Philosophy in Letters

This article is in a series on women who have been erased from the history of philosophy. The series is titled “Discovering the Women at the Heart of Philosophy.”

Rahel Varnhagen (1771–1833) is remembered primarily as a hostess of two of the most famous salons of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, where literary, philosophical, artistic and political greats gathered, attracted by her fabled wit and the egalitarian principles on which she ran the salons. Varnhagen’s written works, consisting mainly of several thousand letters, are important examples of the new forms of women’s writing emerging at the time, through which women developed and asserted specifically female forms of identity. These letters are increasingly gaining recognition, not just as records of a brilliant mind and the struggles of a Jewish woman of the time, but as works of literature. Recently, scholarship has also begun, belatedly, to address the significant philosophical reflections contained in these letters, especially their relationship to Enlightenment and Early German Romantic concerns regarding education, identity, authenticity, gender, sociability, and egalitarianism.

Rahel Antonie Friederike Levin was born in Berlin in 1771, the eldest child of wealthy Jewish parents. She had one sister, Rose, and three brothers, one of whom, Ludwig Robert, also became a writer. Her early friends included Dorothea and Henriette Mendelssohn, daughters of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Dorothea, better known by her married name, Dorothea Veit-Schlegel, became a central figure in Early German Romanticism.

Varnhagen complained of her lack of formal education, but she read widely and studied on her own. She read Mendelssohn, Lessing, Spinoza, Kant, Fichte, Hegel, Jacobi, Hume, Rousseau, Jean Paul, Friedrich Schlegel, Herder, Goethe, and Schiller, among others, and learned at least ten languages, including Sanskrit and Turkish.

Varnhagen’s father was domineering, and after his death in 1790 his children used the last name “Robert.” This may have been intended to mark a separation from their father, but, perhaps more significantly, it also distanced them from the more Jewish-sounding surname “Levin.” As Varnhagen wrote in 1818 (after changing her name again through marriage), “I hold this change of name to be decisively important. Thereby you certainly become another person externally.” This was particularly significant in an era when Jews were discriminated against both in law and by many of the predominantly Christian upper classes who formed most of Varnhagen’s social group.

The year her father died, Varnhagen opened her first salon, which she ran for fifteen years with her friends Henriette Herz and Sara Meyer-Grotthuis. Like her later salon, which she ran with her husband from 1819 until her death in 1833, these “teas” were well-attended by famous figures, including Hegel, Friedrich Schlegel, Schelling, Schleiermacher, Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt, Ludwig Tieck, Jean Paul, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Heinrich Heine, Bettina Brentano-von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, and Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia and his consort Pauline Wiesel. Wilhelm von Humboldt wrote of Varnhagen: “One could count almost with certainty on never leaving her without having heard and taken with you something from her that gave material for further serious, often deep consideration.” And, according to the writer and diplomat Karl Gustaf von Brinkman, “what she says is, in amusing paradox, often so trenchantly true and deep that even years later one repeats it and must consider and be astounded by it. The most brilliant and noble society assembles around her.”

In 1795–1800 and 1802–1804, Varnhagen had unhappy affairs with, respectively, Prussian diplomat Count Karl Friedrich Albrecht Finck von Finckenstein and Spanish diplomat Don Raphael d’Urquijo. She was extremely critical of marriage, which she claimed institutionalized inequality between men and women and constrained women to a way of life that could not fulfill them: “It is a false anthropology,” she wrote to her sister, “when people imagine that our spirit is different and constituted for different needs, and that we could, e.g., live wholly off our husband’s or son’s existence.” Varnhagen’s critical reflections on marriage, family, and the rights of mothers and children are valuable contributions to early nineteenth-century debates on these topics.

Despite her criticism of the institution of marriage, Varnhagen’s own marriage was a happy one. In 1808 she met Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, then a 23-year-old student, and converted to Protestantism before their wedding in 1814. It was Karl August who published three volumes of Varnhagen’s letters in the year of her death as Rahel: A Book of Remembrance for Her Friends. In addition to this and other posthumous collections of her letters, Varnhagen published around a dozen pieces in journals between 1812 and 1929, mostly literary criticism on the work of Goethe.

Although Varnhagen was born and died in Berlin, she lived in many places during her life, including Paris, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Prague, Dresden, Vienna, and Karlsruhe. In 1813 she was in Prague, caring for soldiers injured in the Napoleonic Wars and raising money for their families. Despite her contributions to the war effort, Varnhagen was not a nationalist but, rather, what one scholar has called a “cosmopolitan with a patriotic sentiment.” She wrote, for example, that “one must always love one’s country, like one’s siblings, even if you also hate and criticize them” and “that we are and are called German is an accident [. . .] every people that has learned to reason should be good, and have the freedom to be so [. . .] and every such people must grant this to and wish this for all other peoples.”

Varnhagen’s cosmopolitanism was connected with her ideas on ethics, self-development, education, and sociability (Geselligkeit). For Varnhagen, the purpose of human life is to educate oneself, cultivating one’s faculties and abilities. “Go to places where new objects, words and people touch you, refresh your blood, life, nerves and thoughts,” she wrote to her sister, and quoting the French philosopher Louis Claude de Saint-Martin: “Our future happiness will consist in experiencing something new in every moment.” Varnhagen argues that one cannot act ethically or relate well to other individuals without the freedom that is gained through having developed in accord with one’s own nature: “Our destiny is in fact nothing but our character; our character nothing but the result, in our active and passive being, of the sum and mixture of all our attributes and gifts.” Interactions between individuals, as well as between nations, should be guided by this authenticity and mutual respect for each other’s freedom to develop one’s natural capacities.

This area of Varnhagen’s thought contributes to the concept of Bildung (education, development, or cultivation) that was important at the time. Her work on this topic was influenced by Goethe (especially his Wilhelm Meister books), by Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Humankind, and by her friend Schleiermacher, who developed an ideal of an ethical community. But Varnhagen’s work on Bildung addresses the specific circumstances of women, arguing that women need to seek out opportunities to develop their aptitudes (whereas men receive these automatically through their work), and that women should receive advanced education and undertake academic research. We can also see the underpinnings of an argument for the emancipation of Jews: all nations should enjoy mutual respect and be allowed to develop to their full capacity.

Varnhagen’s letters also advance Early German Romantic accounts of friendship and sociability. Salons, where individuals from different backgrounds conversed on a broad range of subjects, embodied the Romantic ideal of “symphilosophy” (thinking together), and Varnhagen consciously replicates the dynamism and naturalness of a salon conversation in her letters. “I never want to write a speech,” she said, “But I want to write conversations, as they proceed in human beings.” The letter format is a dialogue, always addressed to someone else and emerging in interaction with them.

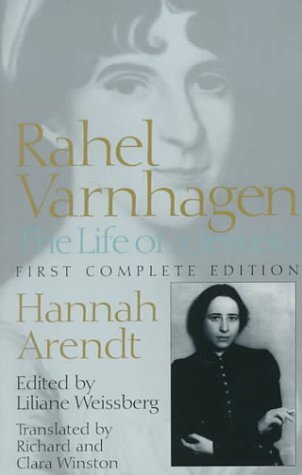

The Romantic idea of life as text—the need to create an identity for oneself through writing—is another strong focus of Varnhagen’s letters. “The human being as human being is itself a work of art,” she claimed, and “my life shall become letters.” Interpreters of Varnhagen’s work have focused on her claims about herself, which oscillate between insecurity or self-loathing and egoism (to be fair, she had much to be proud of). In particular, Varnhagen’s struggles with her identity as a Jewish woman in an anti-Semitic society have drawn considerable analysis, most prominently in Hannah Arendt’s biography Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess. Arendt, who described Varnhagen as “my closest friend, though she has been dead for some hundred years,” developed several important philosophical positions in this early work on Varnhagen, including ideas about the pariah, the parvenu (or nouveau riche), emancipation, and assimilation.

Arendt also drew attention to the methodological difficulties in interpreting Varnhagen’s writings. The texts that Karl August collected and edited for the Book of Remembrance are neither complete nor identical to Varnhagen’s original letters, and Arendt maintained that the selection obscured Varnhagen’s Jewishness, making her seem more German and aristocratic than she really was. Other scholars argue that Varnhagen left detailed instructions for the selection, arrangement, and amendment of the letters, and that Karl August was carrying out Varnhagen’s wishes. They argue that Book of Remembrance is a work of literature that Varnhagen deliberately shaped into a whole with assistance from her husband.

Whichever is the case, the task of extracting Varnhagen’s philosophical thought from her letters is daunting. In addition to the sheer volume of correspondence, Varnhagen did not write philosophy systematically or at specific points in the text. Instead, her letters are interspersed with social observations, personal news, and reflections on personal, literary, political, and scientific matters. On the other hand, many scholars note that Varnhagen’s unconventional stylistic choices are among her great strengths as a writer. Her letters transgress boundaries of genre, language, and narrative, creating a literary identity that subverts patriarchal norms for writing and forms a sustained reflection on friendship, freedom, and identity.

Anna Ezekiel is a feminist historian of philosophy and translator working on post-Kantian German thought. She has translated the writings of eight historical women philosophers for the forthcoming Oxford University Press volume Women Philosophers of the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Kristin Gjesdal and Dalia Nassar. Her translations of Karoline von Günderrode’s work are available as Poetic Fragments (SUNY Press, 2016) and Philosophical Fragments (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).