Power Made Perfect in Weakness

“I believe; help my unbelief!”

These words from the Gospel of Mark speak to the universal struggle with faith and the tenuous balance between belief and doubt. They also echo in Graham Greene’s 1940 novel, The Power and the Glory. Set during the anti-clerical regime of 1930s Mexico, the novel tells the story of the last priest, a sinner, a “Whisky Priest” but the last one able to make God present in flesh to the people.

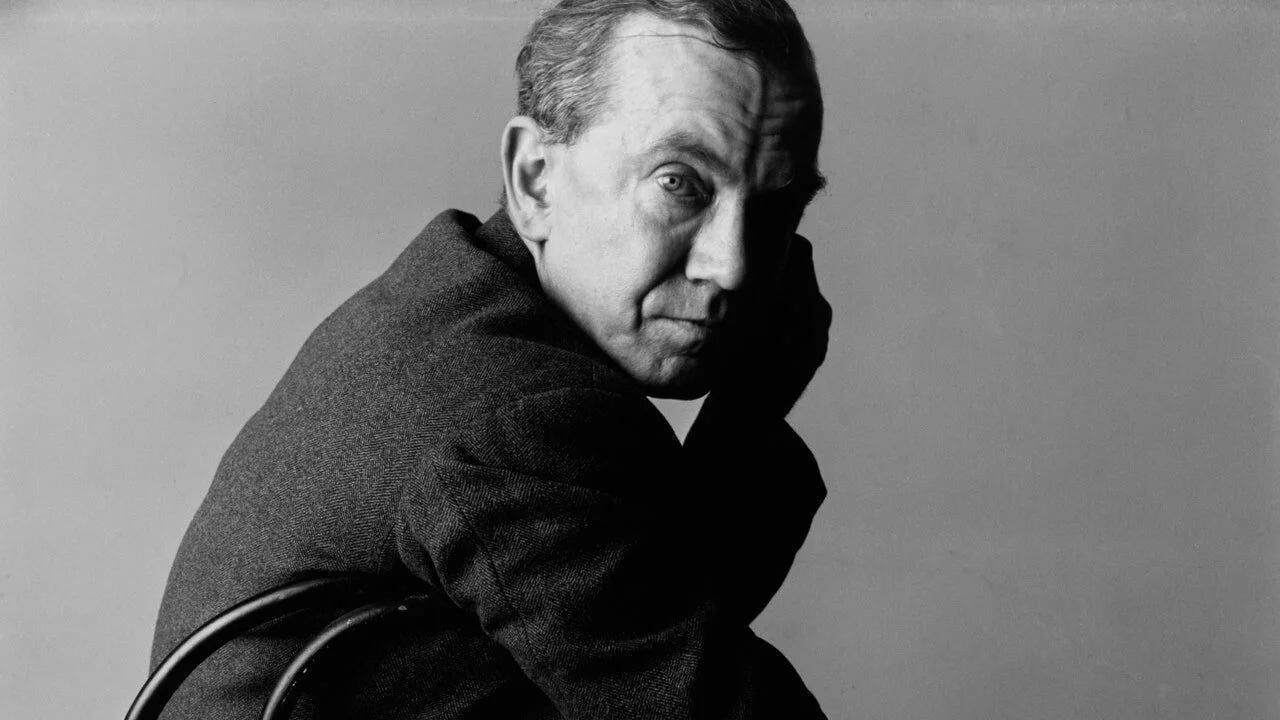

Originally an agnostic, Greene began exploring faith after graduating from Oxford. His spiritual curiosity was stirred after the writer Vivien Dayrell-Browning wrote him a letter correcting his misinformed theology in a film review he published in the Nottingham Journal. He began corresponding with her and their conversations led to his conversion to Catholicism in 1926 and their marriage in 1927. Yet it was doubt that sustained Greene’s faith. Calling himself a “Catholic agnostic,” Greene took the name Thomas, after the doubting apostle, at his confirmation. “If I were ever to be convinced in even the remote possibility of a supreme, omnipotent and omniscient power,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I realized that nothing afterwards could seem impossible.”

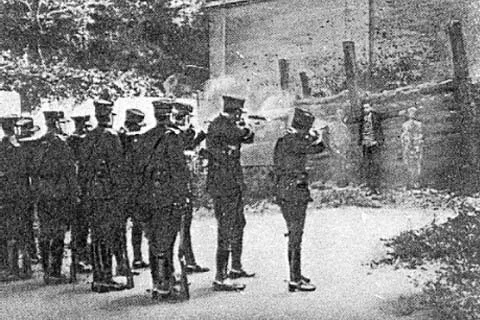

Greene went to Mexico to research the persecution of the Catholic Church during the Cristero Rebellion and saw firsthand the suppression of the Catholic Church by the Marxist government. Priests were not allowed to say Mass or administer sacraments. They were forced into marriage or hunted and shot. Greene heard of a priest who lived for ten years in the jungles of Chiapas, coming out only at night to administer the sacraments. Witnessing this oppression and attending Mass in secret, Greene concluded that Catholicism was more real under persecution. To preserve their faith, these believers had to risk death. This faith became more real, more true than what they had practiced before, than what Greene had practiced before.

Like Greene, the Whisky Priest struggles with faith. Among sinners, he is foremost. He is coined the Whisky Priest by Greene because he drinks, often. Each time he evades capture by the anti-clerical Lieutenant, he tries to find a drink. “A little drink will work wonders in a cowardly man. With a little brandy, why, I’d defy the devil,” he says. Alcohol is his liquid courage. He drinks because he’s afraid.

His sins accumulate. His fear also leads him to find comfort in the bed of a woman, resulting in a child. There was “no love in her conception,” he reflects, “Just fear and despair and half a bottle of Brandy and the sense of loneliness had driven him to an act which horrified him.” Once, he drunkenly baptizes a boy with the name Brigitta, his own daughter’s name.

Though he is a sinner, he also risks his life to make God present to those who come to him. A girl hiding him from the anti-Catholic government suggests he renounce his faith. He replies, “It is impossible. There’s no way. I’m a priest. It’s out of my power.” She understands; it’s “like a birthmark.” The gift of the Holy Spirit, sealed upon him at baptism, is like a birthmark, a mark that stays with him, regardless of whether he wants it or not.

Another priest in the novel, Padre José, also understands his vocation as a birthmark. A former priest, he chose marriage over the firing squad. Padre José is “mocked and taunted between the sheets” of his marriage bed. Marriage does not fulfill him. This was not the life he had chosen or the life that chose him. He had a gift “which nobody could take away . . . the power he still had of turning the wafer into the flesh and blood of God.” By choosing marriage, his life was “a sacrilege” and “worthy of damnation. . . . wherever he went, whatever he did, he defiled God.”

And us too? Our birthmark as Christians is the seal of the Holy Spirit St. Paul speaks of in Ephesians 1:13: “when you had heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and had believed in him, [you] were marked with the seal of the promised Holy Spirit.” It is this seal, this mark, that pulls us back to faith when we fall astray. When we choose a different life.

Perhaps paradoxically, it is the Whisky Priest—a Gollum-like character who sucks “desperately at the bottle,” steals food from a mongrel dog and a sugar lump from a child’s corpse—whom God uses to extend the sacramental life of the church. His sins accumulate and consume him. As it is written in Romans 7:18-20, he does not do what he wants to do, but does the very thing he hates.

He disgusts himself: “you see how unworthy I am” he says. These words remind us of those we say in Mass: “Lord, I am not worthy . . . but only say the words and my soul shall be healed.” Do we forget that in our weakness, Christ is strong? Do we imagine a more “worthy” character?

As a young priest, the Whisky Priest had believed so strongly and been “simply filled with an overwhelming sense of God.” His hands trembled when he elevated the Host. Then, he was not like “St. Thomas who needed to put his hands in the wounds in order to believe.”

The Whisky Priest despises what he has become, how he represents God and the Church to a generation who may never see another priest. He wants to protect God’s reputation from himself. “Loving God isn’t any different from loving a man—or a child,” the Whisky Priest says, “It’s wanting to be with Him, to be near Him . . . It’s wanting to protect Him from yourself.”

If the Whisky Priest is captured, the church is one step closer to extinction. Yet he wants to be caught. He is tired of running. At the same time, he fears being caught. Back in his village, the Lieutenant catches up with him. “Was this the end at last?” he wondered. “Somewhere fear waited to spring at him,” but “he wasn’t afraid yet.” It is as if a calm comes over him when he senses the end is near.

When in prison, the Whisky Priest wants to give himself up. He wants to bring an end to all this running. He tells the other prisoners that he is a priest, half hoping they will reveal his identity. Again, that peace comes over him, “it was like the end; there was no need to hope any longer. The ten years hunt was over at last. There was silence all round him.” He realizes it is possible to find peace “when you knew for certain that the time was short.” Peace comes when he knows the next life is near.

Graham Greene

Marked by the Spirit, the Whisky Priest is mystically connected to the believers around him. Although he is exhausted to the point of tears, he listens to their confessions—“Oh let them come. Let them all come,” he says. Even though he cannot save himself, he wants to save them. Although he finds himself unworthy, “wasn’t it his duty to stay?” For his own daughter, he prays, “give me any kind of death—without contrition, in a state of sin—only save this child.” Even the mestizo, who wants to turn him in, he must engage with. The Whiskey Priest takes responsibility for the souls of those whom he encounters.

Even toward his end, when the mestizo is obviously leading him into a trap, the Whiskey Priest goes willingly to hear the last confession of a dying man. It is a trap. He is led straight to the Lieutenant.

The Lieutenant asks why the priest continued. At first, it was apathy. He didn’t think it would get as bad as it did, and then, when he realized he was the last priest, it became a source of pride. “Pride because I stayed. I wasn’t any use, but I stayed.” He says he should have drank even more so he wouldn’t have been so afraid. He dies full of disappointment that he is coming to God “empty-handed” and that he could have been a saint if only he had “a little self-restraint” and “courage.”

But isn’t this the posture of a saint? A saint thinks of himself or herself as weak. Christ says that His “power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor 12:9). Christ’s grace is sufficient.

Looking back through the novel, the reader notices the Priest’s apathy. He wants to get caught. He doesn’t want to serve. Yet God pursues him, bringing him to people who need his gift and his power—repeatedly saving him from capture and death. Through this relentless pursuit, God reminds the Whiskey Priest that he belongs to Him. Marked by the Spirit with that indelible birthmark, as the Priest wanders, he wanders towards God instead of away. Perhaps Graham too felt this relentless pursuit as an agnostic Catholic, felt the pull of a God who will not let you go.

The execution of Miguel Pro

Do we dismiss the quiet, less dramatic nudging of the Spirit that we are marked by Him? Or must we risk death for faith to seem more real to us? Have we too become apathetic? Has faith become routine in a culture without oppression and persecution? Or have we become so apathetic that we have forgotten the power of sacraments to transcend the material world? Settling for Mass through the glow of a television or computer screen. Will we tremble once again as the priest uplifts the host?

I believe; help my unbelief!

Shemaiah Gonzalez is a freelance writer who thrives in moments where storytelling, art, literature, and faith collide.