Strange Rites in a Spiritual Wilderness

With Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, Tara Isabella Burton has provided a spiritual sequel of sorts to both Ross Douthat’s 2012 Bad Religion and Angela Nagle’s 2017 Kill All Normies. Burton reports from the front lines of a post-Christian American internet, where, somehow simultaneously, atomization and tribalism are dialed up to 11. For youngish readers or those who spend too much time online, it is one woman’s thoughtful perspective on an already familiar world; for the uninitiated, whether by generational remove or prudent luddism, Strange Rites is both a guide book and safari to a growing spiritual wilderness. As a medium for consumption, the internet, Burton suggests, has produced countless ways for people to enjoy the institutional or communal benefits of religiosity without subscribing to a traditional theology. From cosplay to CrossFit, these are religions “of emotive intuition, of aestheticized and commodified experience, of self-creation and self-improvement and yes, selfies.”

For anyone surprised by the rapidity with which anti-racism displayed the classic sociological features of religion in recent weeks—shared dogmas and practices producing Durkheim’s “collective effervescence”—Burton’s PhD-equipped account of contemporary a/ir/religiosity is a valuable pop-academic study of secularized faith and sacralized unbelief. If, however, one is not inclined to find meaning in a la carte consumerism and boutique identity formation, the reporting can feel a bit like a Tumblr-poem Inferno, an escalating descent into online hell.

Burton writes as a charitable observer of the “final Great Awakening in which we find ourselves today.” This moment is the apotheosis of what she calls “intuitional” rather than institutional religion, a personalized and remixed spirituality with long precedent in American history:

The refractory nature of these new intuitional religions—each one, at its core, a religion of the self—risks creating an increasingly balkanized American culture: one in which our desire for personal authenticity and experiential fulfillment takes precedent over our willingness to build coherent ideological systems and functional, sustainable institutions.

Social Justice culture and Silicon Valley futurism in particular, Burton suggests, are our two potential civil religions, the most universal of the remixed intuitionalisms. They each re-enchant a godless world with a promise of future human divinity, progress bending history to a perfected society or to digital immortality. Both assume the collapse of the current order, whether by revolutionary means or cumulative entropy. Perhaps they have more in common than their adherents think. While each likely sees the other as dystopian, they might build their utopias next to each other, tomorrow’s neighbors in the wreckage of today. Obviously, recent events would suggest the prayer books of Social Justice are getting more use, and the near-universal corporate willingness to participate in its various postures and gestures confirms Burton’s link between these new religions and consumption.

Belonging is for sale; consumer capitalism may alienate us from the products of our labor, the land, or community, but we can buy replacements. What many call “woke capital” appears not so much a co-option or appropriation, but the substance of this new religiosity, as:

a growing number of brands are selling not just products but values. In so doing, they are creating moral universes, selling meaning as an implicit product and reframing capitalist consumption as a religious ritual—a repeated and intentional activity that connects the individual to divine purpose in a value-driven framework.

Opiates come in many forms now. Some, health focused, barely look like drugs, but all have mass appeal. Even those who do subscribe to an institutional theology find themselves at times a part of this new spiritual economy. Episcopalian Burton confesses that she, too, has fallen under the spell and participated in the liturgy of identity cum entertainment. She, too, has been “a fan.”

Many of these strange rites, although enabled by the internet and the eager cooperation of capital, seem fundamentally to be about sex. These “remixed” young adults, Burton observes, “see the self as an autonomous being, the self’s desires as fundamentally good, and societal and sexual repression as not just undesirable but actively evil.” Sex is the only sacrament left to them. Marriage rates continue to decline, down to 6.5 per 1,000 in 2018 according to the CDC. Fertility is down, too. The internet has “transformed kink and poly culture from relatively fringe institutions into easily accessible, easily consumable relationship options for the uninitiated.” One could say the long reach of 1967 and ’68 continues, but the nineteenth-century American religious experiments Burton points to as precedent often had a sexual element, too: “There was, for example, a remarkably strong overlap between free love and the occult.”

A lot of people owe the Christian fundamentalists in their life an apology. Judging by Strange Rites, the common early-2000s fear that the popularity of Harry Potter would promote occultism was entirely correct. “As a spiritual practice,” Burton writes, “witchcraft may be the biggest thing since yoga.” In one of the book’s earlier chapters, but surely a deeper circle of this strange abyss, Burton writes of “Snapewives.” Snapewives are what you think they might be. They are worse than you fear. They are women who believe they have a real, spiritual—and, yes, in some cases sexual—relationship with J.K. Rowling’s greasy-haired potions professor, Severus Snape. Both witch culture and sexual utopianism are “predicated on institutional opposition,” and the usual suspect, again and again, seems to be the “strictures of heterosexual marriage.”

While Social Justice culture and techno-utopianism are the most likely heirs to or (more probably) reboots/updates of neoliberal civic society, in Burton’s telling, there is another online subculture that seeks to step out entirely of this march to the future. The “new atavists instead yearn for traditionalism, authoritarianism, and established gender roles.” Whether in the guise of bodybuilders with an affinity for Peloponnesian warriors and the Germans who loved them, or taking Jordan Peterson as its avatar, this “atavism” is a mostly male recovery of what Burton calls “materialist stoicism.” Most writers would probably call these figures right-wing reactionaries, but Burton labels them atavists. It is a striking choice, for atavism suggests, in the reversion to or reemergence of ancestral traits, an evolutionary process. This is in some sense a concession to these figures, that they are—if not actually—really trying to be throwbacks. It is also perhaps an affirmation of, if not historically-necessary Progress, a naturalness to the cultural trends these “atavists” are rejecting.

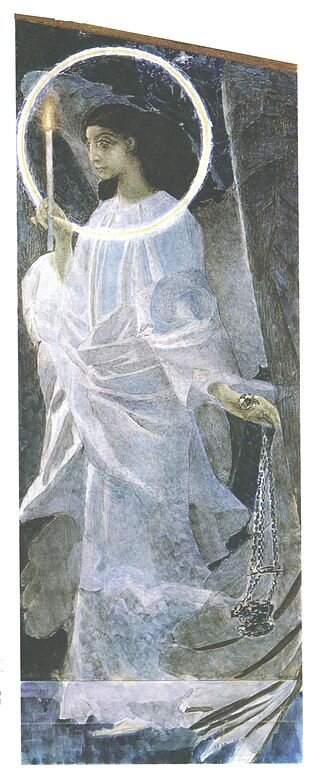

Angel with Censer and Candle by Mikhail Vrubel

Burton picks a side. These atavists are nihilists, she says. They would, of course, say the opposite; Burton is a fair reporter and gives us enough information to see this. They might argue it is the rest of society that is nihilistic, lost in the emptiness of self-definition via consumer culture and a morality cut off from its theological basis. Hearkening back to Nietzsche and the death of God, perhaps they would say that today humans must continuously question their own being and the grounds of their existence, and moreover that people might very well find nothing that counts as such a ground. They, however, seize upon nature—Darwinian selection and biological adaptation and their own bodies—as basic givens from which to carve a life. Any other foundations are more substantial acts of faith, or simply lies. Thus, Burton writes, they reject “the heart of social justice culture: that human beings are equal blank slates, and that differences between races or genders are simply imposed from without, products of a patriarchal, sexist, and racist society.” Is denial of this ontology regressive, a backtrack? Or is it the attempted recovery of something in human nature that is permanent—or as close to permanent as evolution allows?

Séance by Josef Vachal

The question of the atavists, the lingering question of Burton’s book, is the question of historicism. Can you escape your own time? Strange Rites concludes with the possibility that America is in the midst of achieving a genuine post-Christianity: “[T]he modern atavistic right, the progressive left, and the more centrist techno-utopians all can be considered pagan ideologies, which see the sacred within the world itself.” In some sense this is true. Disenchantment, secularization, modernity, make the transcendent seem very far off indeed. But post- will always mean after, and the cross leaves a long shadow. Read Strange Rites, but also read Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, by popular historian Tom Holland. Holland shows how Jesus Christ marks a genuine rupture in history, how the gospels and Christian theology radically transformed how people think about everything in the West. Building with stones from bulldozed cathedrals still leaves us in Christendom. Disenchantment, secularization, modernity, all illustrate the connection between the theological and conceptual imaginaries. Buying a beer or having brunch in a church-turned-bar is a reminder that maybe none of these three paganisms quarried their own stone. The language all of these “pagans” use, and every other Western reaction against Christianity, remains Christian. Perhaps we don’t escape our history after all.

Micah Meadowcroft is a writer and editor from the Pacific Northwest; he has written for publications such as The New Atlantis, American Affairs, and The Wall Street Journal. He holds an MA in social science from the University of Chicago, where he wrote on political theology, and a BA in history from Hillsdale College.