Action Movies and the Ethics of Climate Malthusianism

Spider Man Dissolves in Avengers: Infinity War

Apart from their being expensive action blockbusters, Kingsman: Secret Service (2015, dir. Matthew Vaughn), Avengers: Infinity War (2018, dirs. Anthony and Joe Russo), and Tenet (2020, dir. Christopher Nolan) do not appear to have much in common aesthetically. Kingsman combines the hijinks and suave manners of a James Bond flick with the gritty, crass sensibility of a Guy Ritchie film. Infinity War apotheosizes the decade-long, megacorporate exercise that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe, stuffing dozens of characters and plotlines into a nearly three-hour epic. Tenet, the most cerebral of the three, has a puzzle-like structure characteristic of Nolan’s directorial style that introduces metaphysical stakes to the globe-trotting spy thriller genre—call it le Carré by way of quantum physics. Yet these movies share something important beyond their cinematic genre and hefty budgets. If we look to the villains of these three films, we find that they are speaking in unison about a common issue: human population.

Kingsman’s Richmond Valentine (Samuel L. Jackson) is a socially conscious billionaire. Wearing flat-brim baseball caps with bespoke suits, he makes climate change his philanthropic mission. One snag, though: the titular Kingsman organization—a souped-up, more exclusive MI6—discovers Valentine’s grim approach to staving off global warming. “When you get a virus, you get a fever,” Valentine explains,

That's the human body raising its core temperature to kill the virus. Planet Earth works the same way: Global warming is the fever, mankind is the virus. We're making our planet sick. A cull is our only hope. If we don't reduce our population ourselves, there's only one of two ways this can go: The host kills the virus, or the virus kills the host.

Valentine’s plan? Offer the world free SIM cards under the guise of providing phone access as a public good, only then to activate a hidden feature of the card which turns any human nearby into a raving killing machine. Let the herd thin itself out, after which those remaining—largely, the ultra-wealthy like Valentine, who he provides shelter for in a luxury Arctic bunker—can survive.

Valentine from The Kingsmen

Thanos (Josh Brolin) becomes the antagonist of Infinity War and Endgame for a similar population reduction plot, although his operates at an even greater scale: the galaxy. By gathering a series of “Infinity Stones,” Thanos gains the ability to wipe out half of interstellar existence with a snap of his fingers. His reasoning, while less specific to climate change on Earth, aligns with Valentine’s. As he tells his daughter Gamora (Zoë Saldana), “Little one, it's a simple calculus. This universe is finite; its resources, finite. If life is left unchecked, life will cease to exist. It needs correcting.” Infinity War concludes with that correction: Thanos, sporting the all-powerful “Infinity Gauntlet” encrusted with the Infinity Stones, snaps his fingers, and across space bodies begin to dissolve into flakes like dying leaves.

Thanos from Avengers: Infinity War

In Tenet, a spy known only as “the Protagonist” (John David Washington) finds himself working for a shadowy organization (the eponymous Tenet) that aims to avert “World War III,” which, in Nolan’s imagination, takes place between the future and the present. People in the future, armed with an “algorithm” that if activated would eliminate the human race, are sending this algorithm in pieces to a Russian arms dealer called Andrei Sator (Kenneth Branagh). As the Protagonist attempts to counteract the future’s “cold war” on the past, he finds out from Sator why the future seeks to eliminate the human race, in one brief but telling line: “Their oceans rose and their rivers ran dry.” Having suffered the worst consequences of climate change, humanity’s future decides that the past deserves to die for what it’s done. At least Valentine and Thanos left some people alive.

Sator from Tenet

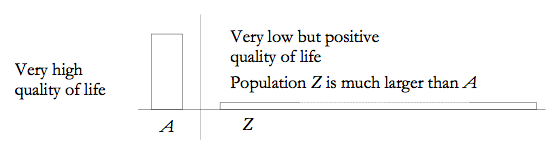

Taken together, Valentine, Thanos, and Sator’s schemes relate to a growing sub-field in philosophy, especially in America and Britain, known as population ethics. Perhaps the most famous contemporary work on population ethics is Derek Parfit’s landmark 1984 book Reasons and Persons, which introduced a thought experiment called “the Repugnant Conclusion.” At its most simple, the experiment asks us to consider two populations, as seen in the graph below:

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

For Parfit, the “Repugnant Conclusion” derives from a utilitarian understanding of these two populations. While people in population A enjoy a high quality of life, there are simply more people in population Z, even as they face a significantly lower quality of life. Taking the greatest good of the greatest number into account, one must conclude that Z is preferable to A, since a greater number of people benefit from existence even as they are worse off than population A. In short, better that many people live worse lives than fewer people live better ones. This kind of calculative thinking underlies Valentine and Thanos’ schemes, since they believe the world to have a population like Z, and through their machinations they aspire to cull the population to a size close to A.

Sator, working on behalf of the future, adopts one of the most radical views in population ethics: anti-natalism, expressed by the likes of David Benatar. On this view, it is morally wrong to bring people into the world in the first place. As Benatar puts it in his book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, “It is curious that while good people go to great lengths to spare their children from suffering, few of them seem to notice that the one (and only) guaranteed way to prevent all the suffering of their children is to not bring those children into existence in the first place.” Sator expresses this view to the Protagonist, lamenting his having brought a son into the world.

While Valentine, Thanos, and Sator manifest and weaponize the most extreme views of a contemporary field like population ethics to address an urgent present-day concern like climate change, their schemes share a common genealogy that dates back hundreds of years ago to a key figure in modern demography: Thomas Malthus. In An Essay on the Principle of Population, the eighteenth-century English economist tackled the question of the perfectibility of human society, a goal he believed was achievable given the right circumstances. Societal improvement, according to Malthus, too often finds itself in a vicious cycle where gains made in civilization—increased crop yields, the development of new technologies—result in further human proliferation, rather than an improvement to the quality of life for those already living. A dynamic wherein human progress leads to bigger populations, which then results in fewer resources being allocated on a per-person basis, is for Malthus bound to lead to poverty, famine, and war, which will ultimately chip away at the growing population. As Thanos says in Infinity War’s sequel Avengers: Endgame, this cyclical process in Malthus is “inevitable.”

One could, in theory, take Malthus’ theory descriptively rather than normatively; that is to say, his argument could be describing a state of affairs rather than deeming pernicious things like war and starvation as good (or even morally neutral) events. But as Michael Shermer notes, however one reads Malthus’ Essay, its legacy is one of politicians and public figures taking its predictions as prescriptions. Examples spanning nineteenth-century poor laws in England to twentieth-century eugenics movements in the United States illustrate a tradition of using Malthus to justify violence against human populations. By and large, the consensus is that Malthusianism is empirically questionable at best and, at worst, a fuel for social ills like colonialism and racism. Allan Chase dubbed Malthus “the founding father of scientific racism.”

And yet for all the criticism his theories have faced, Malthus finds an afterlife in the villains of three major blockbusters, seen by millions upon millions of people worldwide. What about Malthus’ account of population growth could prove so useful in scripting motivations for cinematic antagonists? Here, it seems to me, these three films invert John Milton’s famous dictum in Paradise Lost, which seeks to “justify the ways of God to men.” Kingsman, Infinity War, and Tenet stage conflicts that aim to justify humanity’s continued existence, be it to a God or to the universe more generally. (Of these three films, only Infinity War has anything resembling a divine metaphysics.) The heroes of these pictures repudiate their Malthusian adversaries, and in so doing undermine the notion that the villains’ vision of humanity is about human betterment, when in fact it is about the exertion of power over others, especially the disempowered and impoverished.

The rationale of climate change, however, adds a complication to the motivations of Valentine, Thanos, and Sator. For it is true that human activity has wrought harm on the environment that, barring drastic global action, will result in rising sea levels, increasing extreme weather events, and catastrophic population displacement. The fault of rising temperatures falls most of all upon Western countries with heavy carbon consumption, and so it is fitting that the institutions to which these films turn to save the world, such as spy agencies (Kingsman and Tenet) and quasi-military groups of superheroes (Infinity War), are also tasked with defending those countries. These organizations therefore justify the ways of specific groups of humanity, not just humanity writ large. It is easy to read these movies as reactionary. Kingsman, in particular, treats concern for climate change as ultimately murderous, in a way that the existential mood of Sator does not. But the recurrence of Malthusian motivations in the last half-decade of action cinema points towards something else: guilt.

Kingsman, Endgame, and Tenet’s villains evince the hubris of the very powerful, convinced as they are that they can fix the problems to which they contributed, using methods that helped cause those problems in the first instance. But it is guilt that makes these villains interesting, far more interesting than another iteration of a dominant man drunk on his own power. Western audiences watching these movies benefit from the same systems that gave these wealthy men power, and it is those same systems that are currently forestalling any potential mass movement for climate change. Right before their very eyes, these audiences hear two competing claims: Yes, humanity is worth fighting for, and Humankind has gone too far, and balance must be restored. Certainly, we must reject such simplistic Malthusian framing. Action films, even the best ones, are liable to recycle old archetypes of hero and villain. But as climate change continues to alter the landscape of Earth right now, and as people around the world fight for a greener future, I expect that this is not the last we will be hearing from the Valentines, Thanoses, and Sators of the world. When they appear, we must remember the tradition from which they are drawing and insist on better ways of thinking and acting.

Brice Ezell is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Texas at Austin, where he studies modern and contemporary theatre. His scholarly work can be found in Modern Drama and The Eugene O'Neill Review, and his cultural criticism has been published at PopMatters, Consequence of Sound, and Glide Magazine.