On the Ambiguity of Conversion

Edward Baring’s most recent book, Converts to the Real: Catholicism and the Making of Continental Philosophy, offers us many potential avenues for thinking about the origins of continental philosophy, beginning with the title. What does it mean to be a convert to the real? What is the “real” that we are supposedly converting to? What is Catholicism’s role in not only the making of continental philosophy but also the conversion to the real?

To begin, Baring states, “The supposition that religious ideas might slip into secular philosophy unannounced, or that purportedly ‘Christian philosophy’ might arise from the rational development of secular ideas, is crucial for my argument.” This passage introduces us to the way in which conversion takes place at the borders of two of the most radical possibilities in philosophical thought, namely, theism and atheism. For conversion, in this context, can mean a conversion toward God as well as away from Him. This is what Baring calls the “ambiguity of conversion.” While Baring gives many well-known and high-profile examples of the atheistic strand of contemporary continental philosophy (e.g. the staunchly atheistic existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre), one of the most important (albeit often overlooked) schools of thought at the origins of contemporary continental philosophy were the neo-scholastics. The neo-scholastics, whose quasi-official foundation can be traced to Pope Leo XIII’s Aeterni Patris (1879), primarily understood themselves as contributing to the revival of medieval Scholasticism. Within the bounds of a highly contentious intellectual scene, the “neo-scholastics sought a philosophical conversion of modernity, a movement from modern to medieval metaphysics—idealism to realism—which, they hoped, would be a precursor to a religious conversion back to Catholicism.” Accordingly, there are two different kinds of conversion: (a) a philosophical conversion and (b) a theological conversion.

Does the ambiguity of conversion affect both senses of conversion, that is, philosophical and theological? Baring draws attention to what we could call the double ambiguity of conversion by pointing to the peculiar neo-scholastic reception of Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology. Initially, Husserl enjoyed a positive reception in the eyes of neo-scholastic thinkers, who were among his first readers. One of the main philosophical opponents of the neo-scholastics were the idealists, who asserted that truth was mind-dependent, that is, dependent on the subject. The neo-scholastics turned to Husserlian phenomenology “to bypass the distortions of idealism and provide access to the mind-independent real.” Neo-scholastics’ initially positive reception of phenomenology was inspired by the latter’s capacity to provide a means of accessing the real. While the modern philosophers of previous centuries wanted to stress the way in which the real was dependent on the mind, Edmund Husserl’s well-known statement “To the things themselves!” provided phenomenology with the key methodological resources needed to address the real on its own terms. Thus, one could say that the merit of phenomenology, according to the neo-scholastics, rested on the ability of this new school of thought to prepare the first level of conversion to the real (i.e. the philosophical one).

St. Edith Stein

Baring discusses how in the neo-scholastic reception of phenomenology, this first level of conversion to the real was meant to lead to the second level. According to the neo-scholastics’ self-understanding of the interrelation between philosophy and theology, it was nearly impossible to convert to the real (in the philosophical sense) without feeling the demand of the second level of conversion (i.e. the theological one). Thus, the neo-scholastics placed their hope in phenomenology as the contemporary school of thought that would bridge the gap between these two levels of conversion, namely, the possibility of accessing some mind-independent reality (i.e. a philosophical conversion) as well as “help[ing] secular thinkers recognize God’s order in the world.” Or, to put it more specifically, in Baring’s own terms, “By engaging with phenomenology, then, neo-scholastics hoped they could convert modern philosophy to their ends, and overturn a process of intellectual secularization they traced to the Reformation.” Throughout their engagement with phenomenology, the neo-scholastic philosophers found reassuring signs of the former’s promise “by the unusually large number of personal religious conversions that punctuate the history of phenomenology”—such as Edith Stein, Max Scheler, and Dietrich von Hildebrand. “Phenomenology,” Baring writes, “fascinated them [Catholics] because it led to conversions in both directions: while for some, phenomenology kindled the sparks of faith, for others it snuffed them out.” As Baring notes, while there are stories of both philosophical and theological conversion in Stein, Scheler, and von Hildebrand, there were also conversions in the opposite direction, namely, Martin Heidegger, Scheler himself, among others.

The ambiguity of conversion strikes again by presenting us with two seemingly incompatible paths: “Did it [phenomenology] open up a path toward scholastic truth? Or did it provide an escape route out of Catholic orthodoxy?” However, the vertigo we experience as a result of the ambiguity of conversion provides us with an opportune moment to reflect on the way in which conversion, like faith, is not a one-way street. It is a labyrinth of different paths that sometimes leads in one direction (e.g. theism) and traces, at other moments, in other directions (e.g. atheism). While Converts to the Real traces offers an important historical reading that traces several decisive moments of the Catholic reception of phenomenology, the book’s singular force comes from its implicit claim that, as Heidegger formulated in the most precise manner in §7 of Being and Time, “We can understand phenomenology solely by seizing upon it as a possibility.” And to think of phenomenology as a possibility or as possibility itself leads one in the direction of thinking of conversion as possibility. But, to understand conversion as possibility is already to dwell within the ambiguity of conversion itself. For, as Baring emphasizes throughout the book, the possibility of conversion sets in motion the very conversion of possibility. In other words, conversion is that which possibilizes or what makes possible a different kind of relation with the real—the possibility of encountering it with a different set of eyes.

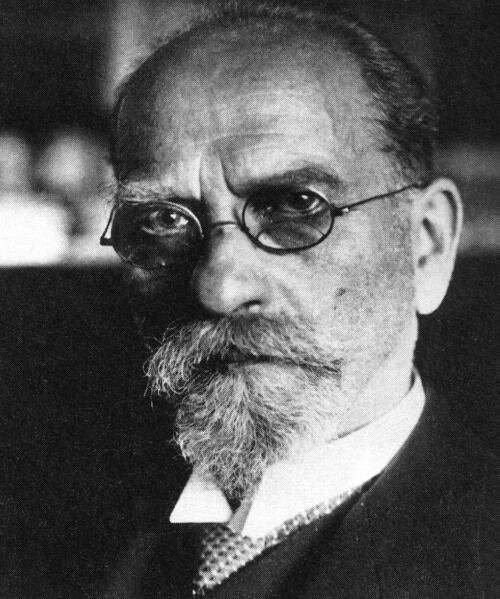

Edmund Husserl

By understanding phenomenology first and foremost as possibility, it is possible to recover its capacity for converting us to the real. Whether by way of Heidegger’s own formulation of the methodological principle of Being and Time (i.e. phenomenology allows what shows itself to be seen from itself, just as it shows itself from itself), or Husserl’s formulation of the principle of all principles in Ideas I, §24 (i.e. any intuition presented to a consciousness is a legitimate source of cognition within the limits of what presents itself), or even, in its most recent instantiation, in a thinker such as Jean-Luc Marion (i.e. in its simplest formulation, “so much reduction, so much givenness”), phenomenology finds a way of introducing us to the rich plurivocity of the real (to paraphrase Aristotle, the real is said in many ways). As any phenomenologist would acknowledge, the history of phenomenology is the history of the different ways of encountering and describing the real. And this is perhaps the crux of Converts to the Real: that one of the ways in which the real moves us—that is, one of the ways in which we encounter it—is not only by way of our conversion to the real (which, strictly speaking, would be only the first step in an infinite process of conversion) but, additionally, by letting the real convert us, by letting the real offer us the gift of its possibility by way of a self-transformation through our exposure to the real. And there is perhaps no space more adequate for this conversion of the real in both these senses than religion.

As Baring notes in the “Epilogue,” “Continental philosophy today is haunted by religion.” It is in the phenomenon of religion that the ambiguity of conversion perhaps finds its highest point. It is clear that “whether they consider religion as something that needs to be exorcised, conjured up, or—and this is where my sympathies lie—mined as an intellectual resource, philosophers across Europe have returned insistently to religious themes and questions.” Religion provides a moment of conversion—not simply theological but, as we have seen, philosophical. Religion, in whatever way it comes, gives us an opportunity for reflection such that, as Baring is able to point out throughout his book, Catholics, lapsed Catholics, former Catholics, anti-Catholics, believers, and unbelievers alike offer us different ways of approaching the truth.

At the end of the day, the moment of conversion, especially in its essential ambiguity, offers us an opportunity for converting and re-converting to the different ways in which the real is given to us. In whatever way phenomena show themselves, the real is given to us as a gift that continues giving, even to those who refuse to receive the gift. Thus, as Baring points out, “it is as if the religious reading of phenomenology is dependent upon a recessive gene: though it might skip generations of continental philosophers, its return always looms as a promise or a threat.” Phenomenology allows us to dwell with the ambiguity of conversion and to find a moment of infinite conversion following the many ways in which phenomena show themselves to us. And this is perhaps the way in which phenomenology continues, to this day, to sustain the possibility of thinking—by giving us the infinite possibility of converting to the real. For, as any careful reading will show, Converts to the Real is not simply a detailed history of the making of continental philosophy. Rather, the book’s greatest strength is that of asking us to revisit carefully the possibilities that are still latent in continental philosophy today by paying close attention to the history of its making. In the epilogue, Baring offers the following suggestion that merits further attention: religion remains one of the most persistent possibilities of contemporary continental philosophy, and it will continue to offer us different ways of thinking about the conversion to the real in its double ambiguity.

[I would like to express my gratitude to the Converts to the Real reading group at Villanova University (Terence Sweeney, Jen Wang, and Kit Apostolacus) for the discussions revolving around this book. Additionally, I would like to thank Laura Graciela Campos de González for her valuable help and input in working out these ideas.]

Humberto González Núñez is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Philosophy at Villanova University.

The Conversion of St. Paul by Parmigianino