A Rejoinder to Irving

This entry is part of a series of responses to Theological Genealogies of Modernity, a special issue of Modern Theology edited by Darren Sarisky, Pui-Him Ip, and Austin Stevenson. In this installment, Darren Sarisky responds to Alex Irving’s reading of his “Neither Progress nor Regress: The Theological Substructure of T. F. Torrance’s Genealogy of Modern Theology.”

As my colleague Pui-Him Ip and I were planning the Theological Genealogies of Modernity conference, which took place in 2021, we wanted to shed light on certain basic issues regarding genealogies of modernity. As we used the term, theological genealogies of modernity refer to any complex, broad-sweep narrative account of the rise of a modern Western cultural order that highlights theology's role within that process. The Secular Age by Charles Taylor is probably the most well-known recent genealogical narrative of modernity. How can such narratives be assessed? What constitutes a proper starting point for evaluating narratives like this, or even for composing one? What sort of orientation is necessary to approach genealogies of modernity fruitfully?

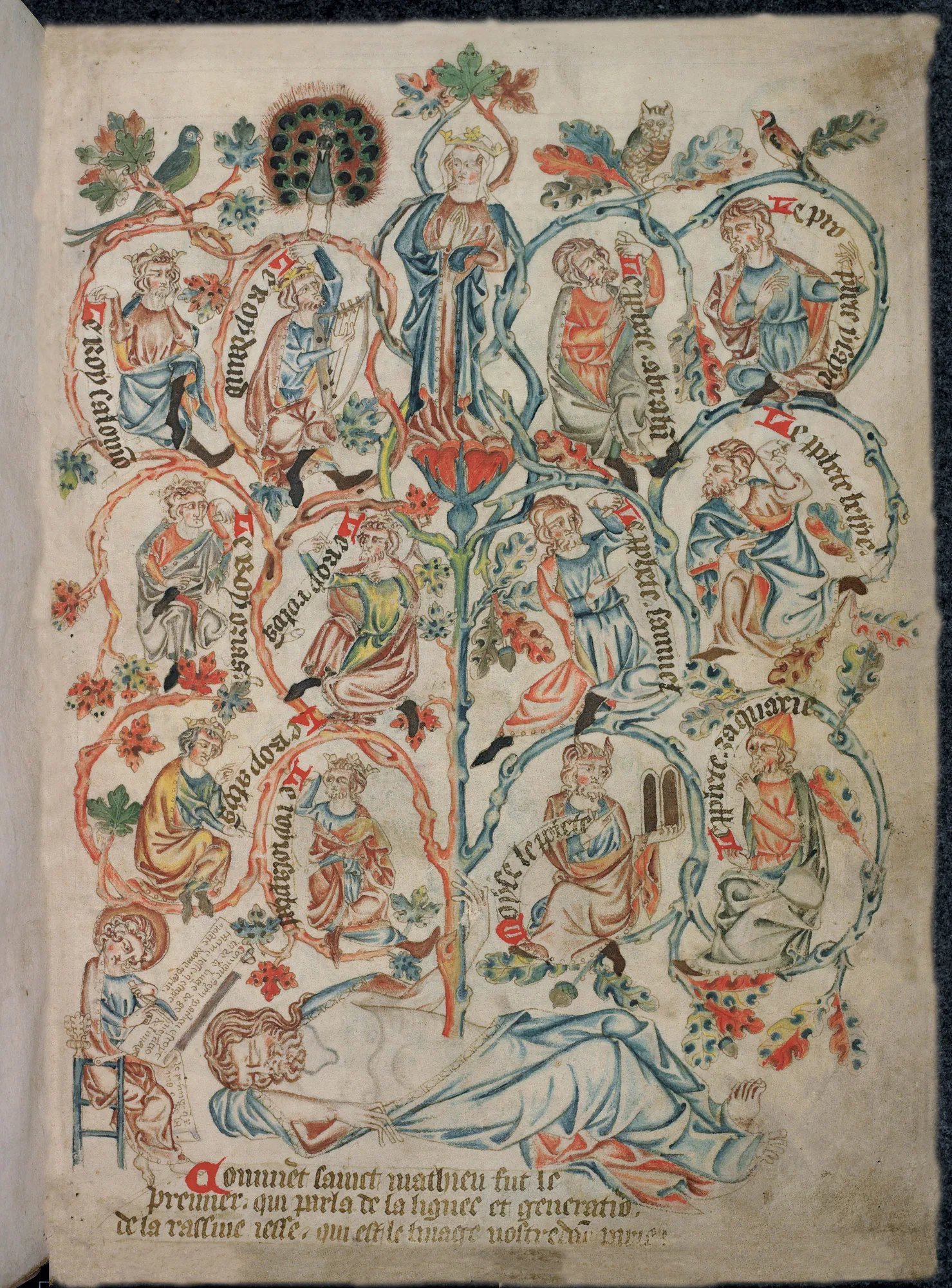

Tree of Jesse, Holkham Bible

This question brings me to Alex Irving’s response to my article on Thomas F. Torrance’s genealogy. Irving has fittingly focused on what my essay says about ultimate beliefs. He writes, “Sarisky’s article does more than just lay out the specifics of Torrance’s ‘ultimates’ as theological substructure. Sarisky goes on to show how this approach to theological apprehension lends shape to Torrance’s analysis of the theological interpretation of Scripture.” I would want to modify the second sentence slightly to make clear that what I am really after is to demonstrate how certain ultimate beliefs—essential theological commitments—structure all of Torrance’s genealogical reflections; I then turn to a genealogy of biblical interpretation to illustrate this. That said, Irving is certainly right to draw attention to the role of ultimate beliefs in my essay: they drive the genealogy, suggesting which topics are most important and also steering the treatment of these topics. As Torrance sees things, these ultimates are utterly necessary points of orientation for any genealogical work. If one does not start with them, problems will inevitably follow.

Allow me to provide one example of an ultimate belief that shapes Torrance’s genealogy. This will provide a taste of the full essay’s more systematic treatment of ultimates and their role in Torrance’s narrative. Torrance’s Christology shapes his understanding of time such that nostalgia does not drive his genealogy. As I write in the article,

Nostalgia has no place at all in Torrance's writings if it refers to a longing for a “past plenitude” from which the unfolding of time permanently separates people in the present. To feel nostalgia in this sense is a pitiful state: it represents an overwhelming desire for what definitively cannot be experienced, an intense attachment to what one cannot possess and enjoy any longer, because it is no longer present. Nostalgia could only obtain on the assumption that time is exclusively linear, marching relentlessly forward, never circling back in any sense to a significant moment; nostalgia also depends on the further assumption that contemporary people are therefore terminally estranged from their object of desire. It is thus a “distinctively modern phenomenon inasmuch as it acquiesces in the modern (historicist) view of time as a monochrome vector pointing toward the future, which renders the past as strictly passé, that is, as sheer inventory to be, perhaps, objectively known but most definitely incapable of signifying for (let alone transforming) us.” Torrance unambiguously rejects an exclusively linear notion of time. And with it, he disavows the second assumption associated with nostalgia, for only a strictly linear time could separate people from past texts and force them to read them from a distance. Torrance's genealogy does not so much privilege the past (or any temporal period, for that matter) as it focuses on the person of Jesus Christ. He reads biblical texts and the major theologians as pointing present-day readers to the God-man. Jesus’ parousia contains within it a past and a future coming.

Irving raises several other interesting issues in his response, such as how similar Torrance’s thinking is to Michel Foucault’s and Martin Heidegger’s. I acknowledge that these points deserve further discussion. But I will leave that for another time. Pausing over those issues would allow for a more nuanced understanding of both Torrance and the other figures. Yet this is not the time for delving into those details. I can only second the invitation with which Irving concludes, “To see the specifics of how Torrance’s ‘ultimates’ function as the theological substructure of his account of the development of theology, the reader will be best served by reading Sarisky’s article for themselves.” In addition to the one I have discussed here, there are several other specific ultimates to which Torrance is committed, each with its own influence on the genealogy, and each worth considering for its constructive function.

Darren Sarisky is a Senior Research Fellow at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Australia. His most recent book is Reading the Bible Theologically (Cambridge University Press, 2019).