Genealogies in Motion: Trees of Consanguinity

We often think of genealogy using the figure of the tree, the family tree. Because a tree grows and ramifies, it seems a good figure for the extension of human lineage across time. But our modern fixation on family genealogy obscures one of the main uses of the tree figure in medieval genealogies—the determination of when people stop being related to each other as family.

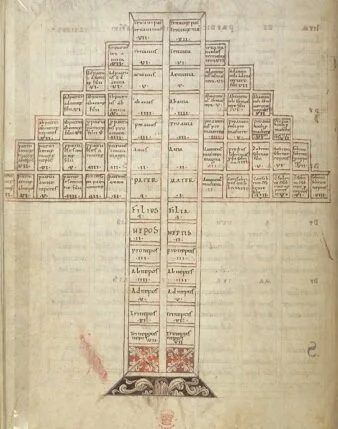

This means genealogies are always in motion, a principle expressed powerfully in medieval “trees of consanguinity”:

The tree of consanguinity models proximity and distance in familial relations. The diagram came to prominence in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies (c. 600-625 CE), where it visualizes the notion of “six degrees of separation.” The tree allowed people to determine when it was safe and lawful for relations to marry; beyond the sixth degree of separation, cousins could marry (they were no longer cousins).

The tree of consanguinity in this eleventh-century manuscript of the Etymologies looks like most other trees of consanguinity. (Here is a transcription and translation in table format.) The subject of the genealogy, the “I,” is located at the intersection of the crossed axes. Above and below are father/mother and son/daughter, with the “trunk” descending through grandson/granddaughter, etc., and ascending through grandfather/grandmother and more distant ancestors. The central two columns are flanked by relations through the father (“agnate” relations, on the left) and mother (“cognate” relations, on the right). These lateral “branches” of the diagram contain the various degrees of uncles/aunts, nieces/nephews, and cousins.

Isidore’s comments on the tree encourage readers to imagine it in motion:

While this consanguinity diminishes towards the last degree, as it subdivides through the levels of descent, and kinship ceases to exist, the law recovers it again through the bond of matrimony, and in a certain way calls it back as it slips away.

Unlike a genealogical family tree, which grows and ramifies as generations proliferate, the tree of consanguinity stays the same size and shape. At the same time, individuals and families pass into and out of relationship with each other through its structure. When a new generation is born and a new individual occupies the subject position, the branches remain the same, but the contents of the boxes change. The contents of the boxes are always in motion. Each new generation bumps the previous generation into the next row. And so each new generation also bumps one generation out of the tree entirely.

A comment in the Foigny Bible further invites readers to animate the diagram, imagining it “unroll[ing] within itself”:

This (representation) of Consanguinity gradually unrolls within itself until it goes along to the extremities, right up to the sixth degree. At this point all relationship ceases completely. Unions are allowed and thus marriage is restored.

As the diagram unrolls within itself, each new generation rises up from the trunk and pushes the occupants of the boxes up and out. First-degree relations become second-degree relations, and so on. The outermost boxes contain seventh-degree relations, the point at which “relationship ceases completely” (according to canon law prior to 1215). Each person in a seventh-degree position can therefore be imagined as the origin point of a different tree of consanguinity. Each seventh-degree relation is also the zero degree, an individual with its own tree of relational distance and proximity.

This principle is not limited to the outer fringes of the tree. In fact, each individual node of the tree is also the origin of its own tree of consanguinity. Every person is an origin in a different tree of consanguinity.

Furthermore, each individual is implicated in multiple overlapping trees of consanguinity. For example, I am a second-degree patrilineal relation to my brother’s son at the same time as I am a sixth-degree matrilineal relation to the granddaughter of my mother’s first cousin. By counting the boxes in my tree of consanguinity, I can see that I occupy 42 different nodes of significant relation (defined as six degrees or fewer) with older generations (assuming that every one of my ancestors produced both male and female offspring). This means that I occupy a position in at least 42 other trees of consanguinity—and quite possibly many more, if any ancestor had two or more male or female children.

These reflections help us to see the complexity of the “genidentities” that Timothy Barr explored on this site. In order to comprehend my own genidentity—the totality of my significant familial relationships—I would need to identify all of the trees of consanguinity in which I participate, and my position within each.

Moreover, I would have to recognize that I cannot grasp my genidentity while I am alive. My genidentity is not complete until my descendants have passed through six degrees of relation. I will potentially be implicated in 84 trees of consanguinity—and even more, if any descendent has more than one son or daughter.

If we draw an analogy between trees of consanguinity and genealogies of modernity, it suggests a number of conceptual axioms:

Proximity and distance between historical phenomena are important factors in understanding their relationships.

At some point of distance between two phenomena, relation is no longer significant. Just because we can identify a “genetic” relationship between two historical phenomena, this does not mean that the relationship is one of significant proximity.

It is also possible to pass back into significant relation at a later date.

Significant proximity will be determined by purpose and convention. Just as marriage, inheritance, and aristocratic succession depended on different rules of proximity, so also will different disciplines and methodologies—such as jurisprudence, literary history, and history of science—apply different rules of proximity, depending on their various purposes.

Genealogical relation can be configured in many ways, depending on what is taken as the origin point.

Genealogical relation depends as much on the future as it does on the past. We cannot grasp the genidentity of any present phenomenon during our lifetime.

Genealogical relation is always in motion. Because of the limitation on significant proximity, the variation of genealogical relation is not infinite, but the range of motion within even a limited tree of consanguinity entails substantial complexity.

Just how substantial is this complexity? In human genealogy, we are rarely acquainted with relatives beyond the third degree. Even with crowdsourced genealogical databases such as Ancestry.com and coordinated DNA testing, it is uncommon for an individual to be able to fill out an entire tree of consanguinity.

How much more complex are historical phenomena! To begin with, events, doctrines, genres—to name a few examples—are governed by no natural principles of individuation as are humans. Even if they were naturally individuated, historical inquiry wants to understand the relationship between disparate kinds of phenomena. We desire, for example, not only to understand the relationship between the movements of the Renaissance and the Reformation, but also between the Reformation and tragedy, or between the Battle of Lepanto and the devotion of the rosary. The genealogy of historical phenomena would seem to be intractably complex.

For this very reason, though, genealogical inquiry is important. Genealogical tools such as trees of consanguinity simultaneously display complexity and simplify it. By imposing principles of significant proximity, trees of consanguinity simplify relations for the specific purposes of marriage, inheritance, and succession. Likewise, genealogies of modernity are at their best when they both demonstrate complexity and simplify historical relations by applying principles of significant proximity for specific purposes.

In a future post, I will explore how different modes of genealogy in humanistic inquiry lend themselves either to demonstrating complexity or to simplifying that complexity. For now, I want to conclude by noting that the medieval tree of consanguinity does both. The current tendency of historical scholarship is to conclude by demonstrating complexity. These tend not to be hard-won conclusions.

The analogy between the tree of consanguinity and genealogical method in the humanities presents a challenge to historical inquiry: to represent the complexity of relations among historical phenomena while also identifying and interpreting significant proximity and the dynamics of passing into and out of significant proximity.

Ryan McDermott is the Director of the Genealogies of Modernity Project, associate professor of medieval literature and culture in the Department of English at the University of Pittsburgh, and founder and faculty director of Beatrice Institute.

Tree of Consanguinity found in a manuscript of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies