Americans, Our Guns, and Catholic Social Teaching

This article is part of a series of responses to Episode 2.7 of the Genealogies of Modernity podcast.

In the episode “A Genealogy of American Gun Violence,” producer Christopher Nygren demonstrates how changes in technology have revolutionized the way that guns are used. Guns do more today than Stradano’s cannonballs did in the sixteenth century. Contemporary Americans need only turn on the news to be reminded of this. In tracing this genealogy, Nygren recounts different instances in history where societies have united to overcome gun violence. The looming question here is whether this can happen in today’s America.

In God Matters, Herbert McCabe argues there are two ways to talk about guns or two ways they carry meaning. Guns can be discussed at the level of physics—what they do as machines. For example, guns project bullets with a high level of force. We can also talk about guns in the context of human life. For example, guns are used to kill other animals. Gun talk thus inhabits two different worlds: the world of “percussions, explosions, rifling, and trajectories” and the world of “combat, marksmanship, self-defense, criminality, and so on.”

McCabe emphasizes that in human experience these are not two separate worlds: humans use physical objects within a particular context to communicate with one another. Today in America, guns are most commonly used in the following contexts: by cops to disable people who pose an active threat to themselves or others; by hunters to kill animals; by homeowners to defend themselves against intruders; by criminals to threaten the lives of others; and, at a horrifyingly common rate, by people intending to inflict violence on other human beings. Even in the diversity of these contexts, guns are used with the same effect: acquisition of total power over another.

Guns don’t just exist as pieces of machinery in American culture. Guns are now key chains, magnets, bumper stickers, and tattoos. In these forms, guns do not exist in the world of machines. Guns, in contexts divorced from a practical function, have come to bear a symbolic meaning. The symbolic meaning of guns in American culture arises from their common uses or functions. Guns in American culture have come to symbolize domination over others. The prevalence of guns, especially in these non-machine or symbolic forms, suggests that Americans have become obsessed with their symbolic meaning—dominating others. If Americans are going to be serious about reducing gun violence, I suggest we start dealing with our desire for domination.

One way to challenge this desire for domination is by getting comfortable with its opposite: dependence on others. Ultimately, this is the proposal of Catholic social teaching. Catholic social teaching challenges people to recognize their dependence on others in all social contexts by first asking who the poor and vulnerable are and how they are being affected. Then, it seeks to prioritize their voices in the life of the society.

So, who are the most vulnerable when it comes to gun violence in 2023 America?

Children.

Gun violence is the leading cause of death for children. According to a 2023 Pew Survey, the number of children and teens murdered by guns rose 50 percent between 2019 and 2021. These statistics, according to the same survey, are even more startling for communities of color who are affected by gun violence at disproportionately high rates.

Does the exhortation of Catholic social teaching to give attention to the lives of these children matter as gun violence against children continues to rise? Can the principle of the preferential option for the poor in Catholic social teaching amount to anything beyond the emptiness of “thoughts and prayers” that this episode criticizes?

Historically, it has. In Jephthah’s Daughter, Sarah’s Son: The Death of Children in Late Antiquity, Maria Doerfler demonstrates how moments of grief for the death of children historically have been occasions for people to re-think how they are living—or, as Doerfler puts it, for developing virtue. Meditating on the senselessness of the premature deaths of children, homilies, hymns, and prayers in late antiquity often led audience members to hope in the world to come: not to a fantastical or dismissive hope, but a hope that changed the way their audience understood the world they currently lived in. Their hope manifested in a new life—a new acceptance of the horrors of their current world and a new lived dependence on each other.

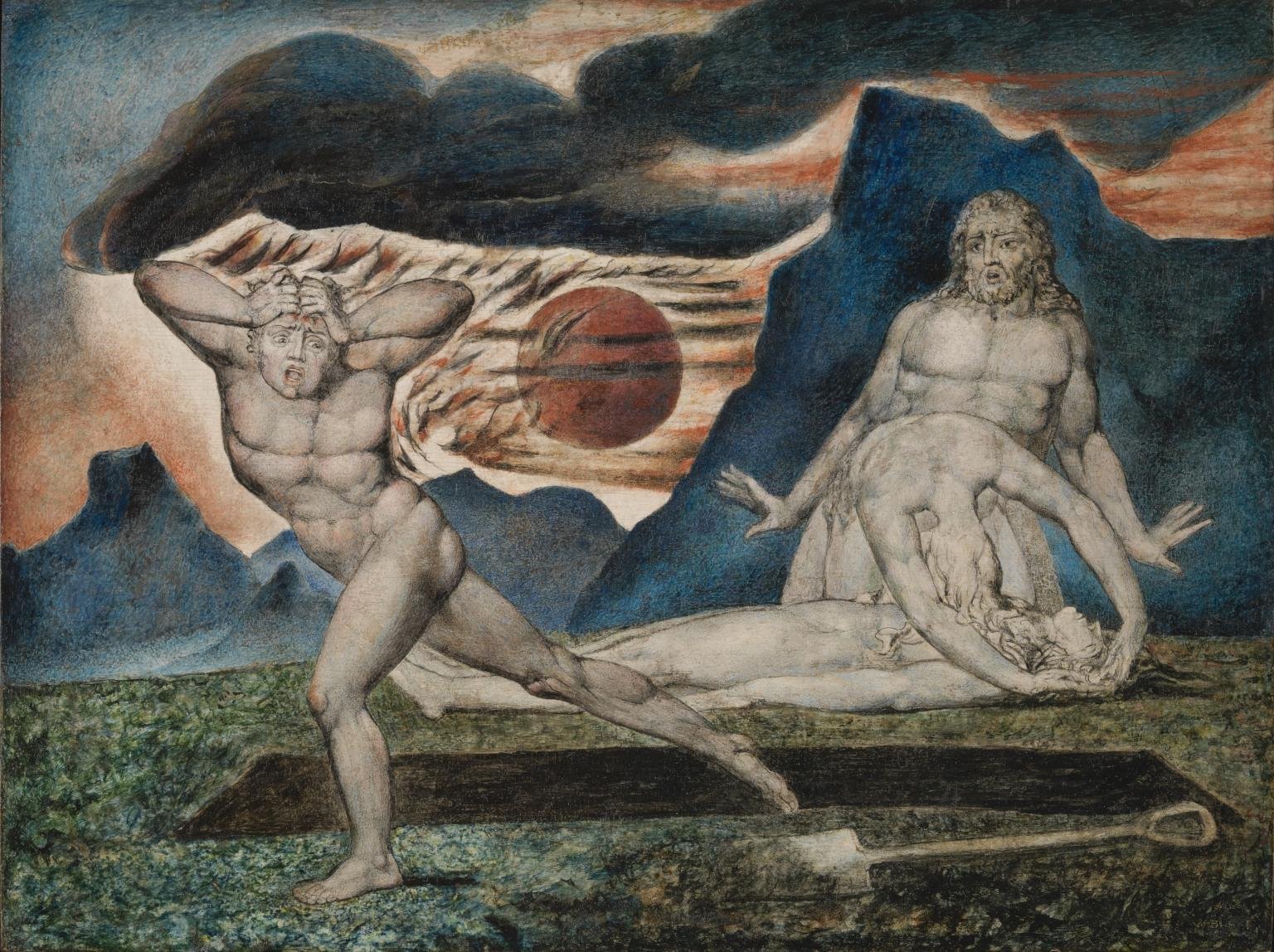

William Blake, The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, 1826

One example Doerfler discusses is the “dramatized homilies” about Eve’s grief for her son, Abel. Judith Kecskementi uses the term “dramatized homilies” to refer to a style of homilies during this period that added plausible details to enrich biblical stories. By including details about Eve’s grief, these homilists could connect Eve’s grief to their own experience of day-to-day violence. Given in a communal context, these homilies proclaimed the narrative that bereavement cannot be a solitary practice and these children’s lives were not inconsequential losses. According to Doerfler, these homilies expanded the arc of grief beyond a mother’s, or even a family’s, immediate horizon to that of the entire community.

The opening episode of this podcast series claims genealogies are about narrating the past so that we can flourish in the present and future. If this is true, the genealogy of gun violence cannot focus on the story of guns simply as machines. These machines exist in a human context—a world of “combat, marksmanship, self-defense, criminality, and so on”—where they carry meaning. In our world, Americans continue to use guns for domination.

As domination over other animals through gun violence continues to rise in America, so too does domination over the environment by infinite manipulation and exploitation for consumer use. There is domination over migrating populations by xenophobic policies that use vulnerable persons as political pawns, and also domination over the economy by business practices that maximize profit at the expense of human flourishing. If Americans want to reduce gun violence or have the “breakthrough” moment that this podcast episode describes other societies having, Americans must confront the effects of our domination. Americans ought to listen to the voices of those who are most vulnerable to gun violence. We must hear the silence that should be filled with the laughter of children whose lives have been taken. We must grieve for them. Telling the story of gun violence with attention to the attitudes and desires that have enabled guns to have the symbolic meaning they do today empowers us. It empowers us with the possibility of subverting the current world—a subversion much like the grief of the Christian communities of late antiquity for their children.

Catherine Yanko is currently a PhD Candidate at the Catholic University of America where she studies Moral Theology/Ethics. She is also an adjunct professor at Georgetown University. Her dissertation in progress is titled "Freedom and Self-Realization in the Thought of Josef Fuchs, Servais Pinckaers, and Herbert McCabe."