Three Genealogies: An Allegory

Alessandro’s Magnasco’s Satire on a Nobleman in Misery (Detroit Institute of Arts)

In the center of the painting reclines a nobleman. He holds in his hands the two sources of his nobility, his sword and his family’s genealogical tree. The lordly man, however, is impoverished. Though still wearing aristocratic garb, his attire is tattered and patched. There are no attendants to share his feast of garlic and onions.

A rusty helmet rests unused, as useless as its owner. In the background is his wife, tending the fire, reduced to scullery work. Behind the nobleman, a spectral figure points and mocks. He makes a gesture of cuckold’s horns above the nobleman.

Alessandro’s Magnasco’s Satire on a Nobleman in Misery (1719-1725) portrays the reduction of the nobility in the Modern era. The patrician is pathetic. He alone takes his genealogy seriously. Viewers are supposed to laugh at the wasted pretensions of the past. However, despite our snickering, this forgotten man is the emotional heart of the painting. The genealogy he clings to is more central than the mocking presence behind him and his sword is still at hand. The mocked nobleman remains the hero of the painting.

Allow me to propose an anachronistic and allegorical reading of the painting. Contemporary genealogical discourses tend to take three possible forms, symbolized in this painting: Nietzschean/Foucauldian, Christian, and Modern. (For a more thorough description of these modes of intellectual history, I recommend Alasdair MacIntyre’s Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry: Encyclopedia, Genealogy, and Tradition. MacIntyre’s modes have influenced my reading of this painting.) Let’s begin by attending to the first two forms. Both of these genealogical types are deeply interested in change, historicity, contingency across time, and the origins of different episteme. However, for Foucault and Nietzsche, contingency goes all the way down; there are no deeper stories. As Foucault writes, “nothing is fundamental. . . . There are only reciprocal relations, and the perpetual gaps between intentions in relation to one another.” William Connolly describes the genealogical task as exploring “a deep contingency, a lack of necessity in things, a background of emptiness.” There is nothing deeper than the contingencies of the will to power.

In contrast, Christian genealogists (like Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, Catherine Pickstock, and, well, me) see deeper stories that run through contingency because Providential Love is still at play in temporality. God creates the difference between the eternal and the temporal. Nietzschean/Foucauldian genealogists supposedly are philosophers of difference but in fact seek to deny ontological difference by denying the difference between Creator and creation. In so doing, they fall back into a monism either in the form of Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence and amor fati, Foucault’s denial of anything besides will to power, or Deleuze’s univocity. Temporality was discovered by the original Christian genealogist, Augustine, precisely because of his insistence on the Creator-creature difference as the source of temporality and contingency. The task of the Christian genealogist is “to apprehend the point of intersection of the timeless with time.” We seek to articulate Christian tradition in a way that speaks to our times. Christian genealogists know the importance of history considering God’s creation of time and His entrance into time through the Incarnation, the pilgrim church, and the activity of the Holy Spirit.

In my allegorical reading, the mocking figure is one who uncovers pretense, exposes contingency, and identifies will to power even in the defeated. He is a type for the Nietzschean/Foucauldian genealogist. The nobleman’s genealogy lacks validity; its origin does not lie in some fundamental reality but in the sword. The mocking figure succeeds in showing the contingency of any epistemic power structure. The knowledge claims of a noble genealogy are expressive of an episteme that has passed and lacks the power to assert itself again; its values have been transvalued. This is the dissolving mockery of the genealogist.

And yet, the genealogist remains ephemeral. He lacks the solidity of the nobleman, providing only dissolution without continuity.

The nobleman represents something real even if he has been eclipsed. His genealogy is grounded in a continuing tradition and so was earned by the sword and by service. A family tree is a real thing, linking people across time, providing the continuity upon which human community depends. However, for a Christian genealogist, the danger of the nobleman is the paradox of nostalgic triumphalism. We can be tempted to locate a historical moment as the heart of history and a triumph of Christendom. The realness of the nobleman’s genealogy can be overstated, forgetting bastard lineages and questionable origins. And that sword was not likely only lifted in just causes. The Christian genealogist can be too attached to an era and can succumb to narratives of decline. Tempted by mere temporality, we situate ourselves in a particular time too deeply. Our story becomes a nostalgic reenactment of the temporal, thereby forgetting the timeless.

What of the third form of genealogy? The third form is expressed not within the painting but from the position of the viewer. Specifically, it is that of the Modern or Enlightened perspective. The painting was a satire for the ascendant class in the eighteenth century. They are the victors of the painting, wealthy enough in the Modern era to laugh at both figures. “Enlightened” Moderns situate themselves outside of the frame. Cyril O’Regan in Anatomy of Misremembering writes:

The secret of the Enlightenment is that as it provides the language of critique, it effectively immunizes itself from criticism . . . Anti-Enlightenment counterproposals are excluded from the arena of argument on the formal grounds of anachronism: belonging essentially to a previous (and . . . superseded) period.

Nietzschean/Foucauldian genealogists—and, to a lesser extent, Christian genealogists—have impacted the academy, but they remain within Modernity’s frame. Enlightened Moderns situate themselves outside of the frame of discourse by claiming to provide the neutral and progressive frame of all “rational” discourse. This framing takes its position for granted, constantly reaffirming itself “since the only game in which it is willing to participate is one in which it is a player, referee, and rules committee.” In light of the hegemony of progressive Enlightenment, the nobleman is cast as miserable and the Nietzschean/Foucauldian as the jester.

For a Christian genealogist, the painting is dispiriting. Framed by Modernity, we are irrelevant to the Modern, which situates itself beyond our critique. We are faced with a danger of perpetually holding up a genealogy that is dusty and unconvincing. Our arguments cannot get off the ground because the Modern denies the grounds of our arguments. Further, the Christian position appears unconvincing precisely because we are so diminished compared with our noble past. The nobleman’s claim to cultural importance is undermined by his diminishing status and by the wealth and power of those looking at this painting.

What then to do? First, the task of the Christian genealogist is to bear in mind the mocking voice of Foucault and Nietzsche while also showing how the stories we tell are deeper than the Nietzschean/Foucauldian. But more importantly, we must show how our stories transcend the frame of Modernity. To understand our fundamental task, let’s look at our painting again. First, we must restore our attention to the woman in the background.

Presumably, she too feels the sting of being diminished. Amidst these ruins, she tends the fire. She continues the simple work of the household. The work of a Christian genealogist should serve the broader household of the church. We work to tend the Fire that pre-ignites our own service. Our work is contingency in service of the Necessary, temporality in service of the Eternal.

Let us return to the nobleman again. He has been impoverished by forces beyond his control. But he presents us with a challenge. Can we see in poverty our deliverance?

Jesus teaches, “Blessed are you who are poor, for the kingdom of God is yours.” The nobleman may be more noble in his poverty. Western Christianity is reluctantly rediscovering the poverty of worldly denial. Our hope is that this is grounded in the world’s denial of Christ. Here we find an important genealogy, a visual precursor, to Magnasco’s satire; his painting is a riff on paintings of the mocking of Jesus.

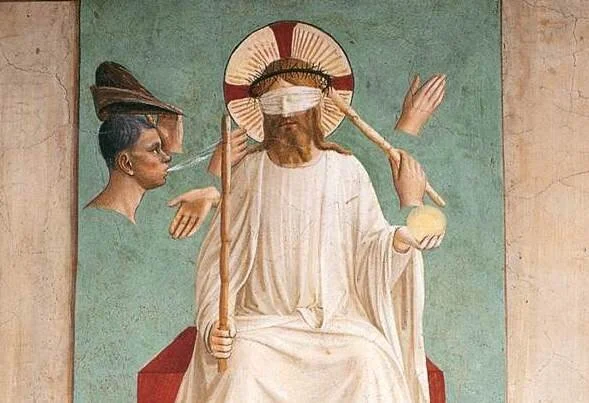

Fra Angelico’s Mocking of Christ, 1440

Jesus was poor, mocked, and diminished. He was captured by the dominant force of his time. He did not reject his impoverishment and so became our true wealth. From within Eternity, he so loved the World that he entered into our contingencies. We should always follow his path. If instead we cling to a triumphal genealogy or a genealogy of decline, we will forget that Christ’s Kingdom is not of this earth and that our true treasure lies in His sanctifying poverty.

Further, we must ask ourselves whose genealogy we hold dear. If it is a genealogy of our triumphs then it will be a genealogy of decline, one framed by the successful gaze of the Modern. But perhaps the nobleman holds another scroll with deeper stories written on it. The genealogy that matters is that of Providence, which, though inscrutable, is written in love.

The Jesse Tree in a Capuchin Bible, c. 1180

We ought then to hold to the genealogy of the tradition and scripture in one hand. In the other, let go of the sword and hold to the Cross. Our genealogies should serve the deeper story being written by Divine Providence. This might not end our diminishment, but it may turn our satirized status into a source of true renewal.