Gaining the Eternal

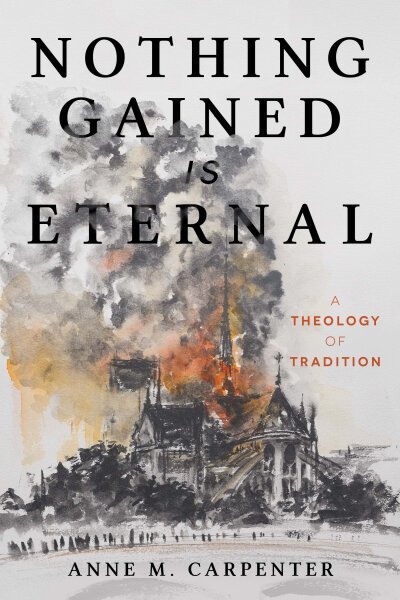

When the roof of Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire in 2019 and the image of its spire engulfed in flames skittered across our screens, there rose a great plume of interpretation. Take-havers everywhere, it seemed, scrambled to proffer competing theses for which this cataclysm must certainly be a metaphor. Beneath these think-piece pronouncements, I noticed a deeper response—a sinking, impotent dread: the terrible realization that something surviving to us across the centuries can die, can be lost for good. Anne M. Carpenter’s Nothing Gained Is Eternal: A Theology of Tradition (the cover of which is bedecked in an arresting watercolor of the burning church) reveals the gestural character of all those post-conflagratory takes, but also the deeper naivete about being historical that kindles this dread in us. Nothing Gained takes its stand on the fact that history, and so tradition within it, is something to and for which we are—together and personally—responsible.

Like so many present imaginings of the Middle Ages, it turns out that our experience of the medieval Notre Dame was shaped by a nineteenth-century reconstruction. There was a twenty-year effort (initiated in part by the success of Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame) to undo an eighteenth-century “redecoration” in the French classical style of Louis Quatorze and then the desecrations of the revolutionary period. The spire destroyed in the 2019 fire was built as part of this endeavor. And the south rose window, one of three stained-glass masterpieces to survive the fire fairly unscathed, was rebuilt both during the eighteenth-century “redecoration” and then again during the nineteenth-century “restoration.” Indeed, while no definitive conclusions seem yet to have been drawn, it does seem that the 2019 fire that partially destroyed Notre Dame started as a result of a renewed effort to not only preserve, but also improve her. Just a little digging uncovers the truth that Notre Dame was not the immediate presence of France’s medieval Catholic heritage to its modern life, but instead was something mediated to us by a fraught and irregular historical process.

Nothing Gained Is Eternal asks how it is that the Christian past can be present here and now when it travels to us in the medium of a historical process not only fraught and irregular, but so often saturated with evil and sin. In this way, the book is, as its subtitle warns, decidedly a theology of tradition—specifically a Roman Catholic theology—setting out from the Second Vatican Council’s configuration of tradition as principally an operation by which faith’s deposit is “handed on” (tradere). Carpenter works out from there a speculative theory of precisely what that operation of handing on is. She calls the result a “metaphysic of tradition,” by which she means a theoretical heuristic that can shape and guide our inquiries into (as well as our debates about) the Christian tradition. It is an approach that aims to enrich the theology of tradition as a wider genre. But what really sets Nothing Gained apart is Carpenter’s simultaneous engagement with how the stability of any modern theological construction of tradition is threatened by the co-existence of the Christian tradition with Christian evil and sin—the sins of colonialism and racism in particular.

Nothing Gained is not only Catholic in its doctrinal starting point, but also its infrastructure. Carpenter frames her argument with four modern Roman Catholic thinkers of the late-19th and 20th century: Bernard Lonergan, Maurice Blondel, Charles Péguy, and Hans Urs von Balthasar. Since the moral and material vicissitudes of history trouble Christian tradition’s link of the past to the present, Carpenter begins by asking, with the help of Bernard Lonergan, “what is history?” History, to radically abbreviate Carpenter’s retrieval, is human action in its complete solidarity. This definition reveals why Carpenter selects colonialism and (especially) race to specify the problem of sin in tradition: race “cleav[es] apart the solidarity by which human beings are, the solidarity by which God in Christ brings us to participate in the divine nature.” Moreover, “modern race is a Christian invention, and Christians are,” because history and tradition are theorized here as human action, therefore “responsible for their history and their tradition.”

Here, we are led to ask what tradition is such that the history of colonialism and race can afflict it thus. On this point Carpenter integrates the French Catholic philosopher Maurice Blondel. Drawing especially on Blondel’s influential essay, “History and Dogma,” Carpenter answers that tradition is that human action which mediates unconditioned truth and the contingency of historical process. This happens, for Blondel, not just in the passing on of information, but in human lives of action, specifically that part of living which he characterizes as the “literal practice” of religion. Carpenter re-introduces the problems of race and colonialism here by turning to the work of Black theologian Willie Jennings of Yale Divinity School. She deploys Jennings’ work to show how Christians have knit into the fabric of their action and religious practice a racial hierarchy and a colonial geography that interweaves unconditioned truth with contingent, malignant lies throughout a single history. Modern Christians, in other words, have for centuries been both caretakers and arsonists to their own cathedral of faith.

Blondel’s metaphysical phenomenology shows rather convincingly that tradition (and tradition’s action) effects this mediation between history and truth. But there remain practical, psychological, and existential questions of precisely how it does so, and also whether it can continue to do so under the real, sin-drenched circumstances of the colonial, racist history that in fact exists. To address this double problematic, Carpenter draws on the poetry of Blondel’s French contemporary, Charles Péguy. Péguy is probably best known to anglophone audiences for coining the term ressourcement, from which the French theological movement that, over against the regnant Neo-Scholasticism of the day, sought to return to ancient and medieval Christian sources took its name (and to which Nothing Gained is something of a cousin). Carpenter does readers the significant favor of retrieving that notion in correlation with another of Péguy’s major themes: “revolution.” Carpenter is at her most impressive in these passages, drawing out a theory of historical temporality from Péguy’s poetic ruminations on Joan of Arc, underlining how present action creates the junction of both the past-in-its-pastness and the divine charity of Christ with concrete living in its singular time and place. But it is the temporal function of Péguyiste “revolution” that proves crucial, casting light on the constant gift and challenge of “beginning again” which renders a “second innocence” possible after we have ineluctably squandered the first. Carpenter makes clear that ressourcement without revolution risks reinscribing the lies of the past, and revolution without ressourcement risks the forgetfulness that would set all clocks to midnight and all calendars to Year Zero.

After building up the foundations of her argument through Lonergan, Blondel, and Péguy, Carpenter finally introduces the theo-dramatic theory of Hans Urs von Balthasar (about whom Carpenter wrote her first book, Theo-Poetics: Hans Urs von Balthasar and the Risk of Art and Being) as a capstone. If drama concerns the meaningfulness (or absurdity) of human action through time, then “theo-drama” concerns the ultimate meaningfulness of human action in its cooperation with God through time. The saints struggle through the absurdity of flat tropes or genre conventions—and through the absurdity of human action writ large—to live as themselves in the way God knows and loves them. Carpenter invites us to see that tradition mediates the history constituted by human action with the ultimate truth of that action hidden in God. Moreover, it accomplishes this mediation at the site of each person not in isolation, but in radical solidarity with every other. Carpenter’s account becomes a properly theological metaphysic when she insists that this solidarity has its principle in the person of the crucified and resurrected Son of God, the Lord Jesus Christ.

In every chapter of Nothing Gained, a Black intellectual voice breaks through the symmetries of speculative construction to raise the challenge of colonialism and race. In this last case, it is James Baldwin, who helps fund a radical, but surprisingly congruous reconfiguration of Balthasar’s treatment of the saints. Carpenter highlights Baldwin’s claim that alienating Black folks from their own selfhood is our racist culture’s principal consequence. She argues that after the establishment of racial hierarchy, the Black subject is—in Balthasar’s technical sense of the word—the paradigmatic saint. Against the “roles” in which colonialist and racist action cast them, they insist on being-themselves as God knows and loves them to be. To the extent they can live into Baldwin’s claim that Black folks will not be free from racism until white people are (and so Black anti-racism requires love for white folks), Carpenter thinks Black subjects make Christian kenosis visible in and to our tradition.

The restoration of Notre Dame de Paris after the 2019 fire has been controversial. Some reacted negatively to how the cleaning process scrubbed away patina from the walls, leaving the stone brighter than in living memory. There has been debate about spire design and about the inclusion of contemporary art in plans for future decoration. Nearly a thousand mature trees—hundreds of years old—have been cut down for the needed lumber. Before construction scaffolding could be erected, forgotten tombs were unearthed that needed investigating. The path to a renewed wholeness for the great cathedral remains fraught, irregular. Similarly, Carpenter acknowledges that the theological metaphysic of tradition in Nothing Gained will prove controversial, in need of revision, reconsideration, expansion, and augmentation. It is, on Lonergan’s account, like every metaphysic: a heuristic, a way of anticipating what we will need to guide our thinking-together. But it is also, as Blondel reminds us, a metaphysic which is only real to the extent that it is put into action.

Jonathan Heaps, PhD, is a Lonergan Fellow with The Lonergan Institute at Boston College. His first book, “The Ambiguity of Being: Bernard Lonergan and the Problems of the Supernatural” is forthcoming from The Catholic University of America Press. He lives in Austin, TX.