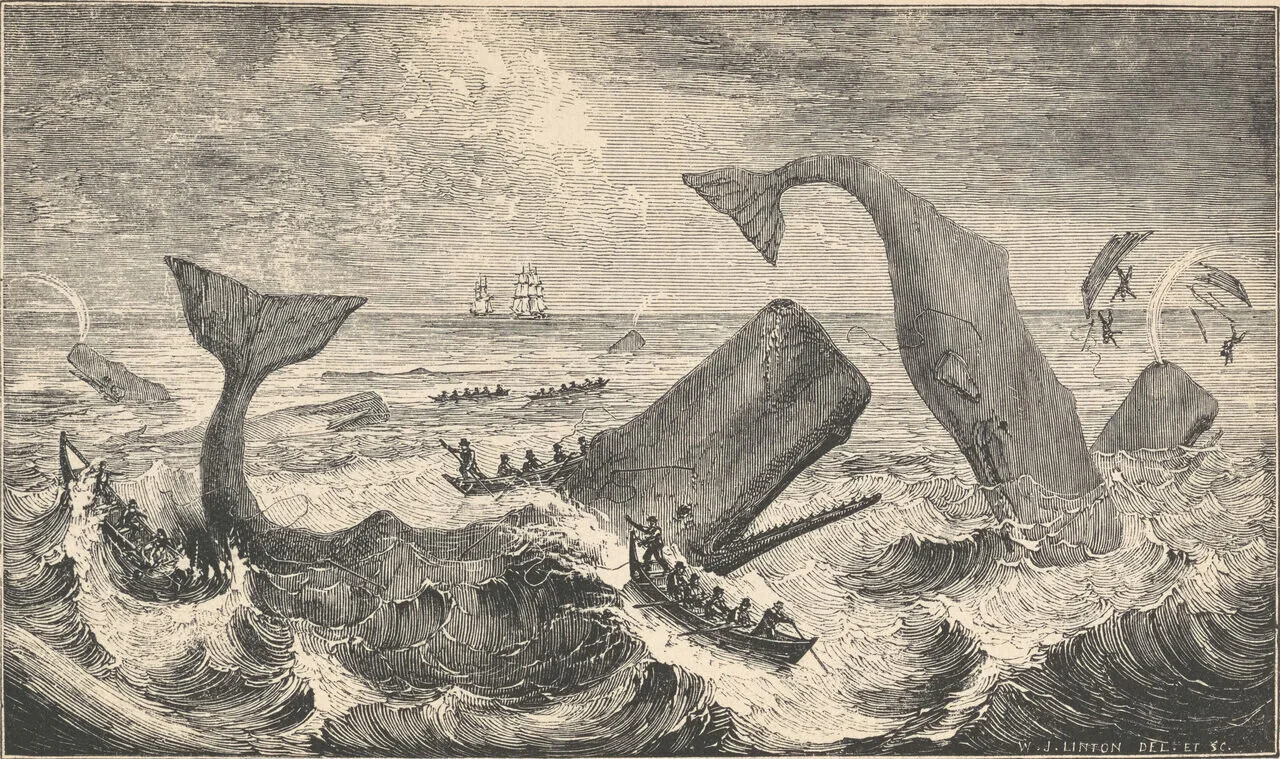

Boats attacking whales by W.J. Linton New York Public Library Digital Collection

A lone figure haunts the terrible comedy of Melville’s cetacean masterpiece Moby-Dick (1851). His name is Bulkington, and he stands at the helm in the mid-winter night of Chapter 23, silent and indomitable and ineluctably sad. He is, perhaps, more dream than man, more aspiration than soul. He is, perhaps, America, as it was when it looked first on the green, unsoiled breast of the world that would become its own rancid belly.

The six inches of Chapter 23, Melville says, “is the stoneless grave of Bulkington.” The man is neither seen nor heard the rest of the epic, though Ishmael takes the time to assure us that his fate is the same as the Pequod’s. We will not encounter him again, though we have met him once before, at the Spouter-Inn in New Bedford, where Ishmael observes a crew of mariners fresh in from the coast of Labrador:

I observed, however, that one of them held somewhat aloof, and though he seemed desirous not to spoil the hilarity of his shipmates by his own sober face, yet upon the whole he refrained from making as much noise as the rest. This man interested me at once; and since the sea-gods had ordained that he should soon become my shipmate (though but a sleeping-partner one, so far as this narrative is concerned), I will here venture upon a little description of him. He stood full six feet in height, with noble shoulders, and a chest like a coffer-dam. I have seldom seen such brawn in a man. His face was deeply brown and burnt, making his white teeth dazzling by the contrast; while in the deep shadows of his eyes floated some reminiscences that did not seem to give him much joy. His voice at once announced that he was a Southerner, and from his fine stature, I thought he must be one of those tall mountaineers from the Alleghanian Ridge in Virginia. When the revelry of his companions had mounted to its height, this man slipped away unobserved, and I saw no more of him till he became my comrade on the sea. In a few minutes, however, he was missed by his shipmates, and being, it seems, for some reason a huge favourite with them, they raised a cry of “Bulkington! Bulkington! where’s Bulkington?” and darted out of the house in pursuit of him.

Though Bulkington commands but five paragraphs, his image is embedded, potent as a mustard seed, in our reading of the tome. In his life we know only his unequivocal excellence: his brawn, his beauty, his discretion. In his death we anticipate his apotheosis, straight up from the waves which close over the whale-ship in their five thousand years’ continuum. Bulkington is forever within and without, quiet in his companions’ mirth, hulking aboard the tempestuous Pequod, bearing in his very voice the memory of societal sin. His face is brown with sun. His name is all mass. He is like a lovely city in Vermont or South Carolina, the perfect part maculate with its whole. He manifests the critical stance, the silent prophetic recognition which draws its outrageous fellows clamoring after it.

All we know of Bulkington and of the Pequod and, for that matter, of Ishmael comes to us through Ishmael. We may take Bulkington, if we wish, as one of those landmarks of the moral, melancholic Ishmaelian eye which, looking back from its survivor’s empyrean, shines the ominous ray of its memory upon the outset of its voyage.

No doubt the one we call Ishmael has earned the Dantean prophetic gaze he turns upon the inauspicious details of his exposition. Peering into the past to construct his tale, he permits his constructed eye to gaze into the future of its own construction. Who he becomes in virtue of his adventure must inform his tale, beginning with his name. We call him Ishmael as the Labrador bears of the Spouter-Inn call their comrade Bulkington, and we have no surety as to either one’s identity. What we do know is that each man sets himself up as an outsider, Bulkington by his voyaging and his slipping away, Ishmael by his name.

Through the name Ishmael gleams, as he’s described in the book of Genesis, the “wild ass of a man,” every hand against him, who descends from Abraham and from whom Muhammad will descend. To be Ishmael is to be apart, to be against, to know the wilderness. Some critical study has been devoted recently to the resonances the name would have held for Melville’s contemporary audience, largely in the context of re-evaluations of Ishmael’s race. As R.J. O’Hara points out, for instance, before 1851, the year the novel was published, 17 of the 34 men of Massachusetts named Ishmael were Black. Likewise much has been made of the fact that the Ishmael of Genesis was banished not for that wild-assery which would be his but for his status as Abraham’s son by Hagar, the Egyptian bondswoman who despised Sarah. Melville’s immediate audience was thus biblically and demographically primed to hear in the name Ishmael racial resonances which the intervening century and three quarters have dulled and film adaptations have enameled.

The question of Ishmael’s race is in some sense nonetheless moot. We cannot know his race but only the name he chooses and the resonances of that choice, which square freely with his dedication throughout the novel to Queequeg and Pip. Ishmael takes up and voices the critical stance thrummed through Bulkington’s silence. He is, like the Alleghenian, within and without.

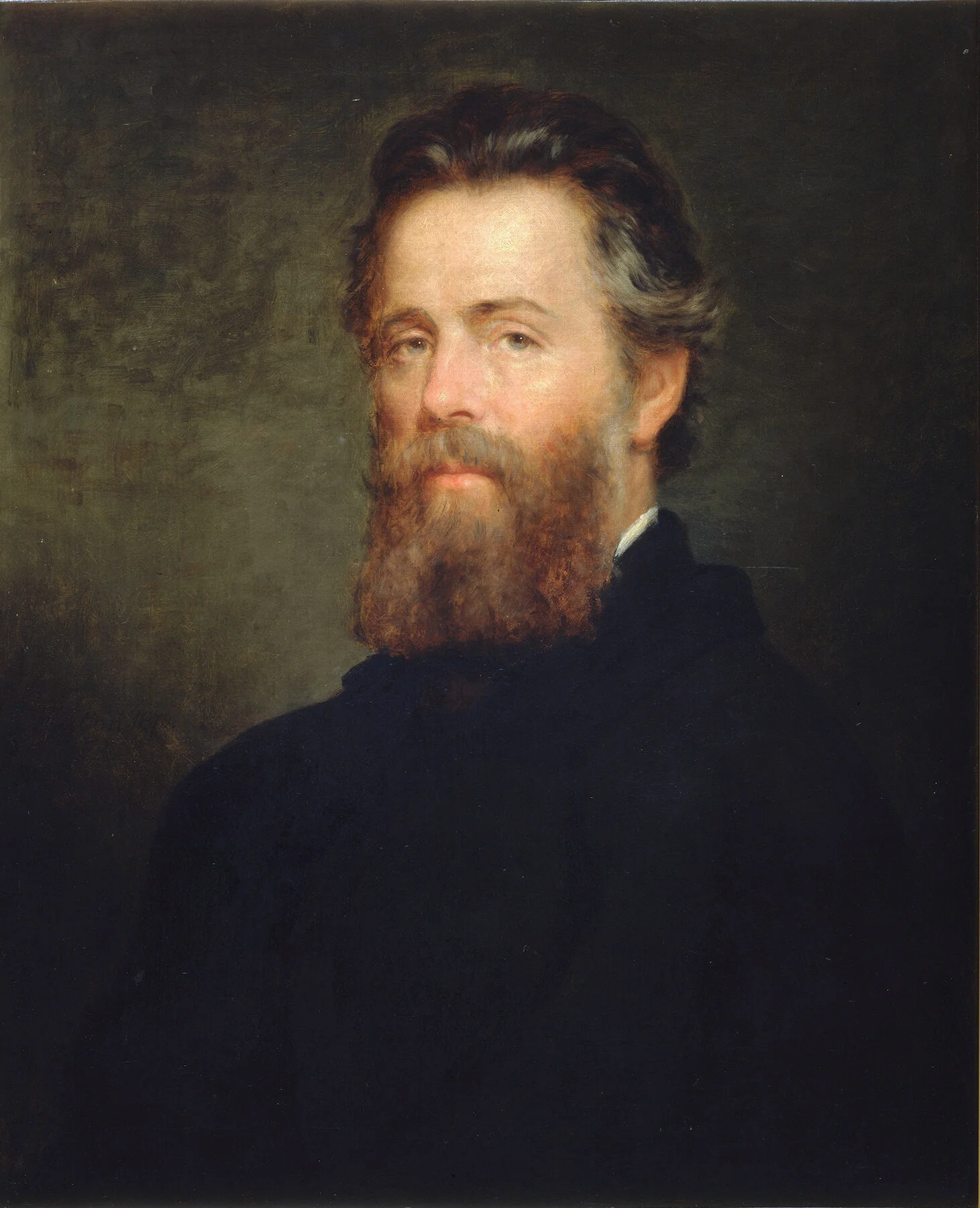

Herman Melville by Joseph O. Eaton

From the critical position Ishmael mounts his assault upon and his prayer for America. The Pequod is America, and its mad Old Covenant captain sets it against the horrifying whiteness of being, with Daggoo, Tashtego, and Queequeg casting the harpoons from the prows of the killing boats. The West African, the Gay Head native, and the South Seas chieftain’s son strive at the terminus of the whaling operation. It credits the Pequod’s crew that they show due deference to the prowess of the harpooners, yet we can’t but see in their positions the use, the usury, America has at various times and by various methods exacted of its own people and of people the world over.

We cannot know the end of America, though we know from the first unfurling of Ishmael’s prophecy that the voyage of the Pequod is doomed. Though we long, breath held, to see Starbuck work the needed regicide, we know that none on board will stand against Ahab, or will care to. Still chills course through the tale’s end, when the ship at last goes down and a sea-hawk slaloms waveward to investigate, only to be nailed to the mainmast by the flailing hammer in Tashtego’s hand: “so the bird of heaven, with archangelic shrieks, and his imperial beak thrust upwards, and his whole captive form folded in the flag of Ahab, went down with his ship, which, like Satan, would not sink to hell till she had dragged a living part of heaven along with her, and helmeted herself with it.”

America, Melville says, cannot stand up to tyrants. It will go down into the depths, its image hammered to itself by its own indigenous, denigrated citizen. Ishmael, alive by the grace of Queequeg’s casket, survives alone to tell the tale, and in the telling he identifies with the slave, with the native, with the cannibal, with the boy from Alabama driven mad by the water of the world where he was left in the wake of the whale.

In a book of mad prophets, it is only madness which can touch the mad captain. Neither reasonable Starbuck, nor piping Stubb, nor pugnacious Flask can enter the bosom of Ahab in the manner of Pip. The mad captain and the boy made mad in the megalomaniac quest together soar, like souls in a Platonic myth, at the limit of being. To reach us, rounding the world in pursuit of whatever lies behind the mask of phenomena, Ishmael gives us himself, borne home by the grief-stricken Rachel, and a tale of our own insanity. He is throughout the telling a friend of all those who speak the Ahabian mad-tongue. He is present to Pip’s night of the soul and to Fleece’s sermon to the sharks, that ravenous America the cook bids fill its belly and die. He sees in Queequeg George Washington cannibalistically defined. His tale is rooted in the innermost drama of the voyage, where lives what is most exterior to our common life.

All throughout, Bulkington is silent. He is doomed, and he knows he is doomed. We hear his doom and his knowledge in Ishmael’s report of his voice. Ishmael does not abandon him to his own silence, though. Ishmael rather gives voice to that aspiration which has resigned its voice in view of the vandalism of its tongue.

Daniel Fitzpatrick is the author of the novel Only the Lover Sings. His new translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, illustrated by sculptor Timothy Schmalz, was published this year in celebration of the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death.