On the Myth of a Singular Science

Until the emergence of Digital, Medical, and Public Humanities, the Humanities proper strode alone, unaccompanied by and resistant to the parochialism of particularizing detail. Not so with the sciences, and less still with Science as a whole: these were and remain qualified by modifiers positioning them with respect to each other and to an elusive ideal. They are variously “applied,” “big,” “dismal,” “domestic,” “experimental,” “life,” “material,” “medical,” “natural,” “physical,” “political,” “popular,” “pseudo,” “rocket,” “social,” “speculative,” and ultimately, “hard.” This last descriptor has drifted in meaning from an early association with political economy and a toxic hardheartedness in the mid-nineteenth century to a plainspoken emphasis on conceptual complexity and difficulty, often with some gesture to the relative inflexibility and durability of foundational precepts and methods.

Some of these adjectives appear designed to draw a dubious domain into the force field of Science, much as the supplements “digital,” “medical,” and “public” do in the Humanities. Other descriptors, more numerous, bundle together disciplines with common practices, or objects of scrutiny, as if to insist on some form of sharing free from the threats of redundancy or of strained resources. For example, “Big Science” and the soft target of “pseudo-science” suggest public and state-sponsored monitoring of a splendid disciplinary epicenter and its contemptible hinterland. "Rocket science," no longer the exclusive preserve of federal agencies, remains a byword for oversized undertakings of extraordinary difficulty.

The variety, flexibility, and impact of these and other terms typify the West's steady engagement with Science, and the difficulty in identifying its essence. Civilization and the Culture of Science, 1795-1935, the fourth and final volume in Stephen Gaukroger's series Science and the Shaping of Modernity, is devoted to the reasons a notional Science, or on occasion individual sciences, seemed to offer a template for cognition in general, for ethical behavior, and for political organization. Gaukroger is particularly interested in exposing the insubstantial reasons for assuming that some meaningful theoretical construct or set of practices called “Science” underpins all the sciences and that intellectual energy flows irreversibly from this pure source to the low precincts of technology and popular sciences.

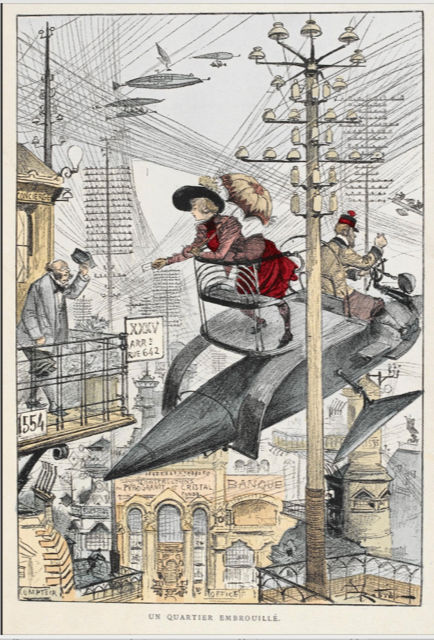

La Vie Electrique by Albert Robida

The point of tracking these tenacious notions, propagated by scientists and non-scientists alike, is less to expose their frailty than to identify the important cultural work that such impressions performed in the making of modernity. While Gaukroger describes the sciences as unruly, modular, and pluralistic, as much less securely positioned with respect either to popularization or to technology than a trickle-down model would suggest, and as offering less of a rarified lingua franca for elite practitioners than a series of autonomous idiolects largely resistant to translation, his focus is on how and why Science in the West could have seemed otherwise.

The arrangement of the argument is by discipline and roughly chronological. Gaukroger first examines the crucial terms in the ambit of “civilization” in the aftermath of the Enlightenment. He then proceeds to the emergence and careful nurturing of the notion of unity in Science, the growth of disciplines variously termed “scientific,” and the impact of activity in domains marked out as “applied” or “popular” science. Finally he turns to the question of Science as a reagent of sorts in an ongoing, and not wholly successful, civilizing process in the early twentieth century.

Among the many helpful features of the initial chapters is the attention that Gaukroger devotes both to Enlightenment thinkers' troubled assessment of non-Western contexts, particularly that of China. China’s greater antiquity and impressive civilization were routinely attributed to a scientific culture stunted by despotism, and to intra-European distinctions between Kultur, Zivilisation, Bildung, civilization, and culture. In this reading, the fusion of a scientific culture with the idea of civilization and the load-bearing fiction of the unity of Science both drew on the emergence of standardized metrics and on the idea of stadial social development, where certain technologies, political regimes, and geographical features could act as accelerants or obstacles. The Positivist ranking of sciences according to their real or imagined capacity to offer explanations ready for redeployment elsewhere, and the strategic, piecemeal translation of specific Lamarckian and Darwinian mechanisms of evolution into accounts of various phases of societal development both furthered the enterprise of a unified Science underwritten by an emergent common idiom. Here, too, Gaukroger's interest in the selective adoption of this form of “Darwinism” outside of the West sheds light on the inevitable fissures within this construct.

Why would physicists rush in where angelologists no longer tread? The erosion of a single religious authority brought some urgency, and a familiar template, to the idea of a unified Science. In some instances it was a question of regime change, and elsewhere an uneasy exercise in power-sharing. It is telling, as Gaukroger notes, that scientists had no umbrella term for themselves through much of the nineteenth century. In 1834 William Whewell proposed “scientist,” on analogy with the more familiar “artist.” More significantly, he added by way of supplement “sciolist, economist, and atheist,” a curious trio of protagonists who variously manage to operate despite deficiencies in knowledge, goods or funds, and faith. This obliquely signaled shortfall resurfaces in attempts to assert a functional equivalence between particular phenomena in physics, chemistry, and mechanics in terms of mathematical expression. Efforts to propose one of those three fields rather than a branch of mathematics as foundational, or to identify other quanta as the common currency of the natural world or as the unrecognized organizing principle of the sciences, especially in the early twentieth century, take on an explicitly political cast, where the elusive goal of unified Science seemed to some the index of national harmony, and to others a more utopian and universal pursuit.

The difficulty in repurposing theoretical models and experimental practices as significant and fruitful substrata for the sciences in general was addressed by Maxwell in an essay of 1856 on analogies in nature. At stake there was the original tension between the supposition that all natural phenomena, including thought itself, derived from movement, differed in complexity but not in essence, and could be conveyed by foundational laws of motion. There was also the belief that the entirely artifactual construct of analogy, codified as discipline-specific statutes, simply provided the sole means of describing the realm of matter. While it was possible, Maxwell added, that the Book of Nature advanced from an introduction outlining basic principles to instructive early chapters and finally to more recondite investigations, there would be no such progression, and no such progress, if it were a magazine of Nature, characterized by autonomous texts not dependent upon readers' cumulative knowledge.

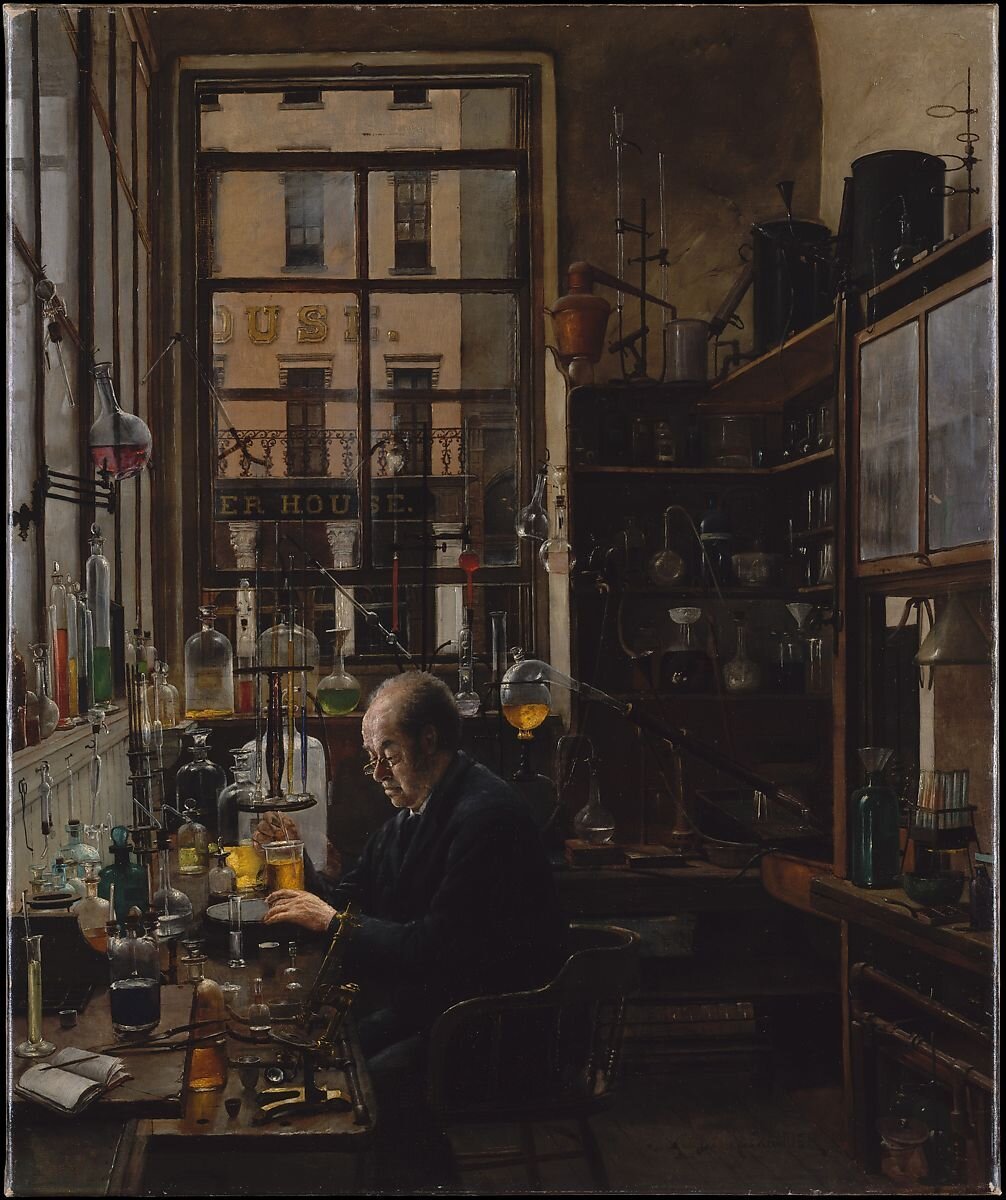

In the Laboratory by Henry Alexander

This second and rather urbane literary analogy, with its novel whiff of competition, seriality, and ephemerality, also applies to the shifting status of burgeoning individual sciences as they weighed crucial practices or particular expectations—experimentation, for instance, or picturability—as foundational, and inevitably found them wanting. Gaukroger offers lively accounts of the struggles for unity and coherence within chemistry, and across the life sciences. The latter case, animated over time by conflicts between physiologists and morphologists, an emphasis on patterns of energy exchange and the resultant irrelevance of vitalism, the sudden relevance of somnolent geology to the field with the advent of Lyell and Darwin, and the wavering distinction between variety and species, takes on special relevance as an exemplar of an unruly modular science strengthened by its explanatory pluralism. In tandem with developments in the human sciences, Darwinism rose from a specific mechanism within evolutionary biology to a broad agenda for societal change.

We return to that original “hard science,” political economy, with its emphasis on quantification, on outcome rather than intention, on the supposition of rational, purposive, well-informed actors. As always, the relevant metric was under scrutiny, as attention shifted from individuals to collectives, from types to classes, from joules to joy, or “pleasure units.” As Gaukroger shows, this sorting of disciplines, particularly in academia, was especially significant for the roles variously assigned to philosophy, and for Koyre's and Cassirer's largely incommensurable Neo-Kantian narratives within the History of Science.

Gaukroger then turns from an incisive discussion of the conflict crystallizing in the febrile environment of the Davos University Conference of 1929 over the relationship of science, culture, and civilization, helpfully described in terms of the possibility of integrating propositional and non-propositional knowledge, to two domains relevant to this question, but traditionally muted. This final and captivating section examines technology and popular science, showing the significant impact each had on “pure” Science, especially for the expectations attendant upon the professional practitioner in his guise as public figure, and for its theoretical precepts, methodological practices, and generative questions.

Zodiacal Light by Levi Walter yaggy

The material associated with mid- to late-nineteenth century Western science—children's literature, exhibitions and museums, science fiction—generally conflated science, technology, and culture. And while this orientation involved futures ranging from utopian to apocalyptic, the contemporaneous development of anthropometry, conflicting assessments intelligence and its subspecies rationality, and norms and types, under the spells of natural selection and of self-management, self-control, and self-improvement, encouraged a glimpse of the road not taken, seemingly on offer another day.

Eileen Reeves specializes in the relationship of early modern natural philosophy to literature and the visual arts.