Man Is a Social Organism

Herbert Spencer

In his book The Study of Sociology, philosopher Herbert Spencer devoted a chapter to arguing for the close connection between sociology and biology. Hearkening back to the ancient analogy of the “body politic,” Spencer saw the organization of society as similar to the organization of a body—so alike that it wasn’t quite correct to call it a metaphorical relationship: “we are not here dealing with a figurative resemblance,” he wrote, “but with a fundamental parallelism...”

A growing fascination with Darwinism in the early twentieth century made Spencer’s analysis particularly compelling to many people who were rethinking what exactly the body was: it was a biological reality, and it had to be understood scientifically rather than spiritually or philosophically. The body politic too, it seemed, ought to be reimagined in light of these biological advances.

Some of the intellectuals at the forefront of this reimagining were known as eugenicists. Eugenics, the belief that success was a result of a person’s genes and that the human race could be improved through selective breeding, was a popular movement in the United States in the early twentieth century. Spencer’s theory of the “survival of the fittest” was a handy justification for this thinking, and his work became foundational for this pseudoscience.

The “Eugenics family” – 1930s emblem of the Eugenics Education Society Wellcome Library, London

Eugenicists were fascinated by Spencer’s argument that there was a direct connection between the body and the community. They sought to legitimize eugenics by grafting it onto Enlightenment and classical sources, and Spencer offered a reinterpretation of the body politic that was both modern and scientific. Eugenicists saw the body politic through the lens of their understanding of biology, and as the way they saw the body grew increasingly medicalized and clinical, so too did their view of the community.

Before the discovery of DNA, biologists considered germ plasm, a substance found in the germ cells, to be the part of the cell that contained the material of life. Eugenicists argued that this genetic material did more than lay the groundwork for a person’s personality and basic health. In their view, a person’s overall health, ability, and even morality came from his or her germ plasm. If it was good genetic material, you would be successful and healthy. If it was bad, you would be poor or disabled and more likely to become a criminal or prostitute. It was germ cells, the cells that passed this germ plasm along, that were the most important part of the body.

For eugenicists, the identity and value of the body was found in the grouping of some of the smallest biological parts. Some eugenicists argued that, rather than being a whole that comprised the cells, the body was better understood as the product of the germ cells. The most widely used college-level textbook, Applied Eugenics, defended this theory in depth. The authors, Roswell Johnson and Paul Popenoe, devoted a chapter to the germ cells and their determining role for the individual. “The body does not produce the germ-cells,” they explained, “instead, the germ-cells produce the body.”

It didn’t take long for the eugenic conception of the body to lead in some ridiculous directions. “The death of the huge agglomeration of highly specialized body-cells,” Johnson and Popenoe wrote, referring to the death of a person, “is a matter of little consequence, if the germ-plasm, with its power to reproduce not only these body-cells, but the mental traits—indeed, we may in a sense say the very soul—that inhabited them, has been passed on.” The death of a specific person mattered little, because a person was little more than a collection of advanced cells. Eugenicists reduced the person to the body and reduced the body to an organization of specialized plasm.

This was the understanding of the body that informed the way eugenicists saw the body politic. Although eugenicists were, theoretically, uncomfortable with metaphor—it seemed misleading, perhaps a little irrational—they were comfortable talking about the community as a body because it seemed so precise. The body contained structured systems, just like a civilization: cells reproduced, passing on their plasm, and took part in “exchange[s] of services,” transporting nutrients and cooperating to defeat foreign invaders. In Spencer’s view, to say that community was like an organism was to make an observation of a direct, objective connection. It was scientifically rigorous. Comparing the body politic to an organism, then, seemed closer to scientific writing than metaphor.

“The Biotypes of Giacinto Viola.” Waldemar Berardinelli, Tratado de biotipologia e patalogia consitucional (Francisco Alves: Rio de Janeiro, 1942).

It was not clear that Spencer was even comparing society to a specifically human body when he made this connection: Spencer saw the analogy as between the “individual organism and [the] social organism.” It is the biological, clinical body that he speaks of, not the lived, human body. Eugenicists followed in his footsteps and saw the community as an organism, an “agglomeration of cells.”

Metaphors inform the way we see things, and the fact that this one used scientific language did not make it any different. Seeing the community as a clinical body had certain unsettling implications, and these implications were taken by eugenicists as scientific truth.

If the tiniest parts of the body controlled how the body would turn out, it followed that eugenicists would have a vested interest in the individual people who made up society. Eugenicists were set on breeding a stronger community, so it was not in their best interest to see those they considered congenitally weak or unproductive as part of the social organism. When speaking of the poor, they compared them to parasites leeching off the body politic: the dependent, they implied, were not a part of the community but something that had latched onto it and drained it of life.

Oscar McCulloch, a reformer whose work was influential for the eugenics movement, described those who were stuck in poverty as a “parasitic growth.” He made his metaphor as scientifically accurate as possible, describing a specific parasite, with “root appendages and reproductive organs,” that fastened themselves to hermit crabs, sucking out their “juices” and living off of them. This, he argued, was exactly what the poor were like: “The pauper is one whose… self-help has given place to a parasitic life. He hangs upon the city, suckling thence his sustenance and giving nothing back.”

The parasite metaphor was effective for eliminating charity programs. From this perspective, proponents of charitable work were backward, irrational people who nurtured something that was destructive of the common good. Instead eugenicists encouraged social reformers to think of themselves as doctoring society, cutting out the “parasitic growth” for the health of the whole. A classic eugenics argument against charity was that it was kinder to let the poor die than enable them to continue making their own lives miserable through their own dependence.

As this thinking became popular, communities changed how they practiced charity. Newspapers regularly bemoaned the tax money that was being spent on the poor. Cities slashed government funding for the dependent, leaving them to rely solely on private institutions. There were mass institutionalizations of people who simply sought assistance, especially poverty-stricken people who were disabled or mentally ill.

As another reformer wrote, the survival of the poor was dependent on “the fact that they form part of a social organism and are aided in the struggle by common consent.” Eugenicists wanted to end that common consent and keep the dependent out of the social organism; the poor were setting the human race back, parasitic on the great body they were building.

If the poor were considered parasites on the body, eugenicists saw immigrants as a threat just as great but even more insidious. Eugenicists were skeptical of the metaphor of America as a “melting pot”—it was becoming increasingly common to envision the influx of immigrant groups to America as different kinds of metals that would be melted together and gain even stronger properties. One prominent eugenicist and sociologist, Henry Pratt Fairchild, set out to prove that this metaphor was neither “authentic” nor “realistic.”

In his book The Melting Pot Mistake, Fairchild built on Spencer, arguing that the community should be seen as an organism and that assimilation was closer to a “metabolic process” than a melting of metals. In his metaphor, the immigrant was a “foreign particle” that needed to be completely homogenized into the body politic. Until complete homogenization had happened, he wrote, “[the immigrant] is an extraneous factor, like undigested, and possibly indigestible, matter in the body of a living organism.”

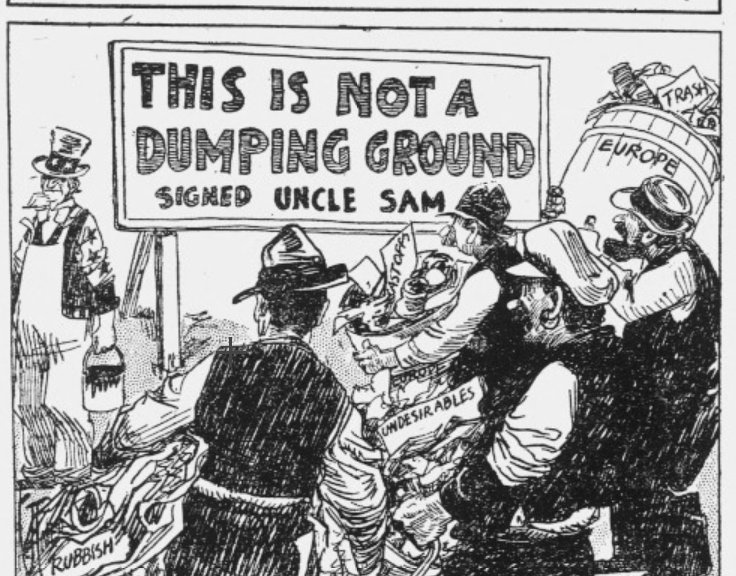

Fiery Cross. The cartoon above was published just ten days before the Johnson-Reed Act went into effect

Fairchild believed that the social organism should be careful about who it chose to accept, if it didn’t want to end up with large amounts of “indigestible” matter. It should favor those who would be easily homogenized into the dominant culture and limit anyone who was too ethnically or culturally different.

Fairchild was one of many eugenicists who rallied around the Immigration Act of 1924, a piece of legislation that limited immigration by setting a quota for each ethnic group. Immigration officials calculated how many of each group were already in the US and allowed in only two percent of that number—since their calculations were based on a census report that was already over twenty years old, this served to bring in large numbers of British and Western-European immigrants, people who were considered to be well bred and who were already in the US in large numbers, and to limit the number of Eastern-European immigrants, those with “poor” germ plasm. In addition, the Act cut out immigration from almost all Asian countries and enabled the US to turn away large numbers of Jewish refugees during the 1930s.

Our interpretation of the body politic metaphor is dependent on how we think about body—what Fairchild, McCulloch, and Johnson and Popenoe shared was a clinical understanding of the body and a belief that there was a one-to-one relationship between the clinical body and a well-run society.

Eugenicists saw the reality of the body as revealed at the cellular level. The body politic, then, was not so much a body as it was an organism, a collection of cells that were interchangeable in everything except their genetic quality. With this perspective, the body politic metaphor became an extension of scientific writing, a sort of proof that the immigrant and the dependent were biologically incompatible with the rest of society. The community that grew out of this interpretation shaped itself in strange, unsettling, and inhumane ways.

In deciding to mix metaphor with scientific writing, eugenicists were purposefully overlooking one of the fundamental strengths of the body politic metaphor: the experience of having a body is enough to understand it, no biological training necessary. By focusing on the cellular level, eugenicists were able to sidestep the body’s interdependence—as St. Paul put it, “The eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I do not need you.’” When the metaphor is informed in this way, it reveals that the parts of society are reliant on each other, that the weaker members need special care, and that each member is important because of and not in spite of the difference—in short, that society is more than an “agglomeration of cells.”