Critical Theory and Ancient Political Philosophy

Part I: An Introduction to Critical Theory

As an increasing number of states begin to enact legislation limiting “critical race theory” in classrooms, popular discussion of the broader academic umbrella of “critical theory” has become more widespread. Many critics of this kind of legislation have pointed out the ambiguity surrounding precisely what critical theory—and specifically critical race theory—actually is. What we require, therefore, is a philosophical genealogy of this school of thought. While critics of critical theory correctly identify it with Marxism, a thorough genealogy reveals that important members of the Frankfurt School, the progenitors of critical theory, saw themselves as more than the heirs to Karl Marx. Attending to the work of Max Horkheimer, one of the Frankfurt School’s most important but least recognized members, it is clear that they understood themselves to be the true heirs to Socrates, and thus the true continuers of the tradition of political philosophy initiated by the ancients. This self-understanding is, however, seemingly based upon a serious misunderstanding of the ancients’ project, and its subsequent confusion with the project of the Enlightenment. A thorough analysis of Horkheimer’s supposed genealogical connection to the ancients will help proponents of critical theory clarify where they stand in relation to the rest of western philosophy. Critics of critical theory will also benefit, since a genealogical analysis will help to clarify precisely what it is they are criticizing.

Strictly speaking, critical theory is a philosophical approach pioneered by members of the Institut für Sozialforschung (University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research) during the middle of the twentieth century, a group popularly known as “The Frankfurt School.” At the outbreak of the Second World War, the Frankfurt School migrated to the United States, and many of its members became influential in the American academy. Chief among these intellectuals (at least in terms of influence) was Herbert Marcuse, mentor of radical political figures like Angela Davis and godfather of the “Port Huron Statement,” a kind of manifesto for the emerging “New Left.” Consequently, the intellectual roots of the Frankfurt School are often overlooked in favor of a focus on the radical political action that its members inspired.

While it is true that all members of the Frankfurt School were avowed disciples of Karl Marx, scholars often overlook the nuanced ways in which the School’s “critical theory” of philosophy innovated upon and departed from traditional Marxist thought. Actual engagement with the writings of the early critical theorists reveal the heterodoxy of the Frankfurt School’s Marxism. Figures like Marcuse and his contemporaries Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer wove Freudian psychology together with observations about the effects of industrialization in an attempt to explain the lack of the proletariat revolution predicted by orthodox Marxist thought. The incorporation of Freudian psychology into broadly Marxist thought is generally presumed to be the greatest innovation made by the Frankfurt School. Indeed, this is what allowed for one of their most famous theses: that the social structure of modern liberal democratic societies create psychological barriers which prevent the oppressed working class from seizing the means of production. This incorporation of Freud allowed the Frankfurt School to explain the lack of a proletariat revolution by referring to the constraining influence exercised by social “structures” and “institutions” which prevented them from developing “consciousness” of their situation. Indeed, the terms “structural” or “institutional” racism, which are undoubtedly familiar to anyone involved in contemporary American political discourse, emerge directly from the Frankfurt School’s discussions of these matters.

Critical theory proposes to solve the problems caused by social structures and institutions by subjecting them to ruthless philosophical criticism. The connection to Marx is here perhaps most evident, as it echoes Marx’s own insistence on a need to develop a “ruthless criticism of everything existing” in order to speed along the inevitable proletariat revolution. For critical theorists, the preeminent task of philosophy is to examine the various power structures existing in society and point out their philosophical incongruities for the sake of social progress. While the identification and analysis of social structures and institutions is certainly attributable to the incorporation of Freudian psychology, the basic idea of using philosophy to critique the existing political order is to be found—at least according to Horkheimer’s “The Social Function of Philosophy”—at the very foundations of philosophy itself.

An analysis of “The Social Function of Philosophy” will help to clarify the genealogical connections Horkheimer found between critical theory and ancient philosophy. At the same time, it will also reveal Horkheimer’s fundamental misunderstanding of the ancients, and his connection to the ideals of the Enlightenment. Horkheimer begins “The Social Function of Philosophy” by noting that, unlike the “hard” sciences, philosophy’s place in the existing social order is far from clear. Hard sciences, Horkheimer observes, tend to reinforce the social structures of the prevailing order. Indeed, in many ways, the hard sciences are defined by this reinforcement. The aims of physics or chemistry, for example, are dictated by the needs created by the structure of a given political regime. As such, the products of a science always serve to strengthen and reinforce the existing structure of political community which dictates how that science is practiced.

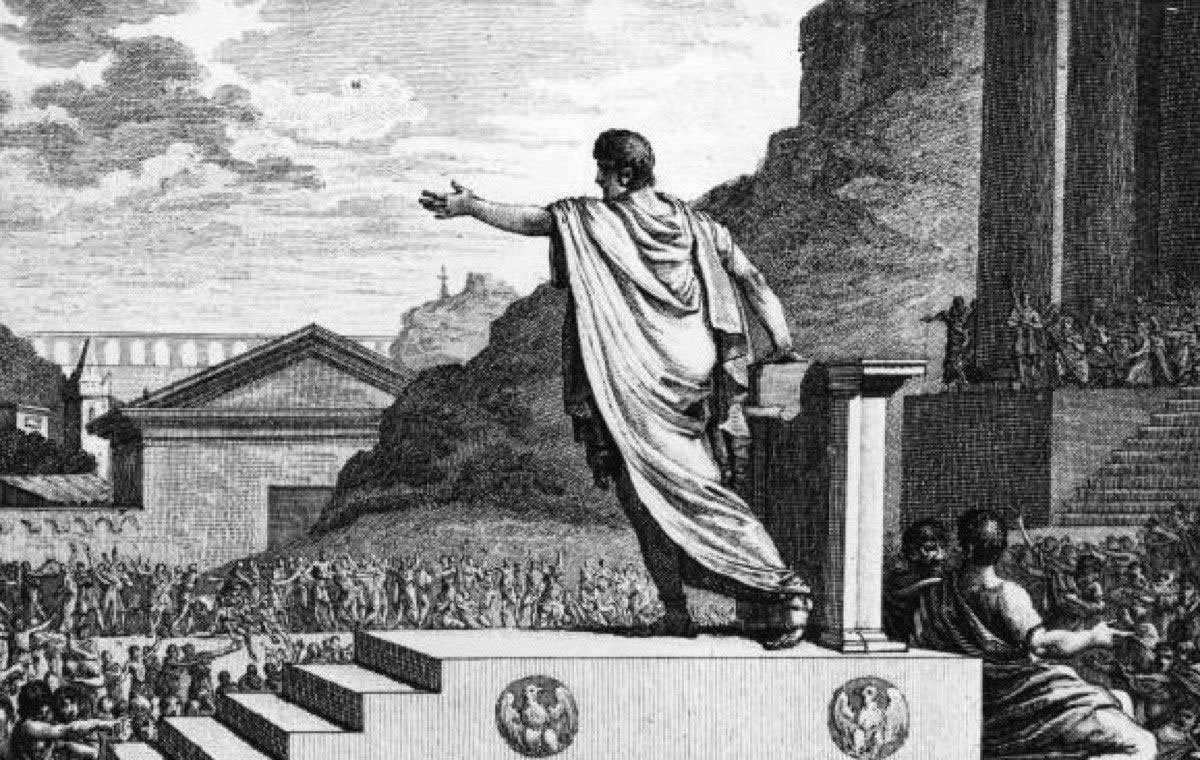

Philosophy, by contrast, is defined not by its conformity to and affirmation of the existing social order, but rather by its intense opposition to it. Philosophy, according to Horkheimer, has exhibited a “strained relationship with reality as it is,” especially its expression in their own political communities, “ever since the trial of Socrates.” This tension arises, Horkheimer claims, as a result of the basic philosophic principle that “the actions and aims of man must not be the product of blind necessity.” Thus, the philosopher is presented as a kind of extreme skeptic, whose task is to cast “the light of consciousness even upon those human relations and modes of reaction which have become so deeply rooted that they seem natural, immutable, and eternal.”

Horkheimer contends that such an iconoclastic approach to the existing order is necessary, at least in the present age, because of the growth of a kind of mechanistic rationalism which stems from the symbiotic relationship between the existing social order and the hard sciences. Faced with the behemoth of industrial society, authors who would style themselves philosophers attempt to “sell” something resembling philosophy to the masses by presenting it as something like a hard science. “Philosophy” is thus framed as a discipline useful to the prevailing social order, rather than critical of it. Consequently, philosophy is subordinated to the tasks and desires of the prevailing order. This subordinated “philosophy” does nothing more than affirm the existing order. This process implicitly relegates any sort of question about the enduring suitability of that order to the realm of “subjective evaluation by the individual who has surrendered his taste and temper” to the present structure of society. It is only through the practice of an explicitly critical philosophy that a wholly stagnant self-affirming social order can be avoided.

At its roots, then, critical theory was developed as a tool to counter the repressive and potentially destructive forces of modern industrial society, which seeks to subordinate all reason to itself. In many ways critical theory concerns itself with a moral critique of the existing order, pushing society to strive toward what practitioners of this philosophical method believe to be greater heights of human progress. Critical theory understands itself to be a means of freeing philosophy, and thus the life of the mind from the homogenizing influence of the existing order. Max Horkheimer develops this argument in “The Social Function of Philosophy,” where he draws direct parallels between his critical theory and Socratic philosophy. In the next installment in this series, I will explore whether Horkheimer has legitimate grounds for this comparison—or whether his identification of critical theory with the political philosophy of the ancients might misrepresent both his own theory and theirs.

Joseph Karol Natali is a third year PhD. student in the political science program at Baylor University. His research focuses on American Institutions with a secondary focus on the impact of 19th and 20th century German existentialism on contemporary political theory.