The Rest is Missing: Swift's Satire on the Genealogy of Knowledge

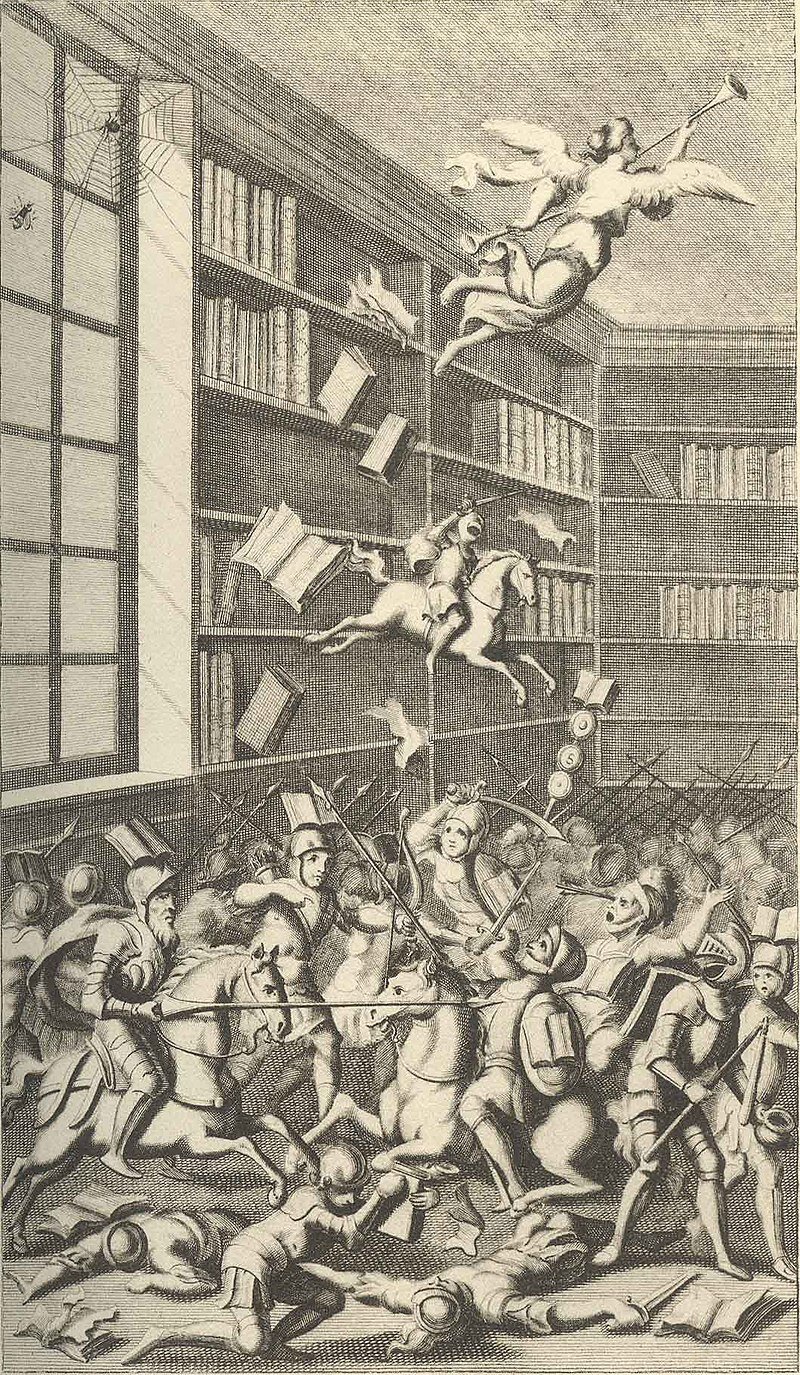

By at least 1704, Europe believed itself to be modern and, most agreed, modernity had not been achieved without a struggle. In that year, Jonathan Swift, the Anglo-Irish satirist best known for Gulliver’s Travels and “A Modest Proposal,” published The Battle of the Books (along with a longer satire called A Tale of a Tub), in which a violent war breaks out between books by ancient and modern writers in the King’s Library in St James’s Palace in London. Duodecimos of Descartes, Gassendi, and Hobbes launch an attack against tomes of Plato and Aristotle while one of the “Modern” poets implores “Godlike Pindar” to spare his life. Ink is spilt and torn pages cloud the air like canon smoke.

Jonathan Swift by Charles Jervas

Swift had written this short satire in response to a current print war about the relative merits of ancient authority and modern progress that began when Sir William Temple, Swift’s patron, had published An Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning in 1690 and William Wotton, a member of the Royal Society, countered with Reflections upon Ancient and Modern Learning in 1694. This debate, which gained steam into the early eighteenth century, was just the latest English iteration of the “quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns” (in French, querelle des Anciens et des Modernes) that reprised a similar controversy in the Académie Française of the seventeenth century. In brief, there were two sides to the querelle in England and France. The “Ancients” believed the classical Greeks and Romans were superior to all subsequent eras in learning, arts, and culture. From their perspective, modern achievement was, according to their metaphor, not much more than dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants.

The “Moderns,” on the other hand, believed current advances in all fields of study, especially the natural sciences, made it possible to surpass the achievements and learning of the ancient world. As Joseph M. Levine put it in his influential study The Battle of the Books: History and Literature in the Augustan Age (1991), the “ground had been well-prepared” since “for centuries an argument had been drawing gradually to a head between the rival claims of the ancients and moderns,” until suddenly, with the publication of Sir William Temple’s essay, “it looked almost as if the fate of Western civilization hung in the balance: whether to go forward to something new and better, an advancement of learning and a material culture beyond anything hitherto known, or whether to continue to hanker after a golden age in the past and to lament the decadence of the modern world.”

Woodcut from The Battle of the Books

The stakes of this particular episode were high. And as comically topical as Swift’s “Battel” was (the title page indicates that the battle had been “fought last Friday”), it captures the degree to which the passage to modernity was being imagined in the early modern period and the Enlightenment not as a neat, linear progression in which the intellectual inheritance of the past was passed down as a treasured and intact heirloom from one generation of thinkers to the next, but as an antagonistic confusion where the relationship between past and present was far from clear.

The “Modern” position was founded upon a kind of genealogical anxiety, a sense that history is like a game of telephone, in which the more the secret word is whispered from person to person, the more it becomes distorted, misunderstood, or falsified. To adopt the “Ancient” position of imitation is to risk committing oneself to a tradition and way of thinking that might, upon closer scrutiny, prove itself to be false, misleading, or arbitrary.

And historical forgery was exactly what was at stake in the Swift/Temple/Wotton episode. After Temple and Wotton had published their rival essays, the next phase of the argument became a debate over the epistles of Phalaris, a tyrant of Acragas in Sicily from the sixth century BC. Temple’s work had praised the letters of Phalaris, and as a result the Dean of Christ Church at Oxford commissioned Charles Boyle, who was an undergraduate at the time and would become the fourth earl of Orrery, to publish a new translation of the letters. Wotton and Richard Bentley, a prodigious classical philologist, knew it was a forgery and saw their opportunity to pounce on Temple and Christ Church’s “ludicrous error”: Bentley’s “Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris” was published in the second edition of Wotton’s Reflections in 1697, a scholarly “tour de force” that demonstrated how important modern philology was, since Temple and Boyle’s “indiscriminate worship of antiquity” could lead only to “error and frivolity.”

The flurry of competing publications didn’t stop there. Eventually, Swift entered the fray with A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books. Swift, though he numbered among the Ancients, explores this anxiety about forged history, sometimes satirically, sometimes seriously. For instance, The Battle of the Books is framed as an incomplete manuscript with mock scholarly annotations in Latin. Sections of the “manuscript” are missing, and most importantly the ending of the piece—the outcome of the literary skirmish—remains unknown. Desunt caetera, the rest is missing, it reads.

It’s hardly surprising, given the anxieties about history and the relationship between past and present this episode in the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns exposed, that faked historical artifacts become something of an obsession throughout the rest of the century into the nineteenth: Horace Walpole claiming to have found a medieval manuscript that served as the basis for his bestselling gothic story The Castle of Otranto (1764), the controversy over the authenticity of James Macpherson’s “translations” of the ancient Gaelic poetry by Ossian, and even the popularity for fake medieval ruins—“follies”—in landscape design.

Earlier in Swift’s piece, it becomes more clear that what is at stake is not a war between opposed factions but a convoluted, perhaps unclear, lineage from the past to the present, as when Dryden and Virgil face each other in combat: “Dryden, in a long harangue, soothed up the good Ancient; called him father, and, by a large deduction of genealogies, made it plainly appear that they were nearly related.” Presumably, it has taken the painstaking (some would say pedantic) work of modern philological practices, as pioneered by the likes of Moderns like Bentley, to show with a “large deduction of genealogies” that there is a connection between ancient and modern poets.

Swift’s image of intellectual chaos resembles the end of Alexander Pope’s Dunciad, his mock-heroic poem about how the Goddess “Dulness” presides over an age of cultural and artistic decay, which closes with a famous image of anti-Enlightenment:

Art after Art goes out, and all is Night.

See sculking Truth in her old cavern lye,

Secur’d by mountains of heap’d casuistry:

Philosophy, that touch’d the Heavens before,

Shrinks to her hidden cause, and is no more:

See Physic beg the Stagyrite’s defence!

See Metaphysic call for aid on Sence!

See Mystery to Mathematicks fly!

In vain! They gaze, giddy, rave, and die.

Thy hand great Dulness! lets the curtain fall,

And universal Darkness covers all.

We tend to think of the Enlightenment as a time of epistemological certainty. Eighteenth-century thinkers like Descartes, Locke, Hobbes, and Hume rejected the past—especially the medieval and Scholastic tradition—because they were certain of their own modern methods and innovations. I think we perhaps underestimate the degree to which this confidence in their own abilities was born of necessity in light of their doubts about how the past had led them to the present. What if a venerable authority of the past had actually been passed down to us in the present as a series of blunders or misinterpretations? Sure, they didn’t think too highly of the medieval intellectual tradition, as when Swift writes, “The rest was a confused multitude, led by Scotus, Aquinas, and Bellarmine; of mighty bulk and stature, but without either arms, courage, or discipline.” But this description of medieval thinkers as “a confused multitude” is equally a description they would have applied to themselves and their knowledge of the past. The Enlightenment may have coined the phrase “Dark Ages” for the medieval period, but it was also true that they themselves were increasingly aware of the degree to which they were in the dark about the very past they had come from.