MacIntyre and Barfield on Remedies to the Catastrophe

In his 1988 Gifford lectures, Alasdair MacIntyre notes that “for us in our situation of radical disagreements a lecture can only be an episode in a narrative of conflicts.” I assume that many of us will have observed that the description of a “situation of radical disagreements” has only undergone intensifying timeliness in the thirty-five years since MacIntyre’s lecture. My modest purpose in this article is to bring MacIntyre into conversation with Owen Barfield. With the proviso that the method could be reversed to show how MacIntyre’s arguments could frequently support Barfield’s insights, I hope to offer a glimpse at how Barfield’s ideas anticipate and buttress MacIntyre’s gloomy diagnosis of the contemporary “incommensurability of rival fundamental moral, scientific, metaphysical, and theological standpoints,” and MacIntyre’s Aristotelian turn (to phronesis and “narrative identity”) in relation to Barfield’s more ambitious remedy of “poetic identity.”

At the beginning of After Virtue, MacIntyre makes the famously “disquieting suggestion” that a slow-motion cultural catastrophe has taken place “of such a kind that it has not been—except perhaps by a very few—recognized as a catastrophe.” This catastrophe has left us only with “simulacra of morality” because we have only “fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts of which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived.” One victim lost amidst the rubble is the “self,” which has become “a peg,” “nothing at all,” “in no way an actuality,” or “criterionless.” Thus Foucault, the paradigmatic modern genealogist, finds that the “self is dissolved to the point at which there is no longer a continuous genealogical project.” We must answer in the negative the questions that arise from this rather disquietening diagnosis: “Can the genealogical narrative find any place within itself for the genealogist? And can genealogy, as a systematic project, be made intelligible to the genealogist?”

MacIntyre’s proposed remedy for restoring “moral modes” to the self is to develop “a concept of self whose unity resides in the unity of a narrative which links birth to life to death as a narrative beginning to middle to end.” This has two requirements: that one be accountable to others and that one hold others to account. In the Gifford lectures, MacIntyre takes accountability to include, among other things, “a conception of a range of genres of utterance, dramatic, lyrical, historical, and the like, by reference to which utterances may be classified so that we may then proceed to identify their true sense.” MacIntyre claims in various places that the poetry of W. B. Yeats, Walter de la Mare, Marianne Moore, and others, is of philosophical interest, but assumes that Aquinas and Dante, say, were doing essentially the same sort of thing.

Barfield can be helpful here. First, he anticipated MacIntyre by demonstrating that the revolutionary upshot of late medieval and early renaissance intellectual culture was “the dissolution of unified enquiry into variety and heterogeneity” in which “the unity of enquiry . . . gradually becomes lost from view.” Consider “The Disappearing Trick,” a lecture of 1968, published two years later (and eleven years before After Virtue). Here Barfield notes that “a great deal of what is going on around us today can be traced to the presence in very many minds of an unspoken question and an unspoken answer to it.” The unspoken question: Do I exist? The unspoken answer: No, or I don’t know. Barfield, like MacIntyre, locates partial responsibility in behaviorist psychology and “popular and flourishing departments . . . of Sociology.” Barfield’s twofold remedy also anticipates MacIntyre: first, the cultivation of “intelligent reflection,” and second, nurturing the “modern concern with history” as “an existential encounter with the past'' because in that case “the rudderless and helplessly drifting ‘Do I exist?’ is converted into the very guarantee of our freedom and of our obligation to steer; we become, not the free Nothings of Sartrian Existentialism, but free spirits deep-rooted in the past, and responsible to it, growing thence towards the future and responsible for it.” This sounds, at the least, not incompatible with MacIntyre’s narrative identity and mutual accountability.

It also somewhat softens the diagnosis Barfield made decades earlier. Writing in 1927-28, the year Heidegger published Sein und Zeit, Barfield observed the intensifying modern experience of self-consciousness as “that which is cut off,” “what is left,” and “the paradoxical zero-point, where self-consciousness and nonentity coincide.” This relatively new feeling arose not merely because “the true Agnostic,” of which “the world is simply full,” finds “his mind full of a queer mixture of odds and ends of scientific and religious theories.” Such minds tend to picture “St. Thomas Aquinas grovelling in intellectual chains, while, say, Mr. H. G. Wells basks without effort in the sunshine of intellectual freedom.” Thus far, MacIntyre’s catastrophe; but, within it, Barfield locates a deeper level of alienation from language, and so reasoning, itself:

sooner or later, because words, too, have this sensual substratum, he begins to feel detached even from them. They are instruments which he picks up and uses and drops again. He begins to discover that, even when used in quite ordinary prosaic, logical forms, they can be made to prove the most contradictory things–can be made to prove almost anything. If he is a philosopher or a logician, he may develop his elaborate system of ‘antinomies’; but if he is a ‘plain man’, he will only become vaguely confused by the variety and disharmony of all the different systems of ideas (each apparently quite convincing when taken by itself), with which he is deluged from press, pulpit, and platform.

Barfield’s diagnosis of a deeper alienation from language induces a correspondingly more dramatic remedy. Time and again Barfield calls for total transformation of the individual—not merely the return to Aristotelian reasoning—as the properly scaled response to the catastrophe.

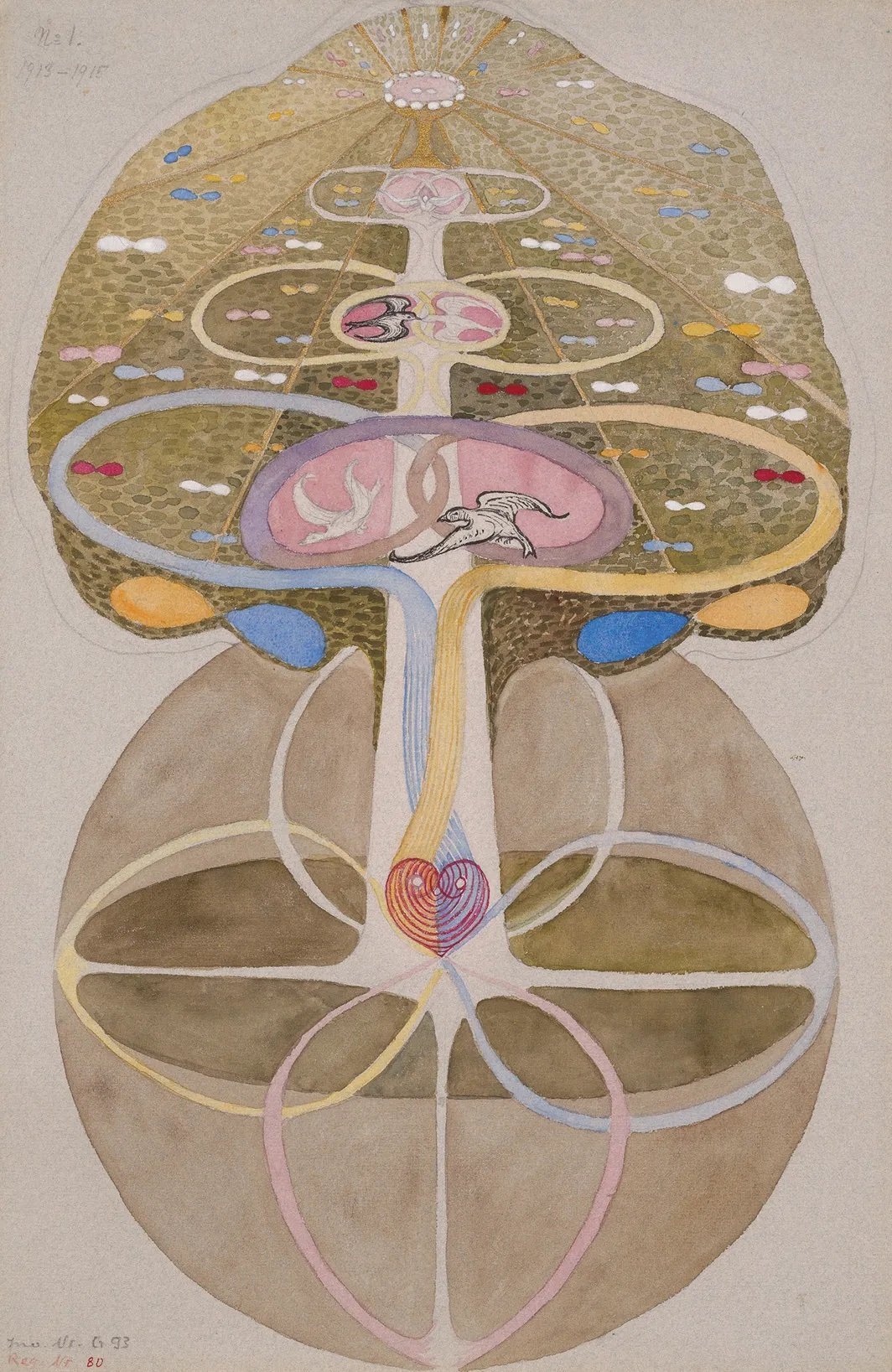

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No. 1

In his early work on poetic diction Barfield concluded that discursive reason can only analyze, but cannot produce, meaning: “the Logician . . . in his endeavor to keep [words] steady and thus fit them to his laws, is continually seeking to reduce their meaning. I say seeking to do so, because logic is essentially a compromise. He could only evolve a language, whose propositions would really obey the laws of thought by eliminating meaning altogether.” Barfield concurs with the Thomistic identity of thinking and being, but draws the paradoxical conclusion from it that the self has the structure of a synecdoche. After all, says Barfield, “in the background of the medieval mind”—including in its most sophisticated Thomistic and Dantean forms—is the logical identity of self and cosmos, microcosm and macrocosm, which is best expressed by metaphor and synecdoche.

Barfield found a resource to elaborate this view in Vladimir Solovyov. Solovyov’s task in The Meaning of Love was “the establishment of the relation . . . between part and whole in society. . . . Indeed it is a truism that civilization is threatening to break because of man’s failure to solve it.” Solovyov puts forward “the all-one idea” of an organic relation of parts to the whole in which the parts retain their individual identities while also having the identity of the whole. Barfield describes this as a mode of relation in which “not only man in general, but each individual man ‘may become all’ . . . Thus, in the ‘all-one idea’ realized, the part is the whole, not by merger, but on the contrary by intensive development of its true individuality or part-ness. Or rather the whole is the part; for, whereas when we think abstractly about being, as the in the processes of logic and classification, the whole is predicated of the part . . . in the actual process of being, the order is reverse, and the race or archetype is the species or individual—because it gives it being.”

An outline thus emerges of a notion of “poetic identity” to supplement MacIntyre’s proposal of “narrative identity.” MacIntyre roots the unity of the narrative self on its continuity across time, from birth to death; Barfield would conclude from this that the self at any given moment of its life is identical to the whole of it, to grasp which requires an act of imagination. So too, MacIntyre’s criteria of accountability to oneself and others enlarges from a model of rational explanation and critique to one of essential mutual identity: the basis of any rational exchange is the identity of being and knowing; metaphor and synecdoche are logical modes of that identity, in which every member of any group is both microcosm and macrocosm for the others. And this, “an ‘organic’ relation between part and whole,” is, Barfield says, “usually called love.”

Jeffrey Hipolito’s work has been published in The Oxford Handbook of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Journal of the History of Ideas, European Romantic Review, Journal of Inklings Studies, and elsewhere. His two forthcoming books about Owen Barfield will appear next year: Owen Barfield’s Poetry, Drama, and Fiction: Rider on Pegasus (Routledge, March 2024) and Owen Barfield’s Poetic Philosophy: Imagination and Meaning (Bloomsbury, April 2024).