Su Xuelin’s Catholic Vision of Modern China

The May Fourth Era, occurring in the 1920s right after the fall of China’s last dynasty, witnessed one of the country’s most significant literary movements of the twentieth century. In the past thirty years, scholars of modern Chinese literature have reshaped their understanding of writings from this period. This is because of works such as Su Xuelin’s 1929 Catholic novel Thorny Heart, which provides a fascinating example of a pro-religious outlook from this period and problematizes the once-held view among Asian Studies scholars that intellectuals in this era were monolithically against religion.

The May Fourth Era’s name refers to the eponymous 1919 student protest in Beijing against the decision by Chinese representatives at the Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) to concede economic and territorial rights over China’s northeastern Shandong province to Japan. Over the next decade, this protest inspired Chinese novelists, poets, journalists, teachers, and other intellectuals to offer varying visions of how China should strengthen itself. Debates at the time focused on the traits Chinese individuals should cultivate to enable China’s transformation into a powerful nation. C.T. Hsia, who in 1961 published the first English-language monograph on the period, characterized May Fourth Era intellectuals as advocating a turn away from traditional Chinese society, which they considered inferior and backwards, in favor of science, rationalism, and scientific positivism. He further argued that the movement was unconcerned with religion, stating that literature produced during the period lacked spiritual depth. This characterization of the era persisted in academic studies of twentieth-century Chinese literature for over thirty years.

However, more recent scholarship in the field has chipped away at Hsia’s representation of May Fourth intellectuals as rationalistic unbelievers to demonstrate that their ideas about what characteristics individuals should cultivate to give rise to a stronger Chinese society were many and varied. Su Xuelin’s novel Thorny Heart (for which there is yet no English translation—all translations from the novel are my own) is one example of such a work that challenges Hsia’s narrative of the May Fourth Era. The novel’s protagonist, Xingqiu, a Chinese student studying abroad in France, comes to believe that the selflessness and compassion she observes in French Catholics would be more beneficial to China than the pursuit of material wealth and success for which she feels May Fourth intellectuals advocate. Her conversion to Catholicism is a radical one for a self-identified May Fourth intellectual. Religion was dismissed by certain strands of May Fourth Era thought as unscientific and thus counter-productive to the goal of modernizing China.

In the novel, Xingqiu decides to study art abroad in France after high school, believing that becoming more cosmopolitan and educated will help her contribute to the strengthening of China as a nation. Once there, Xingqiu spends much of the novel torn between her professional goals and her desire to honor her mother’s wishes for her. Xingqiu’s mother, an uneducated peasant woman, has devoted her life to raising her children and homemaking. She initially approves of Xingqiu’s plans because she herself had similar ambitions, but was unable to pursue her education because of the demands her society placed on her as a woman and mother. However, she eventually changes her mind, writing in letters to her daughter that she misses her terribly and would like her to return home to enter into an arranged marriage with an engineer named Shujian. Although she wants to honor her mother, Xingqiu keenly feels the cognitive dissonance of claiming to be a May Fourth intellectual, a liberated woman, yet entering into arranged marriage instead of pursuing love of her choosing. Eventually it is Catholicism, rather than May Fourth ideology, that both helps Xingqiu resolve this personal conflict and provides her with insight into how China can best become a strong nation.

At first, she is uncomfortable with Catholicism, which is not only a religion, and thus already suspicious to her, but a foreign one at that. However, Xingqiu’s suspicion of Catholicism gradually diminishes once she begins to notice that the Catholics she has met in France are the kindest and most compassionate people she has ever known. She compares her Catholic friends to the May Fourth intellectuals she used to admire and increasingly finds May Fourth ideology wanting. France is a strong nation, she feels, because of the religious fervor of its people, which drives them to be passionate about supporting causes and helping others. She finds the May Fourth Movement, on the other hand, to be driven by selfishness, and exclaims in her diary, “to save China and to promote science are as a matter of course urgent tasks, but it is first necessary to strive for the transformation of the spirit. To strive for the transformation of the spirit, it is first necessary to break through the traditional selfish outlook and attend to moral life.” Xingqiu means that the Chinese should strive to emulate the selflessness and compassion that she has come to see as hallmarks of French Catholic life.

Although Xingqiu spends much of the novel trying to persuade herself that it is possible to cultivate selflessness and compassion without being religious, she eventually converts and persuades her mother to do so as well. After her conversion, she returns to China and accepts the arranged marriage to Shujian. Adopting a Catholic worldview enables Xingqiu to accept her mother’s plan for her life and reconciles her fundamental values with her desire to honor her mother’s wishes.

Students of Beijing Normal University returned to campus on May 7th, 1918. -Wiki Commons

May Fourth ideology as Xingqiu understands it does not provide her with a framework for valuing her mother’s contributions to her life, which are neither intellectual, nor individualistic, nor patriotic, nor cosmopolitan. She has been taught to understand that anything that smacks of social determinism is oppressive. The Veneration of Mary in Catholicism, on the other hand, presents Xingqiu with an alternative view of motherhood, one which glorifies the work and sacrifices of mothers rather than seeing them as victims of oppressive traditional Chinese customs, such as arranged marriages and traditional gender roles. In France, Xingqiu becomes fascinated with the many statues of Mary at her school and in other places she frequents. When she and her mother convert to Catholicism, they also both take the confirmation name Maria. Through her veneration of Mary, Xingqiu comes to appreciate the sacrifices her mother made for her. For example, when her mother becomes sick, she prays to the Virgin Mary for her intercession. “. . . There is nothing you do not know,” she prays, “so you need no introduction to my mother’s life. That kind-hearted and pitiable woman’s illness has been brought about entirely because of her exertions for her sons and daughters. You, Holy Mother, you have also been a mother; you deeply understand a mother’s love.” She then goes on to describe the thorns that Mary must have felt in her heart as she watched each nail being driven into her son Jesus during his crucifixion, and says that her mother’s heart is equally wounded. In other words, she is acknowledging that both Mary and her mother know how much mothers suffer, and how many thorns they have in their hearts.

By the end of the novel, Catholicism allows her to see what May Fourth ideology would not: that no request of her mother’s would ever come close to repaying her mother for her labors of love. Further, Xingqiu learns through her conversion to respect the value of her mother’s wishes for her, including the arranged marriage. Though Xingqiu initially finds Shujian boring, once they are married they eventually fall in love, and the novel ends happily. Far from being oppressive, the novel suggests, traditions can be a source of fulfillment for those who freely choose to practice them. Xingqiu’s choice to honor her mother’s wishes results in greater happiness for her than defying them ever did.

But what about the alternative interpretation of this novel: that Xingqiu is an example of a young woman who had no real choice, but rather was brainwashed into accepting a traditional role for women through the overbearing pressure of her family? Given the celebratory tone of the novel’s ending and Xingqiu’s own feelings of peace and contentment, along with the author Su Xuelin’s own conversion to Catholicism and willing acceptance of an arranged marriage in real life, this more pessimistic take could only result from reading against the grain of the narrative. It is nevertheless a possible reading, albeit a subversive one. Indeed, the scholar Zhange Ni points out that there was an outcry among some leftist critics after the novel’s publication that Xingqiu did not represent the ideal liberated woman. Qian Xingcun, along with others, posited that there was a scale stretching from feudal belief to utopian socialism along which Chinese women fell according to how liberated they were. He argued that Xingqiu belonged at the feudal end of this spectrum. Though she had achieved the basic understanding that Chinese feudal society was oppressive, she was still influenced by feudal powers. In the opinion of such leftist critics, a protagonist like this could only have been written by a woman who was herself secluded in her “ivory tower” and removed from China’s ongoing social revolution.

Still, according to Ni the novel was a commercial success. It was printed a total of eight times due to demand, right up to the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. She names two reasons for the novel’s popularity: first, that “the themes of the woman question and romantic love, both crucial to the formation of the modern nation-state, or to the imagination of the revived national community, captured the enthusiasm of an entire generation of writers and readers.” In other words, no matter how Su portrayed the love lives of modern women, this was a popular theme among educated Chinese at the time and thus was bound to catch her audience’s attention. Second, Ni points out that some Chinese Catholics at the time, “who felt marginalized in their own native culture,” also celebrated the novel’s narrative of Catholic conversion. Both the novel’s representation of modern womanhood and the varied responses to the novel after it was published demonstrate the diversity of viewpoints that existed in the 1920s about how Chinese society should modernize.

Thorny Heart is not without flaws. The novel, for example, pits the pursuit of individual professional goals against that of deepening relationships with loved ones through serving and venerating them, as though these are two mutually exclusive ways of being in the world. One could envision a way of life that encompasses in some part the pursuit of professional goals without sacrificing the daily practice of selflessness and compassion. Still, Su’s novel is significant for the vision it offers of a Catholic future for China, during a time when many short stories and essays advocated against religion.

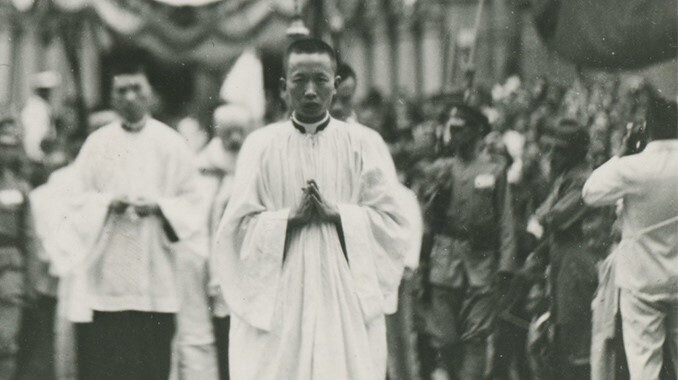

Catholic procession in Shanghai, 1950s. (Société des Auxiliaires des Missions [SAM] Collection, Whitworth University Digital Commons)

Su’s work is ultimately just one novel, and is unusual for the period, though not singular, in its positive portrayal of religious conversion. Yet Su is only one example of the many May Fourth Era intellectuals who incorporated practices and ideas belonging to older periods of history, both inside and outside of China, into their plans and ideas for a renewed China. For example, essayists Chen Duxiu and Zhou Zuoren admired the Christian promotion of fraternity and compassion. According to Asian Studies scholar Susan Daruvala, Zhou Zuoren also continued to employ traditional aesthetic categories in his works, though the May Fourth Era movement called for new forms of writing. It is now widely accepted that the May Fourth Era was not the radical break from “tradition” that its participants at the time and C.T. Hsia after them characterized it as. Rather, terms such as “tradition” and “modernity” were often relative, since May Fourth Era intellectuals strategically applied them to push for certain agendas at the expense of others, regardless of whether those agendas had roots in earlier periods of history or not. If anything, then, Su’s novel is a reminder of the freedom with which different communities decided what could be counted as “modern” and what as “traditional.”

Gina Elia is an adjunct professor of the Humanities at Broward College and a Mandarin Chinese teacher at an independent K-12 school. She holds a PhD in 20th century Chinese literature from the University of Pennsylvania, and her dissertation explored the purpose of religion in the literature of Su Xuelin and other May Fourth authors.