Creating a Home for Black Catholicism

Sisters of the Holy Family

Roughly 150 years ago, talks began among American Roman Catholic bishops of what plans ought to be made to accommodate African Americans in the Church. This was, of course, some three and a half centuries after the arrival of Esteban, the first African Catholic slave to set foot in North America, and not yet a century after the founding of the United States.

Throughout these 300+ years, this involuntarily transplanted group, these “Black Catholics,” had accumulated no publicly-known priests, no bishops, no protections, and certainly no solutions. Save for a peppering of Black priests beginning in 1886, this situation did not improve until the Civil Rights Movement just seventy years ago.

While this has long been referred to as a period of “second-class citizenship” within the Church, it seems more apt to term it as foreign citizenship altogether. Black Catholics in America were treated as though they simply did not belong. And, as a largely non-immigrant group in a land where they were long held as slaves, perhaps they technically did not.

These bishops, with a Vatican-sponsored plan set before them that would at the very least actualize what they so steadily implied (i.e., that Black people were so other, in station and in history, that they required an apparatus of ministry all to themselves), instead opted to distance themselves from and hoard their subjects at the same time, rejecting proposals of a national Black apostolate, vocational program, and Black seminary. Rather, as Cyprian Davis wrote, “it was determined that each bishop who had Blacks in his diocese would have the care of such a ministry. The result was that a coordinated, effective program of evangelization was never put in place.”

Fr. Cyprian Davis, OSB

The uninitiated reader might wonder why the late Fr. Cyprian Davis, OSB, would use the word “never” in the year 1988, implying that the bishops had not addressed these issues even as late as the fading twentieth century. This reader might expect that the US Church had eventually initiated a program of oversight on behalf of Black Catholics, this domestic yet foreign group, and undone centuries of slavery and segregation with a sustained attempt at lineage-based affirmative action and outreach—“reparations,” as we might call it today.

This unsuspecting inquisitor would be sorely disappointed.

Largely due to the formation of Black orders of nuns (the first in 1829, the second in 1837) some decades before the councils of Baltimore, many Black Catholics had received an education, an institutional home apart from White Catholic gazes, and a shot at overcoming the racist dictums of the day. Following the eighteenth-century American bishops’ concerted commitment to inaction on the “Black question,” the postbellum urge took hold of Black Catholics as they began to form for themselves what is today known as “Black Catholicism.”

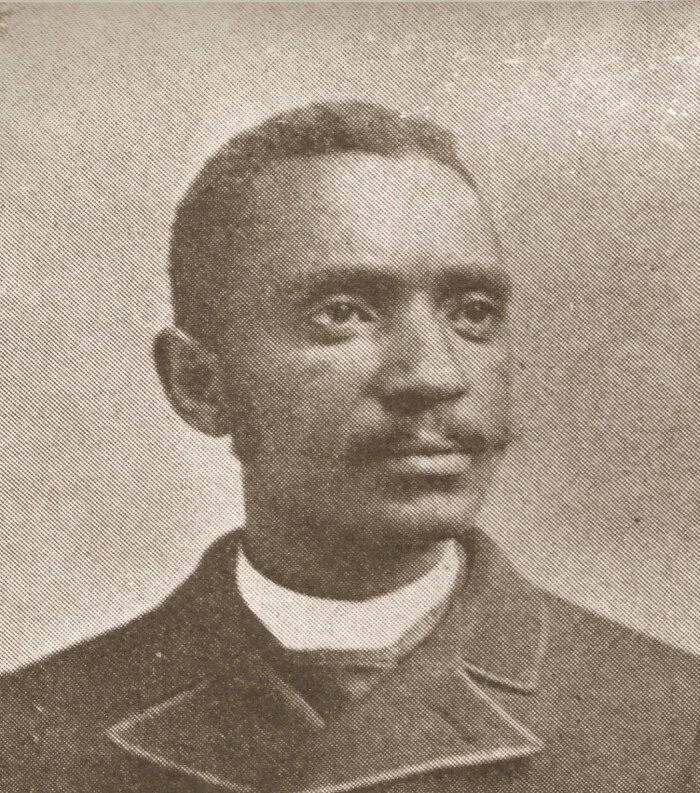

Daniel Rudd

This began with the Black Catholic Congress movement, initiated by one Daniel Rudd (1854-1933). He is largely perceived as the father of the Black Catholic Movement, a term usually reserved for the period between Vatican II and the 1990s. Rudd and his congresses would meet for five consecutive years, charting a course for what Black Catholics wished to become and for what they wished the Church to become. They began to see themselves as a unique group in nature and in situation, one which the Church readily ought to respect and hear.

Thomas Wyatt Turner (1877-1978) continued this movement in the next generation, organizing the Federated Colored Catholics as a group dedicated to social justice in the Church, specifically for its bottom-caste group. The reparations they sought were a remedy to some of the same issues seen in Black Catholicism today: the lack of Black Catholic schools, priests, and bishops, and the Church’s lack of desire to foster either.

Moreover, even if American Black Catholics could not together point to a country of expatriate origin nor a country (or particular church) welcoming enough to be called “home,” their patrimonial unity quickly became clear. In the twenty-first century, as Vatican II ripped a hole in the mirage of patrimonial uniformity within the American church, Black Catholics further emerged as an entity unto themselves. They began to form liturgies, conferences, institutes, and—most importantly—tangible streams of tradition.

Sr. Thea Bowman FSPA

What had before been a disconnected series of gasps and swipes was now a full-on movement, replete with radical thinkers, revolutionaries, and historians who deftly integrated Black Christianity with Black Catholicism both in theory and in practice. This movement, led again in many ways by Black Catholic religious sisters such as Drs. Patricia Grey (b. 1943) and Thea Bowman (1937-1990), also involved a campaign of school revitalization, as bishops across the country attempted to divest from Black communities with reckless (and literal) abandon.

Despite all this, Black Catholics failed to gain recompense. As their Eastern Catholic brethren saw increasing gains, all built upon the stony foundation of patrimony, Black Catholics—even after a 1971 private audience in the Vatican—could not manage to pry open the jaws of pontifical life to obtain for themselves the rights and returns due them. Instead of the long-owed infusion of recognition and resources one might expect after so long a period of apartheid, Black Catholics saw remarkable episcopal divestment throughout the late twentieth century (which in many ways continues).

Meanwhile, the Eastern Catholic churches in the American diaspora, which had seen vociferous repression upon their arrival in the Plenary Baltimore era (with entire Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions formed from fugitive departures), saw a recuperative ascent following Vatican II that was mercurial in comparison to Black Catholics’ ongoing struggle.

Even within the past decade, former Anglicans—whose initial departure from Catholicism was almost simultaneous with Esteban’s Floridian landing—have gained by mere request the Vatican’s approval for inculturated Catholicism free from the dismissive whims of diocesan ordinaries and the freedom not to have parishes, schools, initiatives, offices, and history erased with the stroke of an episcopal pen. That for which Black Catholics begged was seemingly handed to his brother without so much as a whimper.

Thomas Wyatt Turner

Interestingly, Black Catholics in the 1990s did attempt to gain an African-American rite—preceded by a notable schism of their own—but a 1994 survey conducted by the African-American Catholic Rite Committee (AACRC) of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC) proved abortive. According to the histories, the committee then disbanded and there appears to have been no movement since.

Within a matter of six years, High Church, reform-minded Black Pentecostal bishops were having groundbreaking ecumenical meetings with Pope St. John Paul II, discussions which continue to the present day (as one bishop had a private audience with Pope Francis just last year). Amazingly, after Black Catholics became more “Black” (and caught hell for it), Black Pentecostals immediately became markedly more Catholic.

Indeed, the very same cogs that turned not even a decade ago to form an Ordinariate for Europe’s children seem to portend the same now for Africa’s. Even so, there has been no recent news of Black Catholics returning to the Vatican for substantive redress or reform.

If it is the case that Black Catholics—having themselves lived through repeated disappointments in the modern era, stacked upon the demoralizing treatment of their ancestors—are now exhausted in the fight, now seems the perfect time to find new strength and take heed of history as the Church changes all around them (and often at their expense).

Because Rome rarely moves without prodding, I see two options for Black Catholics, as there were for Eastern and Anglican Catholics before them: go elsewhere, go extinct, or go over the heads of the US hierarchy and petition the Pope, crossing the sea in search of sea change. It is not clear whether Black Catholic leaders have done so since the 1990s, but perhaps the Ordinariate age is the perfect time to try, try again.

Cardinal Archbishop Wilton Gregory

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder of Black Catholic Messenger, a priesthood applicant with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).